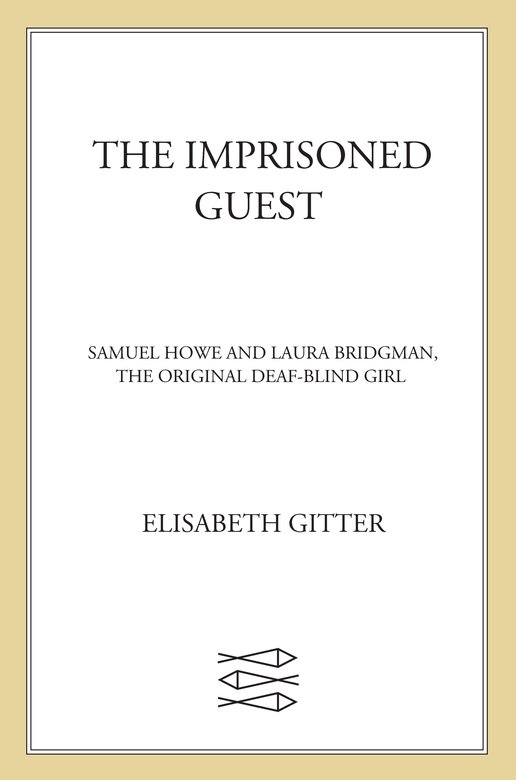

MY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS MUST begin with the librarians whose patience and skill made my research possible: Kenneth Stuckey and his successor, June Tulikangas, of the Perkins School for the Blind; Danielle Kovacs, Special Collections Librarian at Framingham State College; and the librarians and curators of the Harvard Houghton Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Brown University Manuscripts Library, and the Chapin Library of Rare Books at Williams College. I thank these institutions for permission to quote from material in their collections. As always, I am indebted to the John Jay College librarians for their dedication and resourcefulness.

At the Wayland Historical Society, I was fortunate to enlist the help of Helen Emery and Jo Goeselt, both expert historical sleuths. Campbell Waterhouse of the Duxbury Historical Society not only provided me with information on the Drew and Morton families, but also put me in touch with Susan Basile and Lydia Drews great-grandson, Lloyd Morton, who were willing to share handed-down stories about Laura. Frank J. Barrett, Jr., the author of a pictorial history of Hanover, New Hampshire, kindly filled me in on town geography. I thank Rian Keating, Hanoverian, thespian, and former student, for finding Lauras grave. Virginia Licklider and Ragnhild Bairnsfather provided me with able researchassistance in Boston. I am grateful also to Marilyn Christie, a gifted and enthusiastic genealogist who tracked down information in New Hampshire that I might otherwise never have discovered.

Many colleagues, friends, and generous scholars responded to my questions, read and commented on chapters, and offered ideas. Among those who will recognize their contributions are Michael Blitz, Paul Brenner, Richard Brodhead, Sheila Colon, J. Roderick Davis, Janice Dunham, Eli Faber, John Glavin, Jay and Judy Greenfield, Susan Har-tung, Betsy Hegeman, Jacqueline Jaffe, Karen Kaplowitz, Sondra Lef-toff, Patricia Licklider, Gerald Markowitz, Adrienne Munich, Jane Mushabac, Eric Nelson, Jill Norgren, Barbara Odabashian, Juana Ponce de Leon, David Rosner, Frederik and Judith Rusch, Shirley Sarna, Susan Schlechter, Linda Schrank, Dennis Sherman, Gillian Silverman, Anthony Simpson, Benjamin Smith, Dian Smith, Neil Smith, Garrett Stewart, and Mark Taylor.

My thanks to Suzanne Cohn for wise counsel; to Marc Dolan for always understanding my questions (and knowing the answers); to John Pittman for keeping me on course philosophically; to Catherine Kudlick for teaching me about the history of the blind; and to Robert Crozier for making work fun. For their psychological insights into Laura, I am indebted to Dr. John McDevitt, Dr. Katherine Dalsimer, and Dr. Kathy Berkman.

I thank Terry Pristin for introducing me to Eric Wensberg, who gave me the confidence to tell Lauras story. Through Terry, I also met my agent, the irrepressible Molly Friedrich. Rebecca Saletan, my editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, knew just where my manuscript needed strengthening; I was fortunate to have her and Katrin Wilde guiding me.

