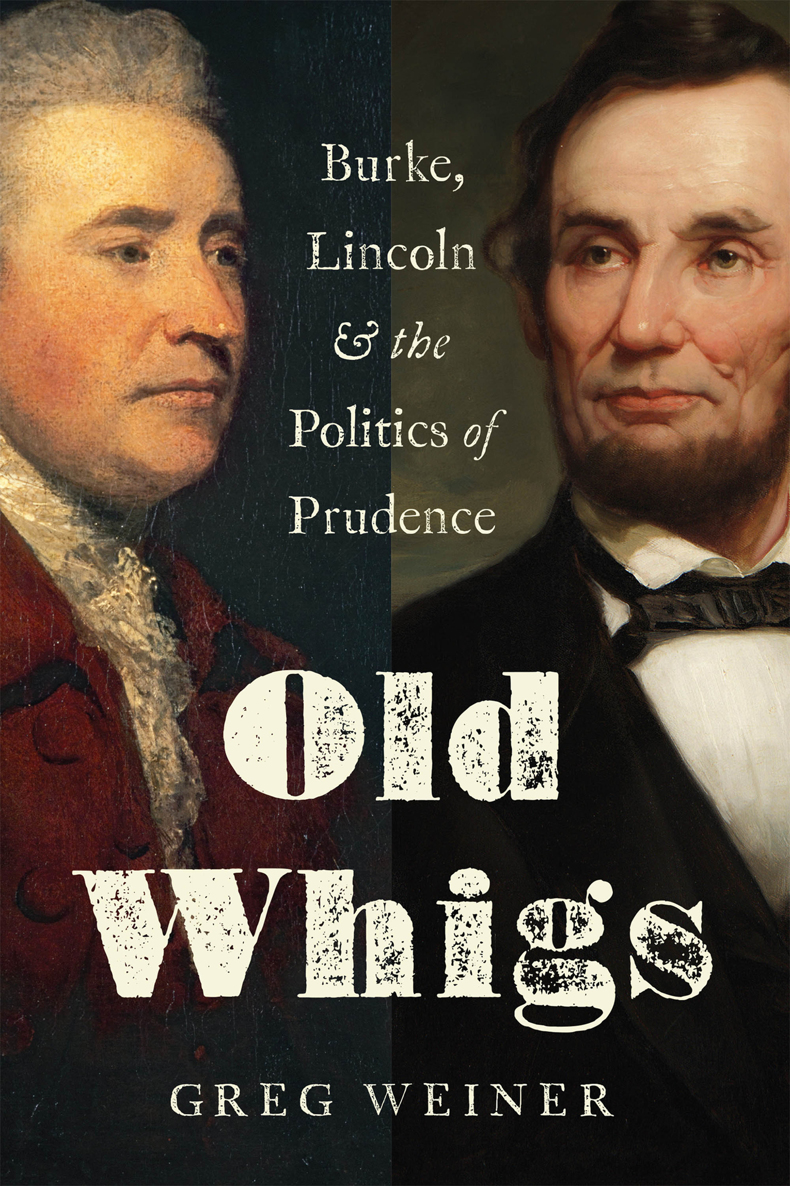

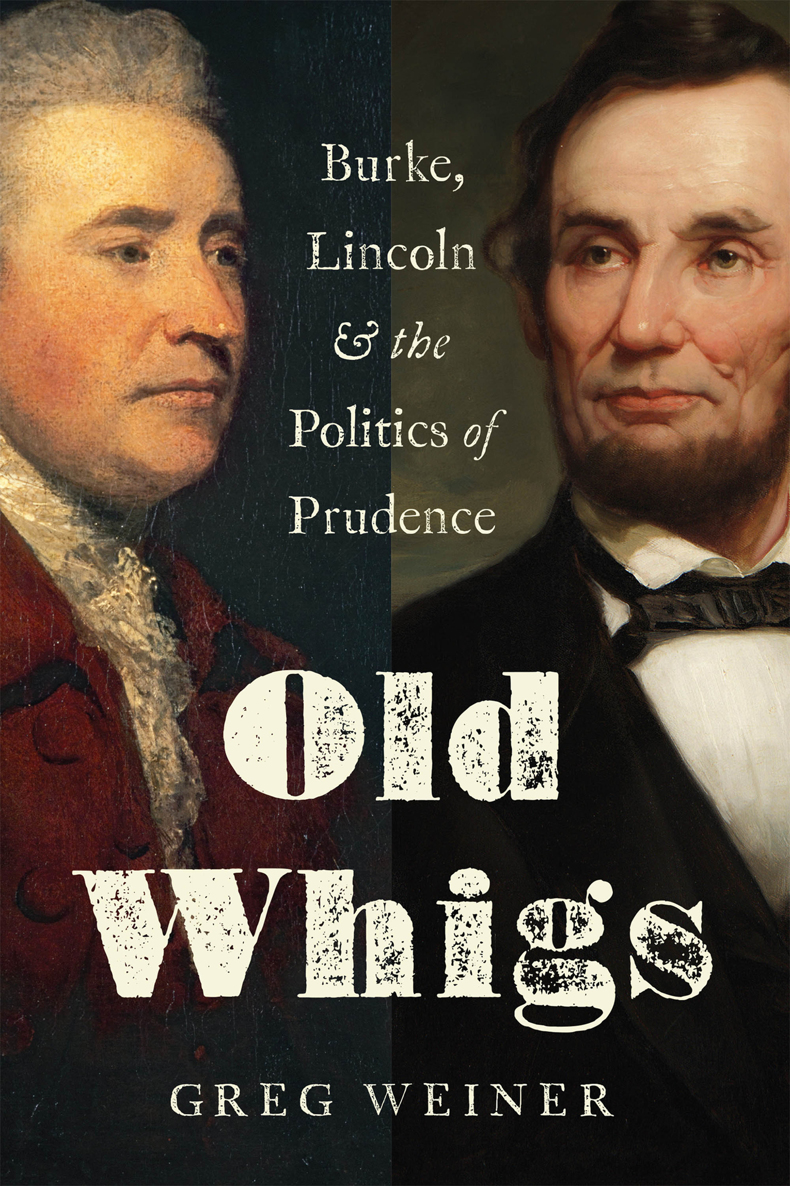

Old Whigs

Old Whigs

Burke, Lincoln, and the Politics of Prudence

Greg Weiner

2019 by Greg Weiner

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2019 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States and printed on acid-free paper. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Weiner, Greg, author.

Title: Old Whigs : Burke, Lincoln, and the politics of prudence / by Greg Weiner.

Description: New York : Encounter Books, [2019] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018053320 (print) | LCCN 2019010769 (ebook) | ISBN 9781641770514 (ebook) | ISBN 9781641770507 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Political leadershipMoral and ethical aspects. | PrudencePolitical aspects. | Burke, Edmund, 17291797Political and social views. | Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Political and social views. | Whig Party (Great Britain)History. | Whig Party (U.S.)History. | Political scienceGreat BritainHistory18th century. | United StatesPolitics and government19th century.

Classification: LCC JC330.3 (ebook) | LCC JC330.3 .W45 2019 (print) | DDC 172dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053320

But the reason why things are ordained to their end is, properly speaking, providence, because it is the principal part of prudence. The other two parts of prudence, memory of the past and understanding of the present, are subordinate to it, helping us to decide how to provide for the future.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica

A disposition to preserve, and an ability to improve, taken together, would be my standard of a statesman.

Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France

And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

Lincoln to General Joseph Hooker, January 26, 1863

Dedication

For my parents

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

In this as in all such undertakings, I have incurred substantial debts, intellectual and personal alike. At some point I will make an honest writer of myself and give my Assumption College colleague Daniel J. Mahoney a co-author credit on everything I write. His intellectual partnership is that integral; my only hesitation is imputing responsibility to him for my errors. Daniel P. Maher of Assumptions Department of Philosophy has also been generous with his time and insight as a guide to Aristotle and far more. Marc Guerra of the Colleges Department of Theology has tutored me in Aquinas and classical prudence, among other topics. The College also provided me with a sabbatical during which I undertook research for this project, for which I am indebted to its president, Francesco Cesareo, and its provost, Louise Carroll Keeley. To my other colleagues in political science, Bernard J. Dobski, Jeremy Geddert, Deborah OMalley, and Geoffrey Vaughan, I am grateful for conversation and collegiality that far exceed what friends at other institutions report is available to them. I am also grateful to Yuval Levin for conversation and counsel on Burke. Errors are, of course, my own.

