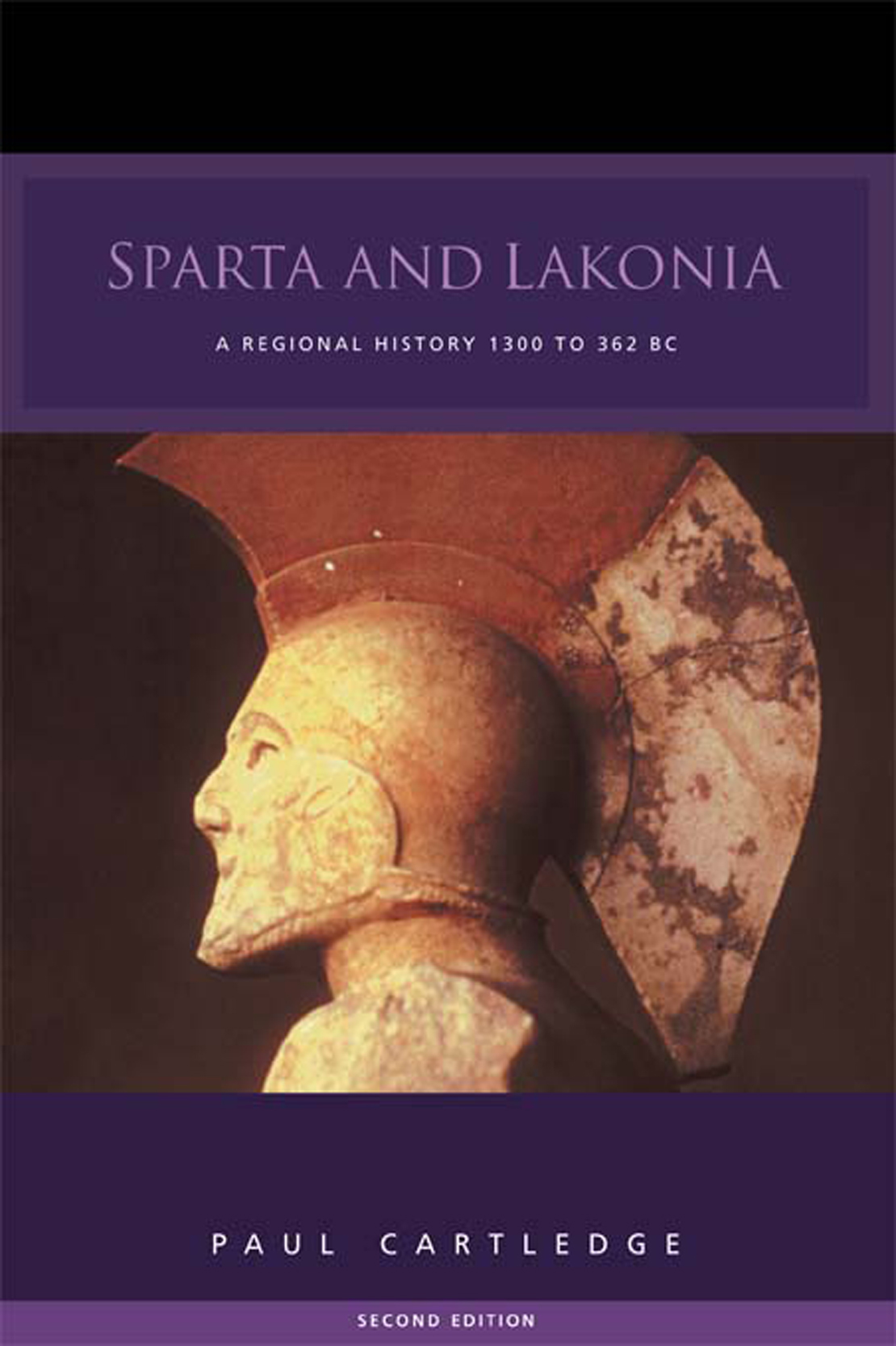

Sparta and Lakonia

Sparta and Lakonia

A regional history 1300362 BC

Paul Cartledge

First published 1979

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Second edition first published 2002

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

1979, 2002 Paul Cartledge

Typeset in Times Ten by Keystroke, Jacaranda Lodge, Wolverhampton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN 0415263565 (Hbk)

ISBN 0415262763 (Pbk)

To Judith Portrait (again)

Contents

Figures

Preface

The basis of this book was laid in an unpublished doctoral thesis Early Sparta c. 950650 BC: an Archaeological and Historical Study (Oxford 1975). To my former supervisor, Professor J. Boardman, and my examiners, Professors C.M. Robertson and W.G. Forrest, I am principally indebted for its conception and fruition. It could not, however, have been completed without the unstinting assistance of many archaeologists, historians and geographers, the staffs of museums and libraries in Greece, Ireland and England, and grants from research funds in the Universities of Dublin and Oxford. The following scholars and friends are owed especial thanks: R. Beckinsale, D. Bell, J.N. Coldstream, K. Demakopoulou-Papantoniou, the late V. Desborough, L. Marangou, G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, G. Steinhauer (Acting Ephor of Lakonia), E. Touloupa, P.M. Warren, J.G. Younger.

The present book represents a considerable expansion, conceptual as well as geographical and chronological, of the thesis. It is not primarily a political history, but an attempt, inevitably provisional, to map out a new kind of history of ancient Sparta one which does justice as well to the area unified and exploited by the Spartans as to the inhabitants of the central place. The inspiration to write it was provided by the invitation of Professor R.F. Willetts to contribute to the series of which he is general editor. I wish to thank him and Mr N. Franklin for their constant encouragement and helpful criticism. Drafts of various chapters have also been read and greatly improved by O.T.P.K. Dickinson, W.W. Phelps, J.B. Salmon and G.E.M. de Ste. Croix. None of these of course should be regarded as incriminated by the results, for which I alone bear full responsibility.

