Pakistan: 1995

Published in cooperation with the American Institute of Pakistan Studies

First published 1995 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe

Library of Congress ISSN: 1061-6101

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-28213-4 (hbk)

Contents

Rasul Bakhsh Rais

Charles H. Kennedy

Shafik H. Hashmi

Anita M. Weiss

Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr

Tayyab Mahmud

Samina Ahmed

Stanley A. Kochanek

Devin T. Hagerty

Ata Khan

Pakistan: 1995 is the second volume of a series of biennial assessments of contemporary events and issues in Pakistan affairs published by Westview Press in affiliation with the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. The first volume in this series was Charles H. Kennedy, ed., Pakistan: 1992 (1993). In general this series covers issues relevant to Pakistans domestic politics, foreign policy, and economy. Pakistan: 1995 also examines issues relevant to ethnic conflict, the status of women, the military, Islamization, the judiciary, privatization policy, and nuclear issues. Each of the contributors to this volume is a specialist on Pakistan, and each has had recent research experience in the state relevant to their respective contribution.

The American Institute of Pakistan Studies (AIPS) is a non-profit, tax-exempt, non-partisan educational organization and a member of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers. AIPS was founded in 1973; its mission is to encourage and support research on issues relevant to Pakistan and to promote exchange between the United States and Pakistan. To fulfill this mission, AIPS provides research fellowships to American and Pakistani researchers, administers lectureships, and sponsors academic conferences.

It should be noted that earlier versions of several of the chapters in this volume were presented at the Politics of Social Change in Pakistan Conference held at Columbia University, March 28-29, 1994, (). Special thanks are owed to the respective organizers of these conferences: Rasul B. Rais, then-Quaid-i-Azam Professor, Columbia University; and Omar Noman, Director, International Development Centre, Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford University. Financial assistance for the final production of Pakistan: 1995 was provided by the Research and Publication Fund of the Graduate School of Wake Forest University.

The co-editors would like to gratefully acknowledge the support and encouragement of Susan McEachern and her colleagues at Westview Press, who kept us focused on the final product.

Closer to home, I wish to thank Elide Vargas, the administrative assistant of the Department of Politics, and Megan Reif, my student assistant, for their efforts with regard to this project. Very special thanks are owed to Shannon Poe-Kennedy, who copy-edited various versions of the manuscript, and to Patricia Poe, who coaxed the recalcitrant manuscript into its final form.

Charles H. Kennedy

Wake Forest University

American Institute of Pakistan Studies

.

