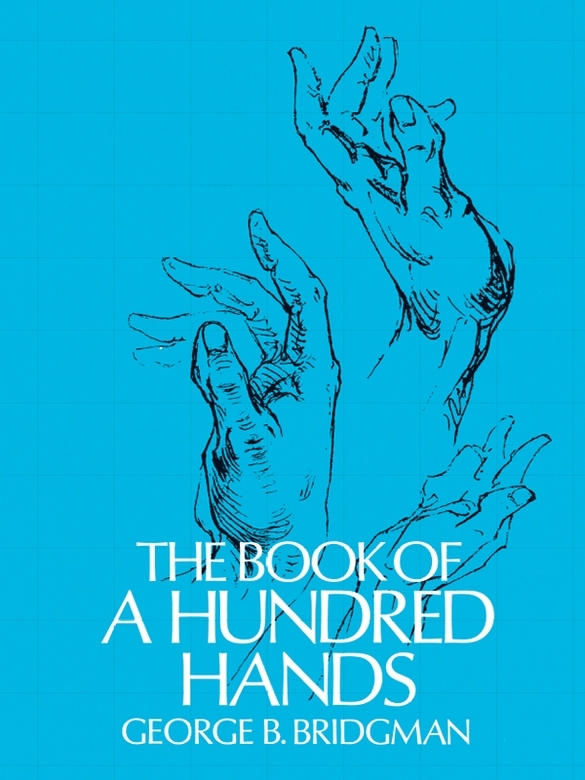

George B. Bridgman - The Book of a Hundred Hands

Here you can read online George B. Bridgman - The Book of a Hundred Hands full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Book of a Hundred Hands

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Book of a Hundred Hands: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Book of a Hundred Hands" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Book of a Hundred Hands — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Book of a Hundred Hands" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE AUTHOR desires to acknowledge his indebtedness to Dr. Ernest E. Tucker as his collaborator in the preparation of this volume.

