Dangerous Counsel

Dangerous Counsel

Accountability and Advice in Ancient Greece

MATTHEW LANDAUER

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-65401-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-65379-2 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-65382-2 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226653822.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Landauer, Matthew, author.

Title: Dangerous counsel : accountability and advice in ancient Greece / Matthew Landauer.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009194 | ISBN 9780226654010 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226653792 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226653822 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: GreecePolitics and governmentTo 146 B.C. | Political consultantsGreece. | Government accountabilityGreece. | DemocracyGreece. | DespotismGreece. | Comparative government.

Classification: LCC JC73 .L25 2019 | DDC 320.938dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009194

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

This project has benefited from the advice of many over the yearsalthough, of course, responsibility for the finished product is mine alone. For conversations and comments, I wish to thank in particular Danielle Allen, Ryan Balot, Shadi Bartsch, Eric Beerbohm, Susan Bickford, Jonathan Bruno, Agnes Callard, Daniela Cammack, Federica Carugati, Josh Cherniss, Chiara Cordelli, Prithvi Datta, Mark Fisher, Jill Frank, Adom Getachew, Sean Gray, Kinch Hoekstra, Sean Ingham, Seth Jaffe, Demetra Kasimis, Tae-Yeoun Keum, John Lombardini, Melissa Lane, Harvey Mansfield, Patchen Markell, Liz Markovits, John McCormick, Christopher Meckstroth, Yascha Mounk, Joe Muller, Sankar Muthu, Eric Nelson, Michael Nitsch, Josh Ober, Jennifer Pitts, Sabeel Rahman, Nancy Rosenblum, Arlene Saxonhouse, Melissa Schwartzberg, Joel Schlosser, Matthew Simonton, Lucas Stanczyk, Christina Tarnopolsky, Andrea Tivig, Don Tontiplaphol, Richard Tuck, Lisa Wedeen, James Wilson, Carla Yumatle, Bernardo Zacka, Linda Zerilli, and John Zumbrunnen. In addition, audiences at Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, the University of Chicago, and conferences around the country have listened to various iterations of the arguments in the book, providing sharp questions, helpful feedback, and encouragement.

My fellow political theorists and political scientists at the University of Chicagostudents and professors alikeas well as those studying ancient ethics and politics in other departments, have provided an ideal intellectual community to finish writing the book. Final edits to the manuscript were completed while I was a Laurance S. Rockefeller Visiting Faculty Fellow at the Princeton University Center for Human Values. I thank Katie Dennis for her invaluable editorial assistance and comments at this stage.

Two anonymous reviewers from the University of Chicago Press provided in-depth comments on the entire manuscript, spurring me to make a number of additions to the argument. Chuck Myers, Jenni Fry, Holly Smith, and Alicia Sparrow expertly shepherded me through the editorial process. I thank Pam Scholefield for creating the index.

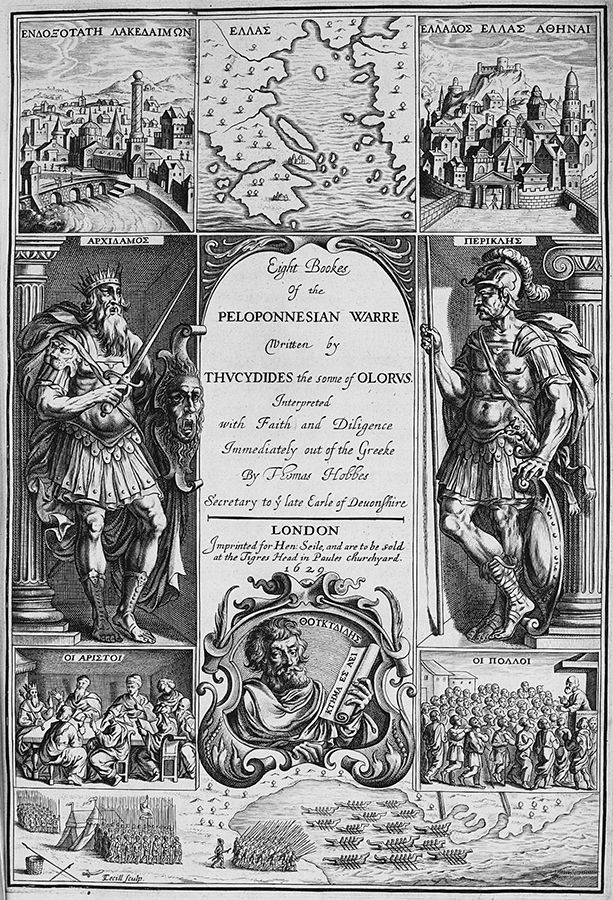

Sections of chapters appeared as Parrhesia and the Demos Tyrannos: Frank Speech, Flattery and Accountability in Democratic Athens in History of Political Thought 33, no. 2 (2012): 185208. Figure 1, Frontispiece to Hobbes translation of Thucydides Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre (1629), is printed with permission of the Princeton University Library. Figure 2, Demos personified and crowned by the goddess Dmokratia, is printed with permission of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

My mother, Hollis Landauer, and my sisters, Melissa and Rachel, have provided encouragement and support. I have told them to stop asking me when the book is coming outI am glad to be able to say to them, Now. Emma Saunders-Hastings is my closest adviser and partner in all things, and this book would not exist without her help. It is my father Michael Landauers fault that I am a political scientist (he gave me his copy of Laswells Politics: Who Gets What, When, How when I was in high school), and I dedicate this book to his memory.

I. Picturing Political Debate

In the frontispiece to Hobbes translation of Thucydides Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre (1629), one can find, underneath towering portraits of Pericles of Athens and Archidamus of Sparta, two comparatively tiny depictions of political decision-making in action (see The scene is meant to illustrate the workings of a democratic assembly. On the left, we have hoi aristoi, the (self-styled) best men, conversing around a table. If hoi polloi represent Athens, then this council of hoi aristoi must take place in Sparta.

FIGURE 1. Frontispiece to Hobbes translation of Thucydides Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre (1629)

The images are political caricatures, meant to provoke judgments about the relative quality of political discourse depicted in each scene. We can imagine the orator haranguing the crowd below, whipping them into a frenzy with the force of his words, manipulating and deceiving them. In contrast, we see the men at the table debating calmly and rationally: witness the two in the corner, consulting a book and each other, preparing to share their findings with the rest of the group. We are meant to see the superiority of decision-making and political discourse among the few best over decision-making and discourse among the many.

Yet setting aside their ideological slant, we can also see that the images depict a basic structural difference. The image of hoi polloi depicts a single speaker set off from a crowd. In one sense, his singularity is purely incidental; if we were to let the scene run its course, we could readily imagine other speakers eagerly taking their turn to persuade the audience. However, it is also an essential part of the structure of this kind of decision-making that Nonetheless, the audience is not passive, for they ultimately have the power to decide on the issues put before them. At the end of the speeches, it is they who vote on what is to be done. The orator can only attempt to persuade and advise them.

In contrast, no single figure among hoi aristoi occupies the position of the orator. If we were to unpause the action depicted in this image, we would find ourselves in the midst of a lively debate. Decision-making in Athens relied on a division of labor between speaker and audience, but the roles at this table are much more fluid. The picture of hoi polloi has two nodes, speaker and audience; by contrast, the lines of communication at the table flow freely and in multiple directions. Each man, we are meant to see, is participating in the discussion, speaking and listening in turn.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).