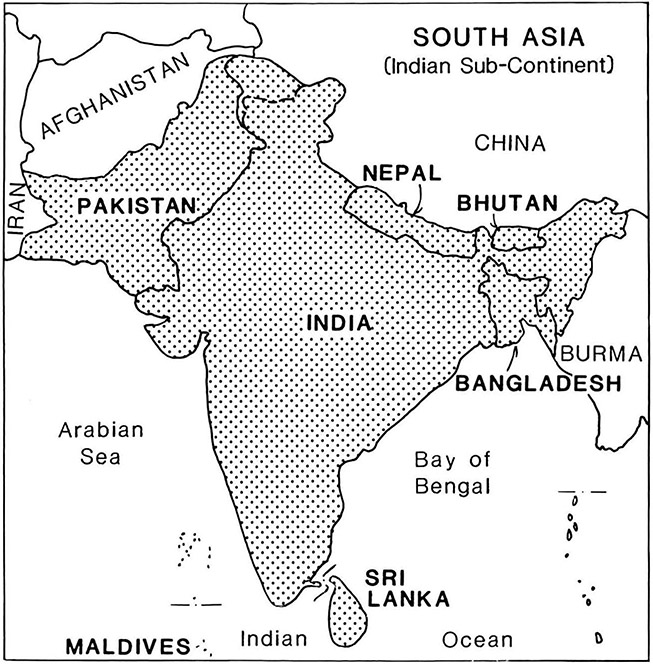

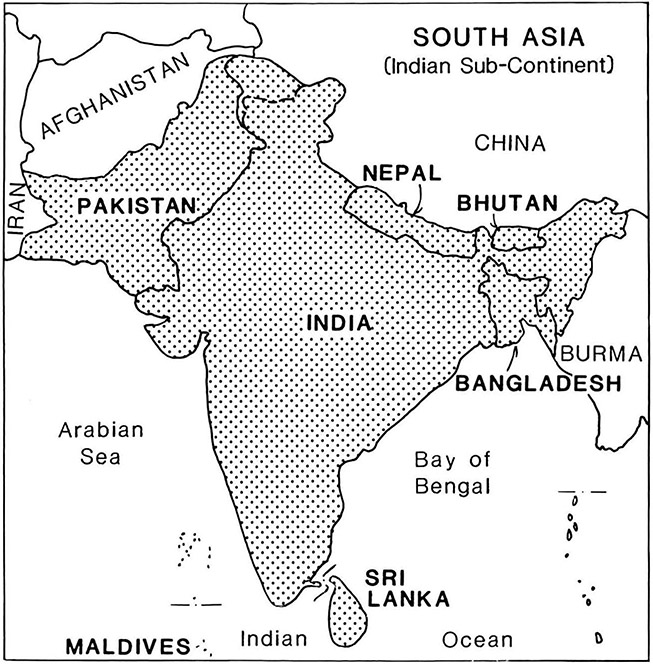

Source: Ashok K. Dutt and M. Margaret Geib, Allas of South Asia (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987).

.

