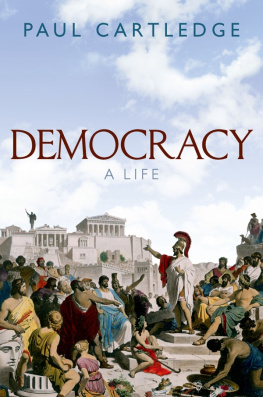

DEMOCRACY

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Paul Cartledge 2016

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2016

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015034058

ISBN 9780199697670

ebook ISBN 9780191079184

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

To Josh Ober in friendship and with admiration

And to the memory of Freeborn John Lilburne (b. c. 1615, d. 1657)

CONTENTS

This is not my first crack at democracy, mainly ancient Greek. In 2008 I published, in German translation, the book of a series of lectures I was invited to deliver at the University of Heidelberg (Cartledge 2008). This came about through the good offices chiefly of Professor Joseph Maran, aided and abetted by Professor Tonio Hlscher, to both of whom I owe a great deal, and not only for their immensely friendly hospitality. In 2009 I published a book on ancient Greek political thought (as opposed to theory) from Homer to Plutarch (roughly c. 700 BCE to CE 100), in which democracy served as the guiding red thread (Cartledge 2009b). And I have published a number of articles on aspects of democracy ancient and modern (e.g., Cartledge 1996a, 2000). But these were all early runs at the subject. The real work begins here.

The present book has been several years in the making. Most immediately, it is based squarely upon a set of advanced, final-year undergraduate lectures that I delivered in Cambridge over four successive academic years (from 2009 to 2013), both to undergraduate students taking the Classical Tripos and to those studying for the Historical Tripos. The lecture course was titled Ancient Greek Democracyand its Legacies, although for reasons that will become apparent I would have preferred Ancient Greek Democracies. Since all or most of the Historians who opted to take the course and the attached examination paper (about ten in each of the four years) knew little or no ancient Greek, the programme was firmly billed as a course in translation, a fact of which I tried to make a virtue. In this, as in many other respects, I had the shining example of the late Sir Moses Finley (Professor of Ancient History at Cambridge from 1970 to 1979) to guide me. It was to him (and also to the late Professor Pierre Vidal-Naquet) that in profound homage I dedicated my Ancient Greek Political Thought in Practice (Cartledge 2009).

In advertising and executing the course of lectures I announced six principal aims:

1. To explore the meanings of democracy both ancient (in Greek: demokratia) and modern (including current);

2. To enhance understanding of the special circumstances required to make possible both the emergence and the continuation of People Power (demokratia) at Athens;

3. To compare and contrast the democracy (democracies) that were created in Athens with those to be found elsewhere in the Greek world, a world ofat most periods from about 600 BCE on1,000 or so citizen-states (poleis);

4. To appreciate the development of ancient political thinking and theory about democracy, and not least comprehend their typically anti-democratic bent;

5. To track the devolution or degradation of the original Greek conceptions and practices of democracy through the Hellenistic Greek world, late Republican and early Imperial Rome, and down as far as early Byzantium (6th c. CE); and

6. To follow some of the trajectory of post-Ancient democracy, in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance, in Revolutionary England, America and France, and in its reconstituted or reinvented forms of the nineteenth century and beyond.

I further issued a prospectus, to the following effect:

All historiography may be contemporary history, but the historiography of democracy could hardly be more so. The current global preoccupation with democracy and (for some) its global extension makes constant re-examination of the original ancient Greek versions imperative. This course will thus be explicitly and determinedly comparativist from the outset, and one early pedagogical aim will be to problematize and defamiliarize Modern democracy and thus to sever any easy assimilation of it to (any) Ancient (prologue).

).

Ancient Greek, especially ancient Athenian, democracy (to 322/1 BCE) was to be the main topic of the course ().

More briefly, I concluded, we would look finally at some foreshadowings or inklings of modern democracy as vaguely sketched in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance ().

), certainly would be; so that we would end on a paradox, one that I still find quite baffling, actually. Until the first half of the nineteenth century the dominant tradition of Western political thought both in and since Antiquity had been anti-democratic, opposed, specifically, to the more radical species of democracy theorized by Aristotle in the Politics. That long tradition has been and is still today being actively undermined, although it is as yet far from being overthrown, by various shapes and forms of direct democracy advocates, including those who point to thetechnicalcapacity of new information technology to realise the global democratic village. Against them, however, looms the spectre of a globalized political world order dominated by a country and state-form, the Peoples Republic of China, entirely lacking in any sort of Western-style democratic tradition whatsoever. Back to the future? It might well turn out to be just a pious wish (epilogue).

That prospectus was quite closely adhered to in the lectures, although they differed in detail and sometimes more than just in detail year on year, as they were always given ex tempore