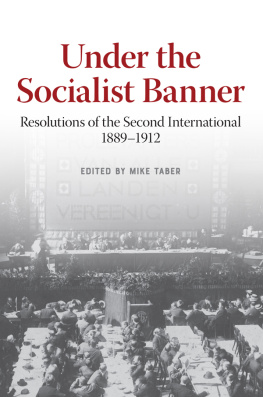

UNDER THE SOCIALIST BANNER

Cover photo and frontispiece: Opening session at 1904 congress of Second International in Amsterdam. Banner in Dutch reads: Proletarians of all lands, unite! Among those at speakers table: Clara Zetkin (second from left, standing and translating), Rosa Luxemburg (fifth from left), Sen Katayama (sixth from left), Hendrick Van Kol (seventh from left), and Georgy Plekhanov (ninth from left). Photographer: Corn. Leenheer. From International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam), call number BG D1/389.

UNDER THE

SOCIALIST

BANNER

RESOLUTIONS OF THE SECOND

INTERNATIONAL, 18891912

Edited by Mike Taber

Introduction

Socialism.

That wordconsidered by some to have been relegated to dusty historical archiveshas once again become a major point of contention in contemporary politics. So much so that US president Donald Trump regularly conjured up the socialist bogeyman as he sought to justify some of the more reactionary policies of his administration. By doing this, however, Trump inadvertently testified to the massive growth of interest in socialism today, especially among young people.

An Axios poll in early 2019 found that 61 percent of US citizens age eighteen to twenty-four viewed socialism in a favorable light. Such sentiment is remarkable given the decades of Cold War antisocialist rhetoric that has inundated US political culture. Another indication of the deepening interest in socialism is the explosive growth of the Democratic Socialists of America, whose membership jumped from six thousand in 2016 to well over ten times that number by early 2020.

Behind this phenomenon of socialisms growing appeal is the dawning recognition by millions of young people and others that capitalism offers them no future. Millions are saddled with student debt, limited job prospects, and knowing they face a standard of living worse than their parents. Young workers face deteriorating wages and working conditions, as well as the ever-present threat of unemployment. Worries about health care, education, and other declining social services confront them at every step. The Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 has laid bare how starkly the profit system stands in contradiction to human needs.

The upsurge around racist police killings that shook the United States and the world in 2020 illustrated how millions are repelled by the horrors they see around them: never-ending imperialist wars; racism and police brutality; escalating attacks on womens rights; anti-immigrant scapegoating and violence; chauvinist hysteria; the growth of ultraright forces; the dehumanization and commodification of social relations. On top of all this, they see a looming catastrophe facing humanity due to the consequences of climate change and environmental destruction. All of these evils appear to them to have a common source: capitalism.

Despite this sentiment, however, relatively few of those now rallying to socialism know much about its history. Nor are most of them fully aware of the revolutionary thrust at the heart of socialisms legacy.

For this reason, an appreciation of the Second Internationaloften referred to as the Socialist Internationalduring the years its resolutions were guided by revolutionary Marxism is particularly relevant.

An International Movement

A central tenet of the socialist movement for over 170 years has been internationalism.

Workers of the world, unite! has been socialisms slogan ever since Karl Marx and Frederick Engels issued this clarion call in the Communist Manifesto, published in 1848. Along these lines, the universal anthem of world socialism has been The Internationale.

Putting that perspective into practice, Marx and Engels in 1864 helped organize and lead the International Workingmens Association, better known as the First International. That association played a vital role in consolidating the emerging working-class movement around the world. It became known in particular for promoting the concept of international working-class solidarity, through the organization of support to strikes and other struggles by working people across borders. As Marx put it in 1872, Let us bear in mind this fundamental principle of the International: solidarity! It is by establishing this life-giving principle on a reliable base among all the workers in all countries that we shall achieve the great aim which we pursue the universal rule of the proletariat.

Due to the primitive conditions of the early working-class movement, the First International had a short life span, declining precipitously after 1872 and formally dissolving in 1876. During the thirteen years that followed, various attempts were made to revive it. All were unsuccessful, however, coming up against the weakness of the organized proletarian movement in most countries. But by 1889, mass working-class parties and a growing trade union movement had begun to emerge. In this context, the world organization that became known as the Second International was founded.

The new movementknown at the time as Social Democracywas formed under the direct guidance of Frederick Engels, who, after Marxs death in 1883, was the recognized leader of world socialism. Among the Second Internationals leading figures over the next twenty-five years were prominent left-wing socialists and Marxists: Eleanor Marx, August Bebel, Wilhelm Liebknecht, Paul Lafargue, Karl Kautsky, Jules Guesde, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, Georgy Plekhanov, Christian Rakovsky, and V. I. Lenin.

The role of Engels in the early years of the Second International is often not fully appreciated. Marxs lifelong collaborator played a central role in the Second Internationals founding in 1889, advising the organizers in detail on virtually all questions related to the political preparation and organization of the founding congress, along with helping to publicize the event. Engels subsequently played an important advisory role in the Second Internationals development up until his death in 1895.

A Heterogeneous Movement

From its beginning, the Second International was a loose association of widely divergent forces, with differing perspectives and expectations.

The movement included in its ranks both political parties and trade unions. A few of the political organizations were mass parties; others were small propaganda groups. Some of these forces had clearly defined Marxist programs; others still bore traits of pre-Marxist brands of socialism, with a multitude of conflicting perspectives, such as anarchism and syndicalism. The three largest contingents of the Second International were those in Germany, with a mass Social Democratic Party and large trade unions that looked to this party; Britain, with a number of relatively apolitical trade unions and a wide assortment of small political organizations; and France, with strong revolutionary traditions, but with the movement divided into opposing political currents.