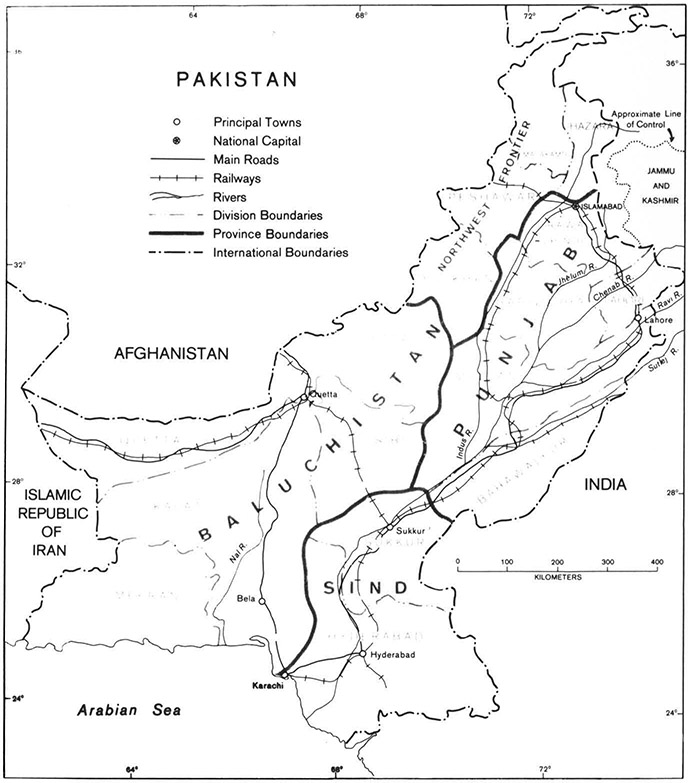

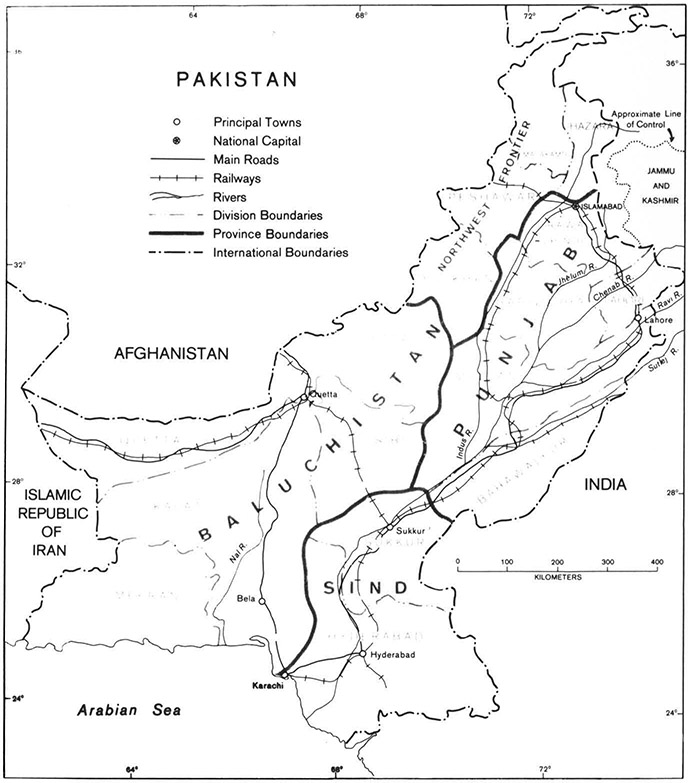

Source: Shahid Javed Burki, Pakistan: The Continuing Search for Nationhood (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991).

1

Benazirs Return to Power, 19921994

Rasul Bakhsh Rais

The problems of democratic transition which the country has been experiencing in recent years flow as much from the legacy of military rule as they do from a feudal political culture and an underdeveloped civil society that cannot fully support the functioning of a democratic polity. As the models of relatively advanced democracies suggest, the growth of a democratic order depends on the presence of freely competing political parties, the recognized supremacy of representative institutions, the protection of basic civil rights and liberties, and the observance of constitutional norms. Clearly none of these could flourish under the previous authoritarian regimes of Pakistan. With little or no political legitimacy, such regimes found it necessary to undermine systematically the development of such practices and institutions; often by suspending, distorting, or abrogating constitutions and by suborning or oppressing democratic movements and leaders.

But sadly, neither have the elected civilian leaders set any true democratic standards. Time and time again, they have demonstrated by their conduct that democratic principles are expendable, and what matters more is grabbing power, even by working through constitutional coups. Since the political atmosphere of Pakistan has remained highly polarized and the electoral mandates in the past three elections have been divided between the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the Muslim League, led by Nawaz Sharif (PML(N)); the two parties have become locked in a politics of confrontation. However, polarization that periodically escalates to intense political confrontation is merely symptomatic of much deeper crises of the Pakistani stateconstant decay of political institutions, erosion of the capacity of the state to govern, and the widening gap between popular expectations and ability of the state to live up to them. To complicate the crisis further, the civilian leaders from both sides of the main political divide have opted for confrontation as a strategy of political mobilization. An overview of political developments during the past few years would suggest that the democratic transition remains highly tenuous and incomplete.

Fall of the IJI Regime

The convincing electoral victory of the IJI (Islami Jamhoori Ittehad-Islamic Democratic Alliance) coalition in 1990 had raised the hope that Pakistan was entering a new era of stability. The IJI, by winning 106 seats in the National Assembly, did far better than its rival, the PPP, able to capture only 45. The IJI was also able to form coalition governments in the provinces. Unlike the PPP, the IJI leaders proved adept at striking effective political alliances with parties that had quite opposite ideological leanings. The political groups that felt victimized, left out by the PPP, or disgruntled with its style of governance were eager to give a helping hand to Nawaz Sharif. On the anvil of the 1990 elections, this congregation of anti-PPP political forces with opposing views on national issues, evidencing no common agenda for the future except common grievances and antipathy toward the party, was quite expedient. They shared only a negative interest in defeating the PPP, which made the IJI coalition vulnerable to defections from its ranks and later manipulation by the president.