Without Carol Gronemans example and warm encouragement, I never would have embarked on this project. As I wrote, Anya Taylors voice, curious and exacting, was always in my head. She read each chapter, sometimes in several drafts, and her questions, objections, and proddings shaped my thinking. Infelicitous phrases seldom escape Karen Wunschs eye, and I thank her for her careful reading of my manuscript.

Authors are often grateful to their families simply for leaving themalone to write, but in my case the debts are more substantial. My parents, Joseph and Anna Gesmer, not only provided me with all the comforts of home while I did my Boston research, but also heartened me by their interest in Laura. I am lucky to have two children, Emily and Michael Gitter, who are accomplished writers. Emily showed me the way out of several blind alleys and advised me on troublesome passages; Michael, from a greater distance, patiently talked me through attacks of computer panic. Above all, I thank Max Gitter, whose clear, lively prose is the mark I always shoot for. He commented incisively on every chapter, helping me to untangle my thoughts. In writing this book, as in many endeavors, I counted on him.

Passing

FORGOTTEN EVEN WHILE she lived, Laura has vanished from public memory, eclipsed by Helen Keller. Pretty, self-sacrificing, cheerful, and good, Keller made a far more convincing sentimental icon than Laura ever had.

But Keller was not just a cardboard Victorian angel; she was a twentieth-century New Woman, too. She mastered French, German, Latin, and Greek; read Roman history, German philosophy, and English literature; graduated from Radcliffe College; wrote numerous books and articles; traveled around the world; and worked indefatigably for humanitarian causes. When she needed money, she earned it by writing, lecturing, and even appearing with Anne Sullivan on the vaudeville stage. A suffragist, pacifist, Swedenborgian, and radical socialist, Keller was not afraid to embrace unpopular ideas, although she usually did so sweetly.

She built her public identity on the assertion that for her anything was possible. At her college graduation, echoing Howes maxim that obstacles are things to overcome, she proclaimed, I grow stronger in the conviction that there is nothing good or right we cannot accomplish if we have the will to strive . The doors of the bright world are flung open before me and a light shines upon me, the light kindled by thethought that there is something for me to do beyond the threshold.

Her fierce determinationand phenomenal memory for the words and phrases that Sullivan continuously poured into her mindallowed Keller to become the best deaf writer of English in history. Although people who lose their hearing in early childhood seldom get a feel for the rhythms of spoken language, Keller developed a remarkable ear for English. As the poet Donald Davie has written in To Helen Keller, she became, by force of her afflictions, the most literary person ever was:

No sight nor sound for you was more than a ghost;

and yet because you called each phantoms name,

tame to your paddock chords and colours came.

Of course, Keller had editorial help for some of her books, but even in her personal letters, she composed graceful, lively, imaginative prose. The Story of My Life outsold and outlasted Laura Bridgman: Dr. Howes Famous Pupil and What He Taught Her not only because Keller had a more moving and dramatic story to tell, but also because she was a better writer than Howes daughters.

After Mary Swift Lamson told her of a deaf-blind Norwegian girl who was learning speech, Keller resolved that she, too, would strive to talk like other people, so that she could enjoy the sweet companionship of those from whom she would otherwise be cut off. Keller spent years training her voice, but speech proved to be the one obstacle that she could not pretend to overcome. For her, speaking intelligibly was a never-ending, self-punishing struggle, requiring an hour and a half of practice every day of her life.

According to one listener, Kellers voice always sounded like that of a Pythoness. Maud Howe Elliott thought it was the loneliest sound she had ever heard, like waves breaking on some lonely desert island; Thomas Edison said it reminded him of a steam exploding.

Despite her unnatural voice, Kellers impersonation of a hearing, sighted person was convincing enough to be inspiring rather than absurd. Her glass eyes looked almost real. In company, she kept an attentive, pleasant smile on her face, as if she could hear what was going on. Before public performances, she practiced her speeches over and over until they were intelligible. To prove that she could enjoy normal pleasures, she made a great show of appreciating music, art, and nature. And almost always, she maintained that she was deeply happyat least as happy as anyone else. The gladdest laborer in the vineyard may be a cripple, she insisted.