Introduction

Former San Jose mayor Tom McEnery attended a meeting of the preeminent urban policy organization, the United States Conference of Mayors. The organizations Washington headquarters is adorned with a large picture of President Franklin Roosevelt and with framed correspondence describing his close relationship with the mayors of the great cities.

Late in the day, as yet another speaker droned on about the pressing need for increased federal assistance to the cities, says McEnery, the host, Mayor Marion Barry, finally showed up. Barry, dressed in the red warm-up suit he must have slept in, slumped into the chair next to [McEnery] and closed his eyes. McEnery goes on: Suddenly, Marion Barry came alive, interrupting the speaker [to] blurt out a few non sequiturs. Jaws dropped to the sound of nervous laughter, and the conferees gazed in disbelief as Barry rambled on. Finally, he slumped back into his chair beside McEnery, apparently satisfied that he had made his point. Politely, we all acted as if nothing happened, says McEnery. The speaker responded with, Excellent point, Marion. Now back on the subject of block grants. McEnery concludes, I have never shuffled my papers as intently as I did the rest of the meeting.

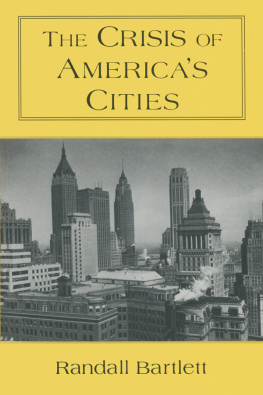

In a sense, what happened with Marion Barry at the U.S. Conference of Mayors meeting was not unusual. The leading lights of urban liberalism had been averting their eyes for decades. For thirty years the mayors had been defining the big city as a welter of woes whose ruin would be rewarded with financial aid from the federal government. When failure begat failure, the venerable U.S. Conference of Mayors, begun by the legendary mayors James Michael Curley of Boston and Fiorello La Guardia of New York, persisted in pursuing policies that presented the cities as the hopeless victims of racism and governmental neglect. These once great centers of commerce and innovation redefined themselves in terms of both their dependent populations and their fiscal dependence on Washington.

The upshot has been that the cities run along liberal lines have, like Marion Barry, fallen from public grace. Cities, says veteran analyst George Grier, have been gaining more problems than voters over the past three decades. Cities have become the symbols of government policy and society gone awry. Says Mayor Michael White of Cleveland, Big cities [became] a code name for a lot of things: for minorities, for crumbling neighborhoods, for crime, for everything that America has moved away from.

Once upon a time, big cities and their liberal ethos were at the very center of national political and economic life. Born in the big cities, modern liberalism eventually died there. It first emerged in the 1920s, a triumph of the urbane and the tolerant over the rural and the repressive, culminating in the 1933 repeal of prohibition. It came of age in FDRs 1936 landslide presidential victory, when the New Deal shifted from a rural to an urban base and big government became a permanent part of American life.

The big cities, which had successfully integrated the vast turn-of-the-century wave of immigrants, were at the heart of the coalition that remade America in the course of defeating both the Great Depression at home and dictators abroad. These are the glories former New York mayor David Dinkins spoke of when he defined the cities as the soul of the nation.

Confusing the past with the present, Dinkins, in the early 1990s, repeatedly asserted that like a mighty engine, urban America pulls all of America into the future. Former New York governor Mario Cuomo was unintentionally closer to the mark when he, evoking the era of Al Smith and FDR, noted poignantly that the future once happened here.

The political rise of the cities during the New Deal coincided with the end of a century of urban economic growth. The great cities of the Northeast and Midwest had been built on the conjuncture of rail and river, which centralized everything from manufacturing to merriment. A variety of new technologieselectricity, the internal combustion engine, the telephonehad begun to distribute the citys functions over a whole region, but as early as 1923, Frank Lloyd Wright saw that the big city is no longer modern.

In 1930 an Atlanta editor saw the future: When Mr. Henry Fordput some kind of automobile within easy reach of almost everybody, he inadvertently created a monster that has caused more trouble in the larger cities than bootleggers, speakeasies, and alley bandits. Long before race became the central issue in American politics, the automobile allowed middle-class whites to escape the clamor and congestion of the city, with its soot and saloons, for pastoral enclaves of their own. Whats more, those enclaves were subsidized by the same New Deal so beloved of urban liberals. In 1934 the Federal Housing Authority began to insure low-interest long-term mortgages for new suburban single-family housing construction.

Both people and jobs began leaving the cities. As early as the 1930s, city planners worried about what was then called blight as manufacturing, once organized around the railroads, moved to cheaper exurban land serviced by trucks. In some cities, such as Baltimore, the changes were astounding: between 1929 and 1939, notes the historian John Teaford, Baltimore lost 10 percent of its manufacturing while manufacturing in its metro area grew by 250 percent. The dispersal of manufacturing and jobs was only hastened by World War II, when decentralization was a matter of national security. By 1950, 23 percent of the population would be suburban; today it is 53 percent.

To make matters more difficult for the postwar cities, the mechanization of Southern agriculture sent vast numbers of Southern sharecroppers, semiliterates with few salable skills, streaming north into the cities. In the 1940s and 1950s, people who led economically isolated lives in the South were shunted, often for racist reasons, into the isolation of public housing. Had there been no racial mien to this migration, absorbing the newcomers would still have been difficultbut doable. After all, at the turn of the century, many had feared that the vast wave of new immigrants from the backward lands of southern and eastern Europe would be unassimilable, but in a celebrated triumph the cities proved to be the great incubators of ethnic integration; the factories, schools, and political clubs of the big cities turned immigrants into Americans. The postwar cities had a harder time integrating their newcomers. The changes in technology dealt them a bad hand, which they then played badly. But while economic decentralization was and still is a salient source of city woes, the problems plaguing cities are also the product of public policy choices produced in the 1960s, a period of extraordinary prosperity.

The current plight of the cities is linked to a series of gigantic public policy wagers made three decades ago in Washington, New York, and Los Angeles. Though now forgotten, the terms of the gambles made in the wake of the Watts riot in Los Angeles were simple enough, but the consequences have been complex and unnerving.

In the mid-1960s, urban policy makers, under the influence of a dizzying mix of guilt, fear, and hubris, decided that when it came to black and, to some extent, Hispanic America, the immigrant model of incorporation through acculturation was to be abandoned. The assumptions and institutions that allowed the newcomers from eastern and southern Europe to gain their rightful place in American life were, in the face of the riots of the sixties, to be not just modified but completely abandoned. Instead, hoping to remedy the wrongs of racial injustice, policy makers boldly decided to bet the national (or at least the urban) future on an entirely different and untested set of premises. New Deal-era assumptions about the close connection between work and well-being, the need for a common culture, and the importance of public order were cast aside as either racist or inadequate to the needs of the new arrivals.