Nostalgia and the post-war Labour Party

Nostalgia and the post-war Labour Party

Prisoners of the past

Richard Jobson

Manchester University Press

Copyright page

Copyright Richard Jobson 2018

The right of Richard Jobson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 1330 6 hardback

First published 2018

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services

Contents

Firstly, my thanks go to Hugh Pemberton and Mark Wickham-Jones. Their advice and insightful comments have been invaluable. I owe them both a tremendous debt of gratitude. As well as their excellent supervisory skills, they have been immeasurably supportive and helpful throughout the researching and writing of this book. I am also very grateful to David Thackeray and Richard Toye at the University of Exeter for their encouragement and support during the final writing stages. James Cronin and James Thompson provided some very good advice that enabled me to begin reworking and extending my research into a book suitable for publication.

There are a number of people who have discussed, commented on and displayed an interest in the contents of this book and whose opinions and expertise have been extremely welcome. As I am sure is usually the case, there have been too many discussions over coffee to mention. However, I would especially like to thank Clive Abbott, Dean Blackburn, David Drew, Nora Mulready, Luke Place and Reshima Sharma. I am also very appreciative of the way in which colleagues and students at the University of Bristol and the University of Oxford have helped to shape and refine my ideas.

The team at Manchester University Press have been very helpful throughout the publication process. I would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who commented on both my initial book proposal and the final draft. My gratitude goes to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for their funding during my studies: their financial contribution facilitated this research. Published material and excerpts from previous journal articles on the subject of Labour and nostalgia are reproduced in this book with the kind permission of British Politics , Contemporary British History , the Journal of Policy History and Renewal. In all previous publications, the suggestions made by peer reviewers have enabled me to develop my thoughts and arguments. I also want to thank the excellent assistance and expertise provided by archivists at the Churchill Archives Centre at the University of Cambridge, the Labour History Archive in Manchester, the archive at the London School of Economics, the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick and The National Archives in London (where I accessed the temporarily relocated Gaitskell Papers).

The initial conceptualisation of the central idea that informs this book was made away from the academic world and, because of this, I thank my friends and former colleagues amongst the weavers, warpers, dyers and finishers who worked at the textile mill in my village for their inspiration and encouragement. I hope that this work reflects the influence that they had on me at a particularly formative stage of my life.

Finally, I would like to thank my family. This book has only been made possible by their support throughout the years.

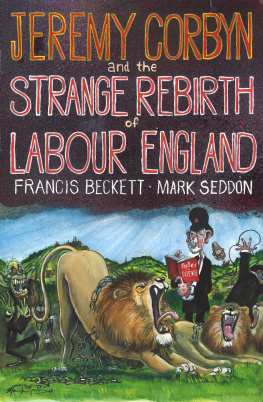

Having secured a decisive mandate from the partys internal electorate, Jeremy Corbyn delivered his first annual conference speech as Labour Party leader in Brighton on 29 September 2015. With its slightly tentative delivery and meandering structure, Corbyns speech was met with a lukewarm reaction from the political commentators and journalists who were covering the event for the national media. It was received rather more rapturously by party members within the conference hall. One section of the speech seemed to resonate in particular. Keir Hardie, a former coal miner and one of the founding figures of the Labour Party, died on 26 September 1915. Speaking three days after the centenary anniversary of Hardies death, the new leader of the Labour Party sought to pay homage to this historic figures memory. At the climactic end of his speech, Corbyn proclaimed:

We owe him [Hardie] and so many so much more. And he was asked once, summarise what you are about, summarise what you really mean in your life. And he thought for a moment and he said this: My work has consisted of trying to stir up a divine discontent with wrong. Dont accept injustice, stand up against prejudice.

Writing in The Times , Philip Collins, Tony Blairs former speech writer, noted the effectiveness of this specific passage of Corbyns speech but criticised the speech for being almost all past and party.

When placed in the immediate context of the rise of Corbynism, this speechs historically orientated nature and its emphasis on the partys past were not anomalous. In many ways, Corbyns 2015 leadership campaign had been framed around a perceived need to recapture Labours historic principles and mission. On the campaign trail at the Durham Miners Gala in July, Corbyn recalled the struggles and sacrifices of the Labour Partys

When located in their recent historical context, such public venerations of the partys past were, perhaps, rather surprising. During Labours period in government between 1997 and 2010, it had widely been believed that, under New Labour, the party had been substantially reoriented away from the past and towards the future. Writing in 2002, Peter Mandelson proclaimed that Tony Blair and his supporters had turned Labour into the party of the modern and the future. In September 2015, it appeared that Labours attachment to the past had proven itself to be rather more resilient than the leading figures within the New Labour project had hoped, foreseen and, indeed, later believed.

New Labours critique of Old Labour

Various explanations have been given for New Labours hostility towards the partys past. Academics have tended to stress the strategic nature of the way in which New Labour positioned itself in a temporal sense. James Cronin has argued that members of the New Labour project gained a rhetorical edge over their opponents within the party by portraying themselves as modern, their critics as backward-looking. Yet the distinctions that New Labour made between Old and New Labour were not simply the product of either strategic opportunism or the need to reinvigorate an ailing brand name. They often originated from a genuinely held belief that British society had changed and Labour had not.

More specifically, New Labour argued that Old Labour had been a fundamentally nostalgic party. This idea was often ill-defined, under-developed and lacked any real analytical depth. To a certain extent, it offered a mechanism by which New Labour could signal to the electorate that it had made a distinct break from the partys past.

Tony Blair frequently attacked nostalgia in his speeches, interviews and articles.