Originally published in 2002 by Lidov Noviny Publishing House and the Robben Island Museum.

Published 2004 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2004 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2004046036

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fallen walls : prisoners of conscience in South Africa and Czechoslovakia / [compiled by] Jan K. Coetzee, Lynda Gilfillan, and Otakar Hulec ; with a foreword by Vclav Havel.

p. cm.

Originally published: [Czechoslovakia]: Nakladatelstv Lidov Noviny ; [Cape Town, South Africa] : Robben Island Museum, 2002, in series: Robben Island memory series.

Includes bibliogaphical references and index.

ISBN 0-7658-0229-5 (alk. paper)

1. Political prisonersSouth AfricaRobben Island. 2. Political prisonersCzechoslovakia. 3. Prisoners' writings, South African (English) 4. Prisoners' writings, Czech. I. Coetzee, Jan Karel. II. Gilfillan, Lynda, 1948- III. Hulec, Otakar.

HV9850.5.Z8R635 2004

365'.45'0922437dc22

2004046036

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0229-3 (hbk)

It is a universal quest to seek lessons from history. Unfortunately, however, the details of the past all too frequently remain unknown. Indeed, the voices of certain heroes of our recent history who fought against oppression are slowly fading, as the details of their lives slip from human memory.

This book contains six such life histories, those of three South African and three Czech prisoners of conscience. The stories of these six patriots who fought for democratic principles help to prevent the erosion of memory. By juxtaposing these seemingly separate yet shared destinies, the authors remind us anew of the price that is so often paid for freedom and democracy.

Vclav Havel,

Former President of the Czech Republic

War, conflict and oppression have always bedevilled human relations, and revenge and persecution form part of a continuous cycle of destruction. All too often, the coming together of people to form nations or ethnic or ideological groups is followed by fragmentation, as one group ranges itself against another for some or other reason. The very process of self-definition sets up the other against which the self, the nation, or the group is defined. And so the elements of conflict are set in place.

The pages of history are frequently bloody records of cruel campaigns, unjust systems, and attempts at the systematic elimination of those identified as the enemy, the other. We are masters of the art of designing brutal systems that we unleash on those we fear or despise. And the debris of wasted, twisted human lives surrounds us, whether we find ourselves in the gleaming affluence of the first world, or in the grim wastelands of disease-ridden developing nations. There was a time when the injustices inflicted upon ones adversaries could be kept out of the public eye, when many human rights violations remained obscure. But today the evidence and the anger are inescapable, whether in the shacklands of Sudan or South Africa or in the street battles that are fought over globalization at meetings of this centurys superpowers. The global village has never been as small, nor have the satellite images of CNN and Sky Television been as pervasive or persistent. But notwithstanding the media exposure of those proclaiming an alternative, individual voices are seldom heard in the fleeting media image and shallow sound bite. In a book such as this, however, the words that express the feelings, thoughts and daily experiences of victims of oppression give substance and resonance to the human suffering that continues to plague our times.

History is written by the victorious, and all too often the actual experiences of those nameless, faceless masses who are its subjects and its shapers, are silent, unsung. These pages open to public scrutiny the experience of those who have suffered one of the most extreme forms of human rights abuse: longterm political imprisonment. Each page speaks of the toll and trialsbut also the personal triumphsof incarceration. Resonating in each voice is the trauma of deprivation, the absence of all that invests human life with meaning and value: family, work, the comfort of the cherished and familiar. Life behind bars is not merely a form of cruel punishment, it also embodies an excruciating form of human degradation.

Long-term imprisonment is always the first resort of the totalitarian state when confronted with the dissident. As with the banishment and ostracism of other eras, the individual is cast into a state of inner desolation. Here, life is one of discontinuity, and a primary human needa sense of belongingis trampled on. The life-histories that unfold in these pages describe what it feels like to be taken from the familiar, daily rituals we develop to structure our lives, from networks of support, and from the comforting sense that one can move around freely, associate with whomever one chooses, and explore the larger world of images and ideas.

Long-term imprisonment inevitably leads to traumaboth in the lived reality of the individual, as well as the state of mind that results from disruption, and deprivation. Trauma can arise not only from a particular event, but also from a persistent social condition:

Something alien breaks in on you, smashing through whatever barriers your mind has set up as a line of defence. It invades you, possesses you, takes you over, becomes a dominating feature of your interior landscape, and in the process threatens to drain you and leave you empty. (Erikson in Rogers et al., 1999: 2)

The voices that are heard in the pages that follow give form and substance to this notion of trauma as it relates to the experiences of long-term political prisoners.

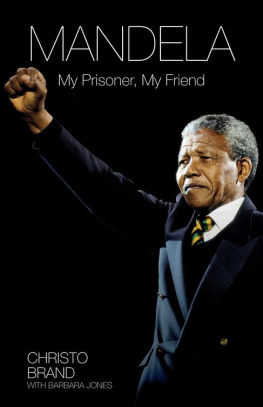

These stories focus on the individual experiences of a few of those who were at the receiving end of severe forms of political violence. At one end of a global, racial and ideological divide are three South Africansblack men from the southeastern part of a country whose white minority had in 1948 voted into power the Nationalist Party. Its legacy was that of apartheid. Joseph Mati, Johnson Mgabela and Monde Mkunqwana were among those who defied the system, and consequently spent the best years of their adult lives on Robben Islandhome of one of the worlds most notorious penal institutions. Unlike their famous leader, Nelson Mandela, these men were among the masses imprisoned in the anonymous general cells of the island prison. The Nationalist Party was not only racist, it was also deeply sexist. The patriarchal mind-set could not conceive of women political prisonersinstead, troublesome women were subjected to relentless harassment or, like Winnie Mandela, banished to alien, desolate rural areas.