G. B. B.

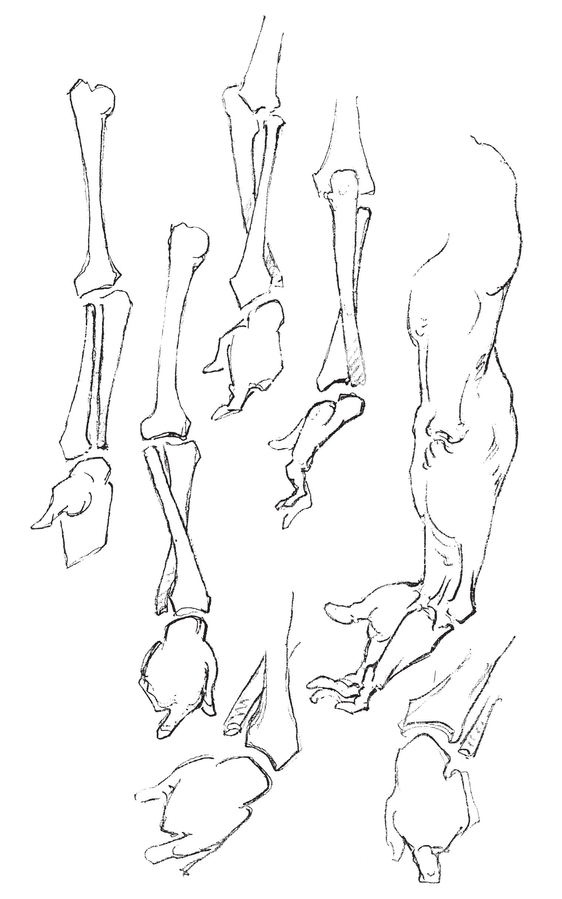

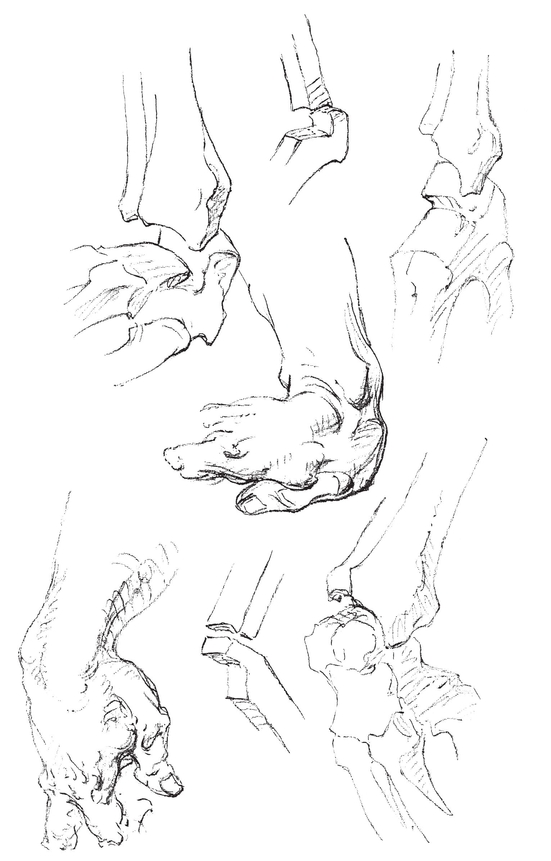

From practically the same foundation grew on the hind leg a foot, and on the fore limb a hand. The foot, standardized to conditions of pressure, has massive bones with short toes and huge heel; has arches, columns, etc.