Roger Kimball of Encounter Books saw promise in this project. I am deeply thankful to him and to his editorial team for that and for their consummate skill in bringing it to fruition.

As I write these words on a Sunday afternoon, my familymy wife, Rebecca, and my children, Hannah, Jacob, and Theodoreare once more tolerating my absence, absent-mindedness, or both. More than that patience, I am grateful for their examples of relentless inquiry, prudence, and moral imagination.

Introduction

Edmund Burke was convinced the Jacobins were coming for his bones.

He had been unrelenting in his opposition to the French Revolution, resisting peace talks with the Directory even when its march across Europe and, perhaps, the sceptered isle itself seemed inexorable. By the time of his death, Burke, seeing Jacobinism victorious abroad and teeming at home, had asked to be buried in an unmarked grave lest the revolutionaries desecrate his remains. His resting place is unknown to this day. The great modern theorist of prudence had, if we interpret the term simplistically, been singularly imprudentwhich is to say incautiousin this as in other projects: defending the rights of the American colonists; his similarly controversial advocacy on behalf of Irish Catholics; his years-long and doomed prosecution of Warren Hastings, the brutal and corrupt governor-general of India.

Abraham Lincoln, too, spurned caution insofar as we understand that term to mean a disposition to surrender to long odds. He insisted on union, believing in victory even after calamities early in the Civil War made it seem untenable. He refused to suspend the 1864 presidential election even when, as late as August of that year, it appeared he would lose and the White House would fall to the accommodationist Democrat and spurned general George B. McClellan. Even in the moment of triumph, Lincolns Second Inaugural declared that North and South shared blame for the torrents of blood.

Yet both Burke and Lincoln, this study argues, are best understood as prudent statesmen. In the entire political lexicon, perhaps no term is deployed at a higher ratio of use to understanding. President George H. W. Bush was pilloried for his frequent refrain that a course of action wouldnt be prudent. The term connotes caution, to the point of timidity to some and cowardice to others. Yet this is to misunderstand prudence as a classical virtue, one for whose recovery contemporary politics aches. Genuine prudence entails what Burke called a moral rather than a complexional timidity. Prudence is cautious not out of fearwhat he also called a false, reptile prudencebut rather from a moral commitment to the limits of individual reason. At the same time, there are moments when prudence demands bold action and unbending tenacity. The key to prudence is knowing the difference, having the capacity of judgment that can distinguish between ordinary moments and genuine crises and, in either case, calibrating action to proper goals.

Burke and Lincoln are odd partners in such a conversation even if, as the Burke scholar Jesse Norman argues, Lincolns leadership was Burkean through and through. There is no evidence that Lincoln read Burke or was influenced by himNorman notes that there is, by contrast, ample evidence that Lincoln read Burkes rival Thomas Paineand the word prudence appears only a handful of times in Lincolns writings. Even then, he generally associated it with caution, as in his first annual message to Congress in December 1861, when he said he had enforced confiscation laws according to the dictates of prudence, as well as the obligations of law. While both men climbed from modest circumstances to the heights of statesmanship, Burke cut an elegant rhetorical path through some of the greatest controversies of his day. What Burke said of Marie Antoinettethat she hardly seemed to touch the earthmight be said of his prose. Lincoln, by contrast, was a rough-hewn backwoods lawyer whose mature rhetoric, while eloquent, is characterized by an unmistakable heaviness. Burke was a famed skeptic of the French dogma of universal human rights; Lincoln, like Burke an opponent of slavery, spoke frequently in the idiom of equality and liberty.

Next page