Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy

Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy

THE POLITICS OF EXPULSION

IN ANCIENT GREECE

Sara Forsdyke

PRINCETION UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETION AND OXFORD

Copyright 2005 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

ISBN: 0-691-11975-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Forsdyke, Sara, 1967

Exile, ostracism, and democracy : the politics of expulsion in ancient Greece / Sara Forsdyke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-1-40082-686-5

1.Exile (Punishment)GreeceAthensHistory.2.Power (Social sciences)GreeceAthensHistory.3.Political crimes and offensesGreeceAthensHistory.4.DemocracyGreeceAthensHistory.5.Athens (Greece)Politics and government. I. Title.

JC75.E9F67 2005

364.6'8dc222004065773

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Electra

Printed on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Finn, Thomas, and Sophie

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS study originates in Princeton PhD dissertation, but has been completely rewritten and expanded. I would like to acknowledge, however, the support and guidance I received from the members of the Classics Department during my years at Princeton. In particular, Josh Ober not only provided a brilliant example of intellectual energy and insight, but was a model of conscientious and empathetic mentorship.

I owe a great deal to my colleagues in the Department of Classical Studies and the Department of History at the University of Michigan. It is a great privilege to be surrounded by such a group of diverse, talented, and energetic scholars. I have frequently availed myself of their knowledge and advice, and they have always responded with great generosity. In particular, I would like to thank Benjamin Acosta-Hughes, Sue Alcock, Don Cameron, John Cherry, Derek Collins, Beate Dignas, Bruce Frier, Sally Humphreys, Sabine MacCormack, David Potter, Ruth Scodel, and Ray Van Dam. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Sharon Herbert, who as chair provided support in important ways. I would also like a acknowledge the departments talented graduate students. Their inquisitiveness and critical thinking have provided further stimulus to broaden and deepen my thoughts.

I would like to thank the members of the Classics Department at the University of Chicago for their hospitality during a year of leave (2000 2001). In particular, I benefited from the kindness and learning of Danielle Allen, Shadi Bartsch, Chris Faraone, Jonathan Hall, and James Redfield. A symposium on the ritual aspects of ostracism held in Chicago in May 2001 was particularly helpful for clarifying my thoughts on the relation between ostracism, religion, and magical practices.

I am grateful to the following scholars who have read chapters in advance or answered my inquiries: Susan Alcock, Ryan Balot, Stefan Brenne, Paul Cartledge, Walter Donlan, Antony Edwards, Lisa Nevett, Robin Osborne, Walter Scheidel, Ruth Scodel, James Sickinger, and Peter Siewert. Robert Chenault read through the entire manuscript with an eagle eye, and saved me from many errors and inconsistencies. I thank Charles Myers and Jennifer Nippins of Princeton University Press for their expert and friendly editorial assistance.

An earlier version of parts of chapters 2, 3, and 4 appeared in article form as "Exile, Ostracism, and the Athenian Democracy" in Classical Antiquity 19 (2000): 23263. For permission to reprint this material, I thank the University of California Press.

Finally, friends and family. Among the many good friends that I have made in my academic career, the opportunity to discuss work and life with Ryan Balot and Sarah Harrell has been invaluable to me. Einer, Oddbjorg, Helena, and Per Larsen have followed the progress of my work from afar, and I thank them for their kind support. My parents, Pat and Don Forsdyke, always encouraged me to follow my interests, even when these took me in unexpected directions. I am grateful to them, and to my three sisters, Ruth Polly, and Charlotte, for their love and support, particularly in difficult times.

My deepest gratitude goes to my husband, Finn Larsen. Although he has not read a word of this book, his love, companionship, and many sacrifices have made its writing much easier. I dedicate the book to him, and to our two children, Thomas and Sophie, for all they have given me.

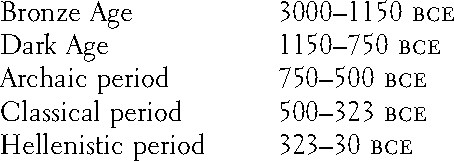

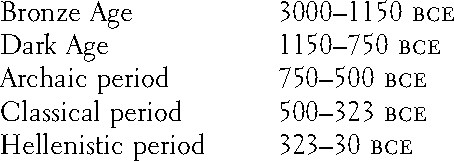

CHRONOLOGY

Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy

Introduction

PROBLEMS, METHODS, CONCEPTS

When we cannot get a proverb, or a joke, or a ritual, or a poem, we know we are on to something. By picking at the document where it is most opaque, we may be able to unravel an alien system of meaning. The thread might even lead into a strange and wonderful world view.

Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre

PERHAPS no ancient Greek practice is more opaque to us than the Athenian institution of ostracism. Scholars have repeatedly labeled it bizarre, intrinsically paradoxical, and exotic. If we follow Darntons exhortation (1984: 5), however, our puzzlement is not a cause for dismay, but a signal of fertile territory for the acquisition of a new perspective on the ancient Greek past. In many ways, I hope that the study that follows validates Darntons claim. By investigating ostracism, I have sought to open new perspectives not simply on one particular practice, but on broader attitudes and developments in Greek culture and society. In particular, I hope that by exploring the historical origins and cultural and ideological meanings of ostracism, I shed new light on such central topics as the rise of the polis, the origins of democracy, and the relation between historical events, cultural practices, and the ways that society represents itself to itself.

THE ARGUMENT

The main argument of this book is that there was a strong connection between exile and political power in archaic and classical Greece, and that this relation had a formative effect on the institutional and ideological development of the Greek city-states  , poleis). Specifically, I argue that in the archaic period (c. 750500), elites engaged in violent competition for power and frequently expelled one another from their poleis. I label this form of political conflict the "politics of exile," and I suggest that it was particularly unstable, since exiled elites often called on foreign allies to help them return to their poleis and expel their opponents in turn. Many of the institutional developments of the archaic poleis can be viewed as attempts by elites to prevent violent conflict over power and the political instability that it caused. By instituting formal public offices and establishing laws, for example, elites attempted to enforce the orderly rotation of political authority among themselves. These attempts at elite self-regulation, however, were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing violent intra-elite conflict, although they played an important role in strengthening the civic structures of the early Greek poleis (chapters 1 and 2).

, poleis). Specifically, I argue that in the archaic period (c. 750500), elites engaged in violent competition for power and frequently expelled one another from their poleis. I label this form of political conflict the "politics of exile," and I suggest that it was particularly unstable, since exiled elites often called on foreign allies to help them return to their poleis and expel their opponents in turn. Many of the institutional developments of the archaic poleis can be viewed as attempts by elites to prevent violent conflict over power and the political instability that it caused. By instituting formal public offices and establishing laws, for example, elites attempted to enforce the orderly rotation of political authority among themselves. These attempts at elite self-regulation, however, were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing violent intra-elite conflict, although they played an important role in strengthening the civic structures of the early Greek poleis (chapters 1 and 2).

Next page

, poleis). Specifically, I argue that in the archaic period (c. 750500), elites engaged in violent competition for power and frequently expelled one another from their poleis. I label this form of political conflict the "politics of exile," and I suggest that it was particularly unstable, since exiled elites often called on foreign allies to help them return to their poleis and expel their opponents in turn. Many of the institutional developments of the archaic poleis can be viewed as attempts by elites to prevent violent conflict over power and the political instability that it caused. By instituting formal public offices and establishing laws, for example, elites attempted to enforce the orderly rotation of political authority among themselves. These attempts at elite self-regulation, however, were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing violent intra-elite conflict, although they played an important role in strengthening the civic structures of the early Greek poleis (chapters 1 and 2).

, poleis). Specifically, I argue that in the archaic period (c. 750500), elites engaged in violent competition for power and frequently expelled one another from their poleis. I label this form of political conflict the "politics of exile," and I suggest that it was particularly unstable, since exiled elites often called on foreign allies to help them return to their poleis and expel their opponents in turn. Many of the institutional developments of the archaic poleis can be viewed as attempts by elites to prevent violent conflict over power and the political instability that it caused. By instituting formal public offices and establishing laws, for example, elites attempted to enforce the orderly rotation of political authority among themselves. These attempts at elite self-regulation, however, were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing violent intra-elite conflict, although they played an important role in strengthening the civic structures of the early Greek poleis (chapters 1 and 2).