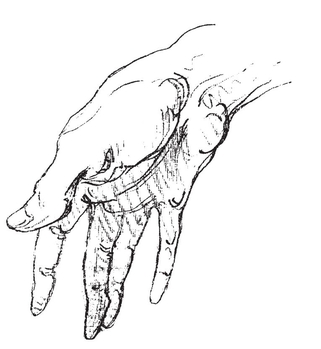

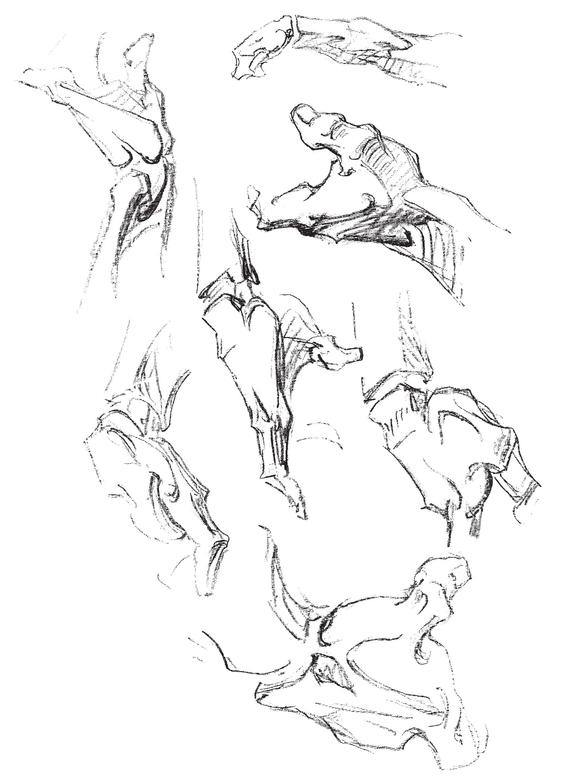

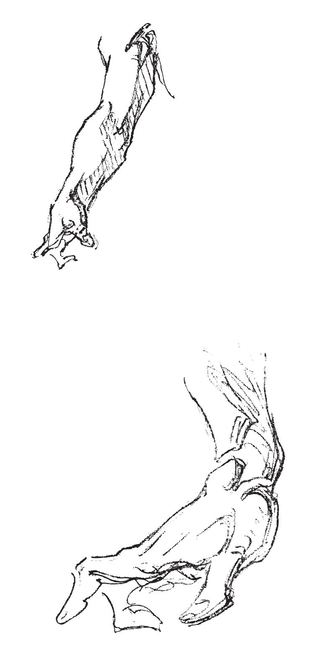

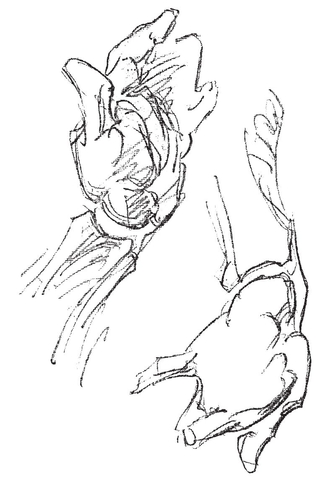

In the hand the determining factors were suspension or clasping, and movement. As the mechanics requires, the bones are long and slender, the fingers are long and flexible, with suspensory tendons running their length inside (i. e., next the object clasped) ; and the strong opposing thumb is warped around forward to complete the circle. The heel of the hand is negligible. The wrist is tapering, to allow freedom of movement.

The line of tension from the arm passes through the radius, to the wrist, thence in straight line to the middle finger which is therefore the largest.

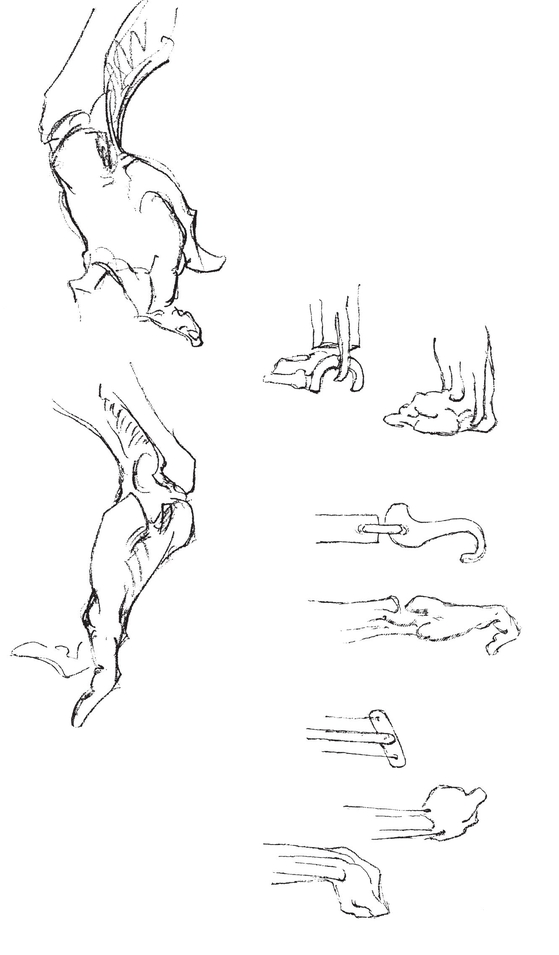

The thumb is warped around to the front corner of the wrist, covering at its base practically all of the side, and half of the frontthe space opposite the bases of the first two fingersand overlapping with its muscles the base of the third. Its attachment, in other words, is opposite the radius. It sweeps across the first three fingers.

