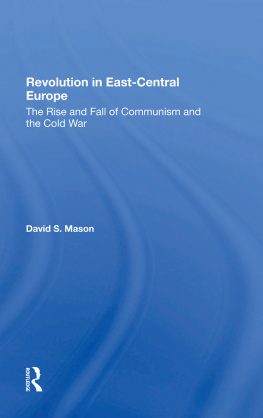

First published 1993 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1993 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hudelson, Richard.

The rise and fall of communism / Richard H. Hudelson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Communism--History--20th century. 2. Socialism--History-

20th century. I. Title.

HX40.H738 1993

335.430904dc20

92 - 35855

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29555-4 (hbk)

Writing this book has been a rewarding but challenging experience. Along the way I have had the helpful comments and criticisms of a number of friends and colleagues. Pat Maus, Susanna Frenkel, Kit Christensen, and Carl Ross read the entire manuscript. Steve Chilton, Milan Kovacovic, and Marina Rumyantseva read parts of it. They and the reviewers for Westview Press have weeded out many errors and forced me to think through a number of difficult points. The errors and confusions that remain do so in spite of their best efforts. I thank them all. I would also like to thank Spencer Carr of Westview Press for his support of this project and for his editorial suggestions, which resulted in major improvements. Finally, thanks to Jean Vileta for her editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript for publication.

This book deals with highly controversial material. The views expressed are my own. They rest on my thought and experience. The differing opinions of those whom I know to be honest and thoughtful readers have driven home to me the largeness of the issues and the limits of our thought.

Richard H. Hudelson

In this twentieth century we human beings have achieved both great and terrible things. Our technology dwarfs the achievements of the past. But our depravity, too, stands magnified by the increased powers at our disposal. Ours is the century of spaceflight and the century of the holocaust. Perhaps neither better nor worse than the human beings who have preceded us, nonetheless we cut a wider path.

Communism, the grand experiment that spans the century from near beginning to end, exhibits this same mixture of greatness and depravity. Rooted in a nineteenth-century dream of universal human emancipation, the communist cause called forth heroism and saintliness but also cruelty and servility. A history of communism would tell us much about the century we occupy and about ourselves as well.

For over a century, dreams of a better world inspired tens of thousands of human beings from around the globe to dedicate their lives to the cause of socialism. The experiment in communism, which began in Russia with the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, grew out of this broader international socialist movement. The dramatic collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union heralds the failure of this great experiment. But what does this failure mean? Does it prove that socialism cannot work? Does it show that the vision of universal human emancipation is a phantasm that we must now abandon? What are we to make of the rise and of the fall of communism?

These are the questions that lie behind this work. They are philosophical questions, but they are philosophical questions that cannot be addressed in the absence of some understanding of the historical process that gave rise to them. According to one popular conception, a philosophical wall separates the vision of communism from the vision of socialism. In fact, throughout the nineteenth century communism and socialism were pretty much synonymous terms. It was not until the split in the international socialist movement, following the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, that communism and socialism took on distinct meanings. From this point on communists were socialists who followed the ideas of the Bolshevik leader V. I. Lenin, and socialists were socialists who did not. At bottom, what separated communists and socialists was not so much distinct philosophical conceptions of the future society they aimed to create as differences about the steps necessary to reach this future society. To be sure, communist convictions about the steps necessary for constructing socialism significantly affected the version of socialism built in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, but for socialists and communists alike the ultimate goal was a society in which rational cooperation replaced marketplace competition as the governing principle of social life.

There are many who do see in the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union definite proof of the inevitable failure of all forms of socialism. But there are others who do not draw this conclusion. They argue that Soviet communism, which was widely copied in Eastern Europe, was a fundamentally flawed version of socialism. For them, the failure of Soviet communism does not prove the failure of all possible forms of socialism.

In order to think through this controversy, it is necessary to have some understanding of the particular version of socialism that was developed in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and of its relationship to the socialist tradition from which it grew. And to achieve this understanding, it is necessary to have some understanding of the historical choices that were made. Is the failure of the Soviet experiment due to perversions of Soviet socialism introduced by Joseph Stalin? Was the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, under the leadership of Lenin, from the beginning a betrayal of socialism, as many prominent socialists argued at the time? Or do the seeds of the failure of Soviet communism lie deeper, in the ideas of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels that came to dominate the socialist movement in the late nineteenth century? Can we find among pre-Marxist visions of socialism the model for a viable socialist future? None of these is simply a historical question, but none of them can be answered without a sense of the history from which it is drawn.

This work aims at providing an introductory history of the socialist movement. Although it was written with an eye to questions about the philosophical significance of the rise and fall of communism, it offers a straightforward historical account that should be of value to all who are not specialists in the field. Its subject matter is the course of the international socialist movement from its origins in the early nineteenth century to the present.

This said, several qualifications are in order. First, the reader will discover that American communism has received attention out of proportion to its significance in the worldwide communist movement. The only reason for this emphasis is that I am an American writing for an American audience.

Second, the reader should be clear that this work is not intended as a history of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union is a product of diverse historical forces of which the socialist movement is only one. There are even some historians who think that the socialist movement is largely irrelevant to understanding the history of the Soviet Union. Although I would not go so far as this, I would agree that other factors may have been more important than the socialist movement in shaping the Soviet experience. But it is only as an experiment in communism, a particular version of socialism, that the Soviet Union interests me here. In this work the central question is what the fall of Soviet communism means for the cause of socialism.