I am also most grateful to the following for permission to reproduce, sometimes in modified form, published maps and illustrations: the Managing Committee of the British School at Athens; the Swedish Institute in Athens; J. Bintliff, J.N. Coldstream, R. Hope Simpson and W.A. McDonald (Director of the Minnesota Messenia Expedition).

Trinity College, Dublin

June 1978, P.A.C.

Preface to the second edition

The original edition of this book was commissioned by Norman Franklin, when Routledge was Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd and operated out of London, Henley, and Boston. This new edition was commissioned by Dr Richard Stoneman, by which time Routledge had become part of Taylor & Francis and was based in London and New York. I am most grateful to Richard for suggesting this republication and for his patience in awaiting what I hope are the improvements I have been able to effect. Errors of one sort and another in the original edition have been silently corrected. An appendix (below, pp. 31522) deals briefly with the books reception and lists certain bibliographical addenda covering the period 19792000, paying special regard to the books particular conception as a regional history. I am most grateful to all those colleagues, scholars and friends who have written to me pointing out errors or other deficiencies; they include: Michel Austin, Ephraim David, David Harvey, Stephen Hodkinson, Pavel Oliva, Richard Talbert, and Helen Waterhouse.

February 2001, P.A.C.

Notes on the spelling of Greek words and on dates

Consistency in the transliteration of Greek words is impossible of attainment. In general I have preferred to reproduce Greek letters by their nearest English equivalents rather than Latinize them: thus Krokeai not Croceae, Lykourgos not Lycurgus. On the other hand, Lysandros for Lysander, and similarly for other household names, must have seemed merely pedantic.

Unless otherwise specified, all dates are BC.

Introduction

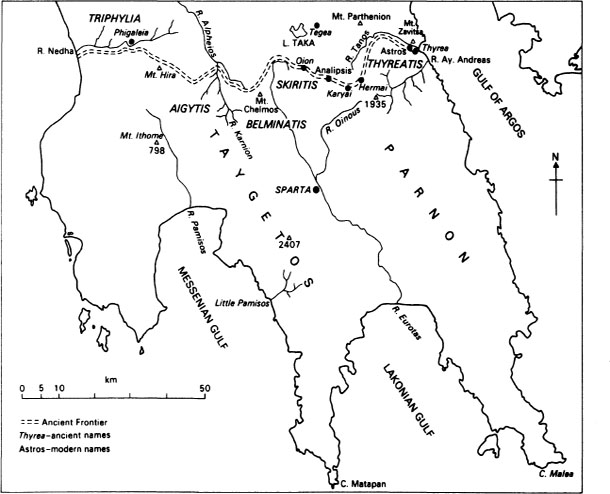

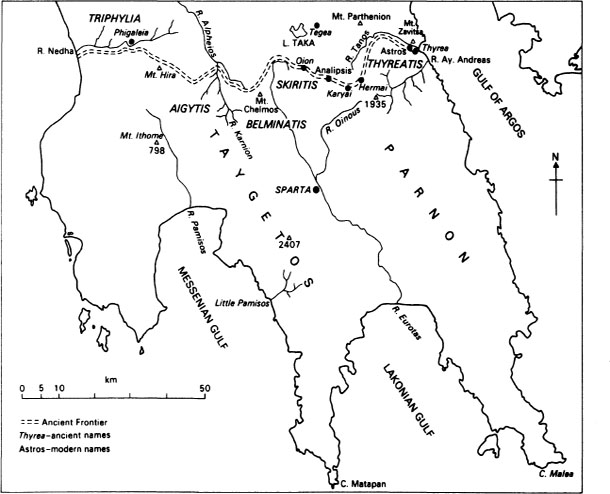

Figure 1 The frontiers of Sparta c. 545

Chapter one

Boundaries

Without a geographical basis the people, the makers of history, seem to be walking on air. So wrote Jules Michelet in the 1869 Preface to his celebrated Histoire de France but in vain, it seems, so far as most historians of Sparta have been concerned. For it remains as true of them today as it was of historians in general in the nineteenth century that, once the de rigueur introductory sketch of geographical conditions is out of the way, the substantive analysis or narrative proceeds as if these complex influences ... had never varied in power or method during the course of a peoples history (Febvre 1925, 12).

There is, however, perhaps even less excuse for this outmoded and harmful attitude in studying classical Sparta than in studying some other ancient Greek states. For, as is well known, the Spartans throughout the period of their greatest territorial expansion and political supremacy (c. 550370) rested their power and prosperity on the necessarily broad backs of the Helots, the unfree agricultural labourers who lived concentrated in the relatively fertile riverine valleys of the Eurotas in Lakonia and the Pamisos in Messenia. And besides the Helots there literally dwelt round about the Perioikoi, who were free men living in partially autonomous communities and providing certain essential services for the Spartans but farming more marginal land. Any serious account of Spartan history therefore is obliged to make more than a token gesture at understanding the mutual relationships of these three groups of population. Thus it is with the infrastructure of land allotments, helots and perioeci, with everything that includes with respect to labour, production and circulation (Finley 1975, 162) that this study will be primarily concerned, in a determined effort to bring the Spartans firmly down to earth.

In this connection it is encouraging to note the recent upturn of interest in a more broadly geographical and materialist approach to Graeco-Roman antiquity not to mention prehistoric Mediterranean studies, where, as we shall see in more detail in recently defined a major desideratum as close study, region by region, of the changing patterns of land use and agricultural production, supported by analysis of demographic and other socio-economic data provided by our sources (White 1967, 78). This applies equally to Greece. Moreover, not only does he state the objective clearly, but he conveys too the limitation imposed by the available evidence.