2015 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weiner, Greg.

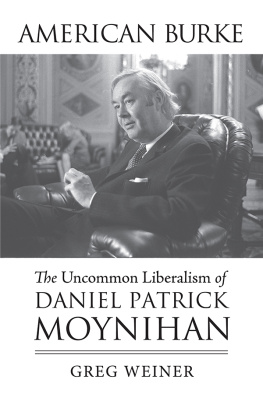

American Burke : the uncommon liberalism of Daniel Patrick Moynihan / Greg Weiner.

pages cm (American political thought)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-2096-8 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2097-5 (ebook)

1. Moynihan, Daniel P. (Daniel Patrick), 19272003Political and social views. 2. LiberalismUnited States. 3. United StatesPolitics and governmentPhilosophy. 4. United StatesSocial policyPhilosophy. 5. Burke, Edmund, 17291797Political and social views. 6. LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. 7. StatesmenUnited StatesBiography. 8. ScholarsUnited States--Biography. 9. United States. Congress. SenateBiography. I. Title.

E 840.8. M 68 W 34 2015

973.92092dc23

2014040566

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials z39.481992.

For George W. Carey

Requiescat in pace

There is only one political poem of the twentieth century I

consider worth remembering, and that is Yeatss Parnell.

Parnell came down the road, he said to a cheering man:

Ireland shall get her freedom and you still break stone.

This is the knowledge life gives us, and it is indispensable to

politics. And yet how alien to it.

D ANIEL P ATRICK M OYNIHAN , C OPING , 1973

The lively sense that liberals have of the possibility of progress

is matched by a conservative sense of the possibility of decline.

Both concerns need attending.

M OYNIHAN , C OUNTING O UR B LESSINGS , 1980

Democrats... have known good times and bad. Sometimes we

have merely endured. But more often, we have embodied a

great idea, which is that an elected government can be the

instrument of the common purpose of a free people; that

government can embrace great causes; and do great things.

M OYNIHAN , G RIDIRON C LUB , 1981

Preface and Acknowledgments

I cannot say I knew Pat Moynihan. I met him; as an aide for several years to one of his closest friends in the US Senate, Bob Kerrey of Nebraska, I was around him occasionally, but only that. My most vivid memory is watching him walk away one night from an anteroom off the minority leaders office on the Senate side of the Capitol. Kerrey had commandeered it to rehearse a presentation his staff had put together on his Social Security reform proposal, a combination of individual accounts and benefit adjustments, a cause in which Moynihan would soon join him. This was before PowerPoint became such a craze, or crutch, that speakers grew incapable of public utterances without it, and it seemed innovative that we were using some form of technologyprecisely what that was escapes me nowto present the plan visually. What I do recall is that, for some reason, it included the dancing baby that was the early Internet rage of the mid-1990s, I think to illustrate Kerreys proposal for endowing every child with a retirement account at birth. Moynihan happened to walk by; Kerrey nabbed him and showed the presentation. Afterward, there was Moynihan, his six-foot-five frame jaunting away, remarking amiably in something just above a mutter, Ill be goddamned!

So I did not know him. But I admired him, and it is best to put forth at the outset that this is an admiring book. I hope it is not a fawning one, and the intent is for it to be as objectively exegetical as possible. I have endeavored for the most part neither to object nor to endorse but rather to explain. I trust the reader has picked up this book out of interest in Moynihans views, not mine, and though I have assumed a perspective on the import and orientation of his thoughtand that I do present herethe objective is to allow Moynihan to speak for himself.

The perspective is twofold. First, I will argue that Moynihan was a liberalI use the term here and throughout in its conversational reference to a politics that believes in a robust ameliorative role for governmentof a type no longer present in American political conversation, what I have chosen to call a Burkean liberal. It bears emphasizing now, though I repeat the qualification several times in the main body of the text as well, that my claim is not that Burke influenced Moynihan, although there are indications that, at least around the margins, he did; explicit references to Burke appear at least two dozen times in Moynihans hand in my several hundred pages of notes on his writings, which surely are not comprehensive.

Second, I will contend that American politics is impoverished for the loss of Burkean liberalism and would be enriched by its reclamation, regardless of whether one agrees with its tenets. Consequently, in the concluding chapterwhich, it is vital to emphasize, consists largely of my own ideas, inflected by Moynihan but not attributable to himI will look beyond Moynihan, drawing on his thought to explore what the elements of a contemporary Burkean liberalism might be. The idea is not that Moynihans thought contains the elements of a consistent Burkean liberalism free of nuance but rather that it can inspire them. Therefore, I have stated as strong and clear a case for that concept as I can in the closing chapter.

The idea of Burkean liberalism uniting the poles of promise (aspirations for government) and prudence (awareness of its limits) may seem contradictory. I contend it is not. Burke is available to liberals of a certain cast, although I shall also argue that Burkean liberals and Burkean conservativeswhich is to say Burkeans simplyhave more in common with each other than with other partisans who travel under the same labels they do. I contrast Burkean liberals, in the conclusion, with Progressives and Burkean conservatives with Tea Party populists. In any case, the noun seems less important than the modifier; put otherwise, the argument favors neither liberalism nor conservatism as those terms are contemporarily used. Instead, the assertion is that Burkeanism can accommodate a wider range of views than is commonly supposed. My teacher George W. Carey was once asked whether he considered himself a conservative. Remarking that the word had been drained of meaning in contemporary discourse, he thought for a moment and replied that he considered himself a Burkean. One could be called worse.

Titles naturally simplify. To call Moynihan an American Burke is to make a simple claim about two immensely complex figures whose most common trait is their defiance of easy labels. The claim is neither that Moynihan was a conservative nor that Burke was a liberal. Neither is true; as the subtitle indicates, Moynihans liberalism was his own, but he was a liberal through and through. Still, the compatibilities between Burke and Moynihan are striking. There is, of course, the bare biographical fact that both grew from commonplace Irish roots to the heights of statesmanship. But the commonalities run far deeper. Both stood at the intersection of thought and action, scholarship and statesmanship. Each made his name as an advocate for the disadvantaged and oppressed of his day: Burke for the Catholics of Ireland, the colonists of America, the oppressed of India; Moynihan for the dependent poor in America and the imprisoned millions of the Soviet empire. Both made lonely but stirring rhetorical stands against the totalitarianism of their times: Burke against the French Revolution, Moynihan against Leninist tyranny. Both were conserving reformers who valued traditional systems of authority, most primarily the family and, in the phrase of Burkes to which Moynihan most often recurred, the little platoons of societywhat for Burke were social classes and for Moynihan were ethnic groupings. Each interpreted politics in terms of the observable and concrete rather than the metaphysical and abstract, defended legislative government against executive encroachment, devoted himself to political partyand more.