Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2022

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright David Renton 2022

David Renton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN: 9781914420177

Ebook ISBN: 9781914420184

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ Books Ltd

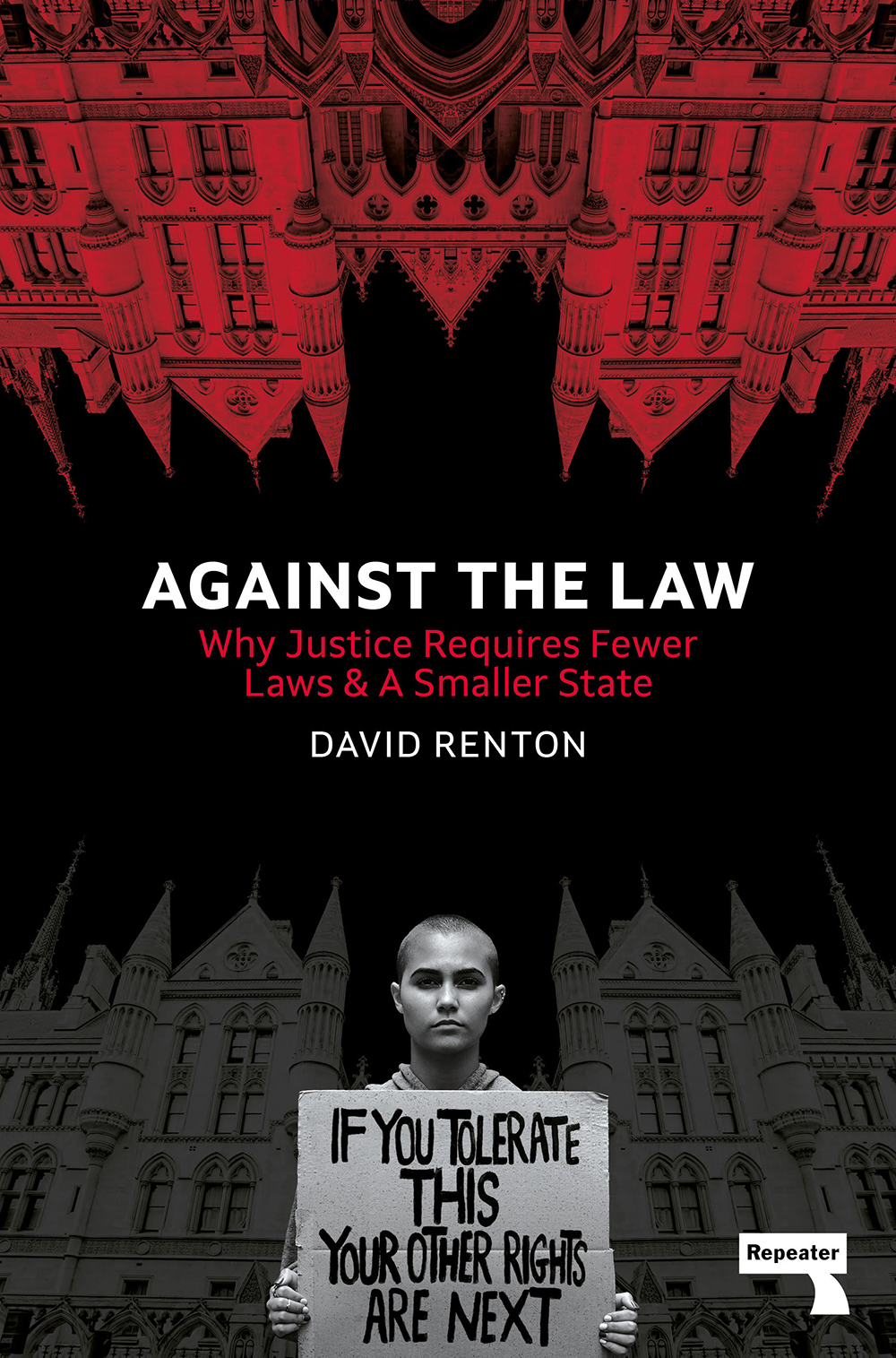

Meticulously researched and convincingly argued, Renton urges us to quit seeking liberation through legislation, instead wield our collective power for change.

G RIETJE B AARS , R EADER IN L AW AND S OCIAL C HANGE , C ITY U NIVERSITY

Rentons experience as a barrister and historian shines through in a learned, and eminently readable, account of the structure of law and the daily business of the Courts.

L IZ D AVIES , BARRISTER AND V ICE -P RESIDENT OF THE H ALDANE S OCIETY OF S OCIALIST L AWYERS

David Renton is one of the most consistently interesting and imaginative political writers in Britain today, and this eloquent attack on the repressive legalism common to populists and neoliberals alike is one of his best yet.

