Copyright 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abramson, Jeffrey B.

Minervas owl : the traditional of western political thought / Jeffrey Abramson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-03265-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-674-05702-9 (pbk.)

1. Political scienceHistory. I. Title.

JA81.A32 2009

320.01dc22 2008043390

For Jackie

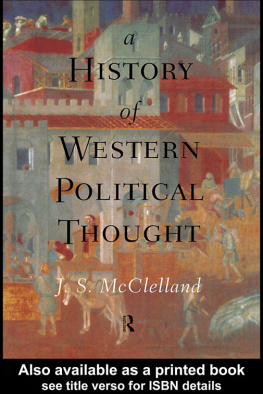

This book invites readers to join a conversation about politics, a very old conversation, going on for nearly 2,500 years now. It is not the only or the oldest conversation about politics, but it is a distinctly continuous and influential one.

The conversation begins over a particular historical event, the trial and execution of Socrates in 399 BC on charges of corrupting the young. Socrates execution caused one such corrupted youth, his pupil Plato, to detach himself sufficiently from the politics of the moment to stand outside events and judge them according to an ideal of justice that transcended the fiats of power. Without this moment of critical detachment, the conversation could not have begun. But it is equally the case that the conversationif it was to be a political conversationrequired engagement as well as detachment, a sense of allegiance or loyalty or attachment to a way of life worth criticizing.

Over time the conversation has left behind a set of canonical texts, which provide a common store of learning and reference. The texts constitute a canon, in the sense that later works offer commentaries on earlier ones. No one starts anew. A cumulative learning is passed on, but as it passes, it is changed, reinterpreted, and transformed without ever being overthrown or abandoned. Socrates taught Plato, who paid his teacher the compliment of writing almost always in the name of his mentor. So thoroughly did Plato inhabit the mind of his teacher that we cannot say for certain where the historical Socrates differs from the Socrates that Plato created. Aristotle in turn came to Athens to study at Platos school. He paid his teacher the different compliment of arguing with him. Aristotle tutored the young Alexander, but this did not stop the student from going on to conquer the Greek world.

Rome started as a republic but ended as an empire; along the way its greatest thinkers, from the slave Epictetus through the senator Cicero up to the emperor Marcus Aurelius, sought to revamp Greek ideas on justice to fit the morality of imperial ambition. Early Christians, such as Saint Augustine growing up in the provinces conquered by Rome, culled from Plato a doctrine henceforth known as Neo-Platonism that became Christianitys retort to the earthly justice of Rome, pallid in comparison to the heavenly justice of Gods city.

Islamic scholars of the ninth and tenth centuries recovered the lost works of the canon, translating the Greek classics into Arabic and beginning the tradition of commentaries on the works of Plato and Aristotle. It was through these translations that classical political philosophy became known to medieval Jewish scholars living under Islamic rule. The canon next worked its way back to Christian Europe by way of these Hebrew and Arabic translations. In different but parallel ways, scholars working within their own religious communities grappled with the implications of Greek rationalism for the truths of divine revelation.

In secular form the canon was revived with new purpose by Machiavelli during the Italian Renaissance, as he returned to the classics and the history of Rome in search of fresh ideas for restoring to Italy the lost glory that was the Roman republic. Machiavellis theory of republicanism became a bridge connecting the ancients and the moderns. In the tumultuous decades from the English Civil War to the Glorious Revolution, philosophers such as Hobbes and Locke used the canon to fashion new ideas about the origins and legitimacy of government. In time these ideas became the intellectual and political basis of liberalism and constitutional government; the American Declaration of Independence literally lifted its most soaring phrase about the right to revolution from the pages of Locke.

Liberalism brought in its wake both a conservative and a radical response. The radical critique began in France, where Rousseau seized on the ideas of Hobbes and Locke to push liberalism in a far more egalitarian directiona direction that, for a time, the French Revolution followed before collapsing into terror. The fate of the Revolution in turn provoked the classic conservative response given by Edmund Burke, a critique that in some ways returns to Aristotle for core arguments about the limits of political change and about the distinctive importance of custom, tradition, and the familiar to political life.

Kant found in Rousseaus notion of the general will a basis for his own, more systematic arguments about human freedom and equality. But both intellectually and politically, liberal doctrines took a different course in Germany, as Hegel commented on Kant, and Marx commented on Hegel. In ways that proved lasting, Marx purposely sought to put a stop to the conversation I am describing, rejecting the idea that there ever is anything distinctly political to talk about at all, and seeking to translate political concepts into underlying material realities driving the production of ideas. The Marxist rejection of political theory as ideological gave rise to modern sociology, and it is only in the last generation or so, with the restorative work on justice by John Rawls, that political theory once again stands at the center of a liberal arts education.

This book is based on introductory lectures on political theory that I have been giving over the past twenty-five years. Until now I have never sought to write those lectures down. I do so here, persuaded that they may be of use to the continuing student in all of us. The canon of political thought presents us, as one of my teachers used to say, with political arguments as enduring and eternal as such arguments possibly can be. For someone reading the texts for the first time, they are an awakening to why politics matter, just how much is at stake. But even for the politically active, they remain a place to revisit for inspiration and instruction. The arguments, after all, do not go away with political experience; they are more likely to come home to roost.

My hope is that this book will help make the great classics of political theory accessible to the general reader, as they ought to be. Political theory is not a specialty; it confronts us with the actual dilemmas of political life. To the end of engaging the reader in the political arguments going on, I adopt an informal, almost conversational tone. In particular, I pause frequently and fondly to reflect on my own teachers and students, the better to capture the sense that we are engaged in a dialogue not unlike that which takes place in the classroom.

I do not cover the entire history of political thought in this book. The selection I makea selection more recognizable than idiosyncraticis meant to isolate and illumine the core contrast between ancient Greek and modern political theory. It comes as a deeply surprising and jarring realization that some of the most brilliant minds of antiquity did not share our basic convictions about human nature, equality, and democracy. Aristotle confronts us with notions of a natural aristocracy in the human condition; Plato argues that the state should censor art. Together they disdain the private and economic life and would make the domain of politics all-encompassing rather than limited, as we today are wont to do.