ABOUT BROOKINGS

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Copyright 2012

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

www.brookings.edu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data

Gormley, William T., 1950

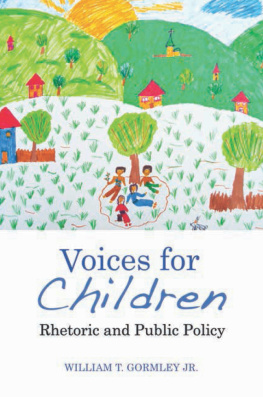

Voices for children : rhetoric and public policy / William T. Gormley Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Focuses on why children's issues and programs have been given less attention and monies compared to those for the elderly with emphasis on how the mass media have covered children's issues and how this has influenced public opinion and, in turn, lawmakersProvided by the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-8157-2402-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Child welfareUnited States. 2. ChildrenUnited StatesSocial conditions. 3. ChildrenServices forUnited States. I. Title.

HV741.G645 2012

362.70973dc23

2012028178

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed on acid-free paper

Typeset in Sabon

Composition by Cynthia Stock

Silver Spring, Maryland

Printed by R. R. Donnelley

Harrisonburg, Virginia

Acknowledgments

T his book originated because I believe that we must improve the quality of public discourse about children and public policy. Based on a growing body of literature, issue frames seem to be particularly important. But we lack hard evidence on which issue frames advocates prefer, how this has changed over time, and which issue frames appeal to the general public and political elites. I sought to obtain that evidence and to weave it into a broader narrative about political persuasion.

My focus on children's issues is not accidental. For two decades I have devoted much of my own research agenda to our youngest citizens, whom we claim to love but who nevertheless often get short shrift when public policy is made. They deserve better public policies and a better future.

While writing this book, I benefited enormously from many people who offered advice, criticism, and support.

I would like to thank my colleagues at Georgetown University and especially the Georgetown Public Policy Institute for many intellectual contributions. I owe a special debt to Jon Ladd for helping me to think through the logistics of some issue-framing experiments, to Shay Bilchik, who helped me to understand child welfare and juvenile justice issues, and to E. J. Dionne, who did not always agree with me but who offered many opportunities to refine my arguments. Two faculty seminars at GPPI helped to sharpen my thinking.

I would like to thank Steve Wayne, Mark Rom, and Victor Cha for opening their classrooms to me for an issue-framing experiment that basically set this project in motion. I am also grateful to Dan Hopkins for very helpful comments and for recommending that I turn to Knowledge Networks for a vital second experiment. Stefan Subias at Knowledge Networks was accessible, resourceful, and responsive.

The Urban Institute kindly offered me an office for a year, so that I could concentrate on writing without interruption. Olivia Golden, Ajay Chaudry, Gina Adams, and others offered helpful criticisms and suggestions. At a critical juncture I also received excellent feedback from several faculty members at the University of Virginia's Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. My thanks to Eric Patashnik for arranging this visit.

As this book took shape, several excellent research assistants gathered, coded, and analyzed data. Kitt Wolfenden, Mark Hines, Anne Hyslop, Emily Page, Helen Cymrot, Shirley Adelstein, and Kim Dancy did great work and were indispensable to this project. I would like to extend a special thanks to Meg Loftus for converting my text into documents that looked like actual newspaper articles.

I benefited greatly from conversations with people who have thought deeply about child advocacy, issue framing, or the policymaking process, including Susan Bales, Emily Holcombe, Mary Fairchild, Megan Foreman, Beth Fuchs, Sarah Hammond, Ron Haskins, Jack Hoadley, Nina Owcharenko, Tim Smeeding, Kent Weaver, Jim Weill, Amy Wilkins, and of course my long-time coconspirator, Deborah Phillips. Tim Bartik and two anonymous readers gave the penultimate draft a careful reading, which helped me to integrate my arguments better.

I am grateful to fifty children's advocates affiliated with Voices for America's Children who agreed to in-depth interviews on their organization's issue priorities, strategies, and tactics. Their ideas contributed significantly to would not have been possible.

From the start, I thought that the Brookings Institution Press would be the perfect home for this book. I would like to thank Bob Faherty, director of the Press, for his early support; Janet Walker, managing editor, who oversaw the editing details with Diane Hammond, a meticulous copyeditor; and Larry Converse and Susan Woollen for their attention to the development of the cover, as well as the typesetting and printing.

Finally, I dedicate this book to the two women in my life: my wife, Rosie, and my daughter, Angela. At playgrounds, libraries, schools, and amusement parks (especially Harry Potter World) we have experienced the exhilarating joys of childhood together. Rosie and I want Angela to live in a world where these joys are within reach of every child.

CHAPTER ONE

Children:

Beloved but

Neglected

It must not for a moment be forgotten that the core of any social plan must be the child.

Franklin Roosevelt, 1935

T he condition of children in the United States is marked by a puzzling paradox: we view children very positively, but our public policies do not reflect that positive view. The federal government spends seven times as much on senior citizens as it does on children. Although state and local governments spend much more on children than on the elderly, all governments in the United States, combined, spend 2.4 times as much on the elderly as on children. Not surprisingly, given this considerable disparity, children are more likely than the elderly to be poor.

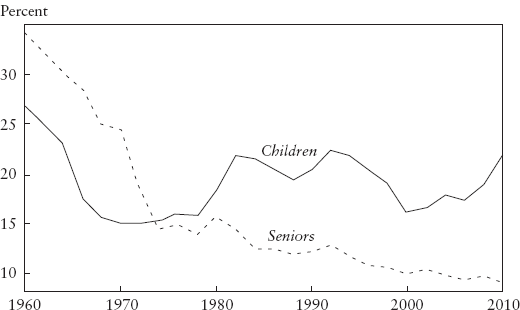

Poverty among senior citizens has declined dramatically since the 1960s, while poverty among children has not (

Figure 1-1. Poverty Rates for Children and Seniors, 19602010

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2011).

If we look beyond income to specific social conditions, the situation facing many children is distressing. One of every ten children suffers from asthma, approximately 14 percent of all students have one or more learning disabilities, one in four children lives in a household that runs out of food, and one in four children is raised by a single parentthe highest rate of any industrialized country.

These statistics are worrisome not only because of what they imply for conditions experienced by children today but also because of what they portend when these children become adults. Numerous studies show that, as adults, people's earnings, crime rate, health, and mortality are influenced profoundly by their experiences as children: children who are overweight or obese are more susceptible to type 2 diabetes, asthma, and other diseases; abused and neglected children are more likely to experience depression and suicidal thoughts and more likely to engage in crime and substance abuse; and low-birth-weight children have lower test scores, educational attainment, wages, and probability of being employed as of age thirty-three. Children who grow up poor face a wide variety of adverse effects; specifically, economic deprivation before age five is associated with lower earnings and fewer work hours three decades later.