O WEN H ATHERLEY , AUTHOR OF R ED M ETROPOLIS

There are books that tell you what you already know, and books that challenge you to think bigger and better: Against the Law falls squarely with the latter. All police and prison abolitionists should read this book. It is a timely and sharp intervention, reminding us that laws are not only oppressively enforced but are themselves be a tool of control.

S HANICE O CTAVIA M C B EAN , ACTIVIST WITH S ISTERS U NCUT

A cogent, compelling argument that the pursuit of justice requires breaking with the hegemony of law.

P AUL OC ONNELL , R EADER IN L AW , SOAS

CONTENTS

Introduction

Legislative hyperactivity, complained Tom Bingham, the former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, has become a permanent feature of our governance.

Every year around 14,000 pages of new legislation are added to the statute book, including both primary legislation (meaning Acts of Parliament) and secondary legislation (such as Statutory Instruments in other words, supposedly noncontroversial laws made by ministers). This is double the volume of legislation of forty years ago. If we imagine a reader doing nothing other than reading new law and doing so at the rate of one page every ten minutes, working eight hours a day, five days a week and taking no holidays and breaks, thirteen months would be needed to read one years law. You would look up from your desk when you finished, and there would be more laws waiting to be read than there had been when you began.

This book has been written from the desire to see a more equal society and for the gap between the richest and the poorest to be narrowed or abolished. These ambitions cannot be fulfilled, this book argues, except in a different sort of society characterised by, amongst other things, fewer laws. Understanding why the law has grown is part of the process of preparing for that future society, as is explaining why attempts at simplifying the law have failed.

Why Should We Need Fewer Laws?

The idea of this book is to challenge how readers think about the law. Some readers will be wondering why a left-wing lawyer is calling for fewer laws. Ever since the neoliberal breakthrough in the 1970s, hasnt it been the right who have argued for the dismantling of the state? Arent laws the product of popular struggle; isnt it the case that every popular movement in history has gone into battle with the state, and left the traces of its conflict in rights to protect workers, women or Black or minority ethnic communities?

But laws have just as often emerged to tame insurgent forces as they have done to satisfy their demands. Take, for example, employment law. The modern Employment Tribunal system can be traced back to the Industrial Relations Act 1971, which gave Industrial Tribunals, as they were then called, the power to hear unfair dismissal claims. The Act was introduced by the Conservatives, not Labour. It was opposed by the trade unions. It was not passed as a result of workers raising their demands in ever increased volume until the state was obliged to recognise them. Rather, politicians sought to defeat a rising workers movement, and use the expansion of the law as one of a package of measures all intended to weaken that cause.

For more than forty years, employment law has been served by the presence of one main sourcebook, Butterworths Employment Law Handbook , which collects the most important primary and secondary legislation, as well as EU Directives and statutory Codes of Practice. Known to practitioners as the green book, most employment judges have a copy on their desk. If you attend a Tribunal hearing, you can expect the case to be disrupted at any moment as the lawyers open their books and check what the law says. The Employment Law Handbook was never a slim volume. Its first edition was 558 pages long on its publication on 6 March 1979, two months before Margaret Thatchers first general election victory. Since 1979, the weight of the books paper and its font size have shrunk. The sections on health and safety law have been reduced, and those on union rules cut to nothing. Despite those changes, by 2020 the Employment Law Handbook had swollen from under 600 to over 3,000 pages. Its weight has doubled to over 2kg, while its price has increased from 9.25 in 1979 to over 200 today. There was a time when it was usual for judges to take out their green books and slam them on the table to mark their disgust with an advocates poor explanation of their clients case. But that was a decade ago and longer. If a judge tried to lift the 2021 edition of Employment Law and wave it, you would be worried for the judges wrist and anxious for the table.

The growing complexity of the law has had an effect on social movements. Alongside the extension of individual rights, politicians introduced the most restrictive antistrike laws in Western Europe. Instead of workers responding to a dismissal by threatening industrial action, it is far more common for unions to threaten the employer with a potential Tribunal claim. For the employer, this threat carries a risk: Tribunals are slow, preparing for them is expensive and time-consuming, and if a worker wins their victory may be reported in the press. But seen from the perspective of the workers, median awards are derisory, just three to six months wages for both discrimination and unfair dismissal claims. Fewer than one in a thousand unfair dismissal claims result in an order for re-engagement or reinstatement. Under a legal system of resolving complaints, workers jobs have become less secure and their ability to protect their jobs weakened. Many trade unions have taught themselves to lower their ambitions, to give up all talk of workers control, and to reinvent themselves as legal insurance societies, relying on representing their members before judges rather than on their own self-activity.

Next page