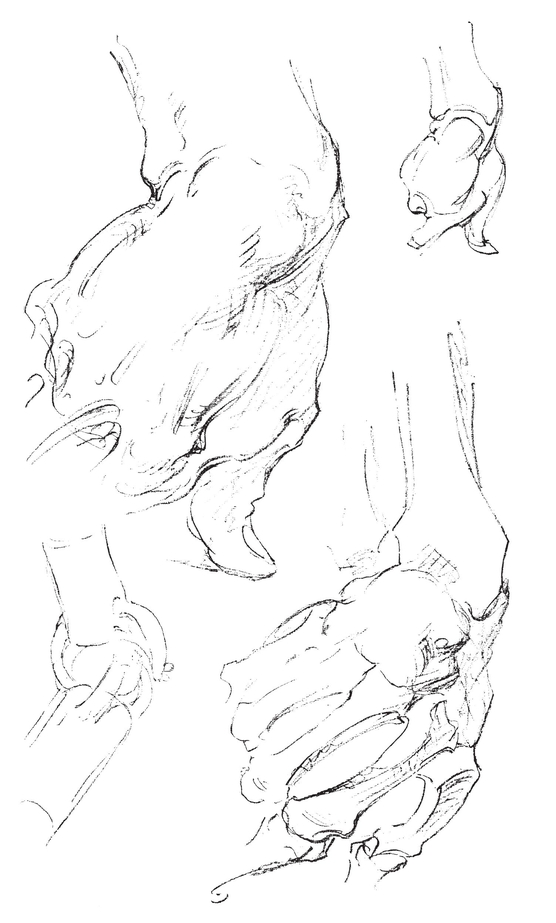

The carpal bones are deeply arched backward across the wrist. This is to allow the flexor tendons to pass as near as possible to the point of least movement, in turning movements. Thus, in turning when the hand is clasped, there is little if any change of tension produced in these muscles by it.

From this point diverge the tendons to the fingers. This point is therefore the centre of symmetry for the fingers. From it they radiate; around it the knuckles, rows of joints and finger tips form concentric arches; and when bent, the fingers form transverse arches. The centre of these arches is slightly drawn toward the base of the thumb by its power, and the finger arches are somewhat altered by crowding.

The ends of this wrist arch are its pillarsthe trapezium under the thumb, the pisiform under the little finger side. The arch is a little higher and broader under the thumb, on account of the greater power applied there.

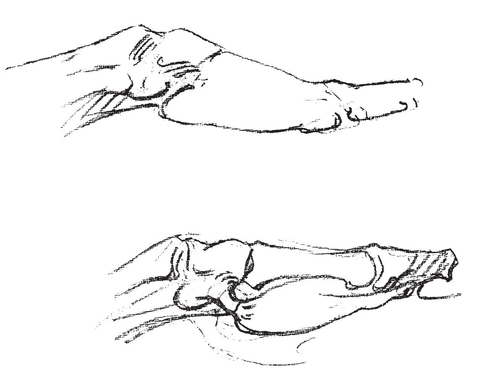

At the four corners of the wrist are attached muscles. But as the wrist bends back in clasping, the bases of the first and second fingers at the back are brought into more direct line with the tension ; wherefore the muscle of this corner is doubled, and the bones are larger.

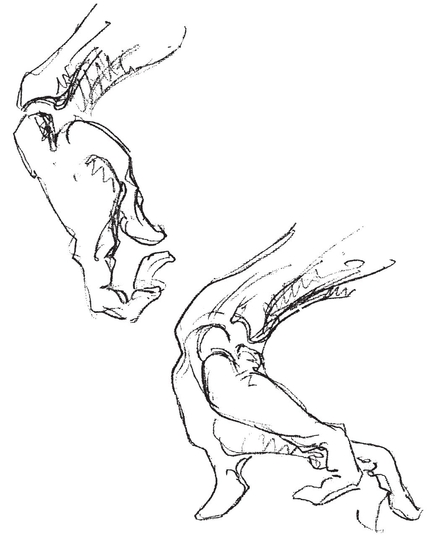

As the hand in clasping bends back and the thumb forward, the bones of the wrist adapt themselves. The bones of the second layer bend with the hand; those of the first layer remain straight with the wrist, although those under the thumb of both layers curve around with it.

Between these two layers is therefore an angle; it is seen in profile as a hook, pointing upward at the back. In extension (as in clasping), the radius is straight against the end of the hook. With the hand straight it is against a corner of it, leaving a step-down over the hook to the back of the hand. In flexion, the end of the hook seems to add itself to the end of the radius, making a long convex curve to the hollow of the hook, beyond which is the mound of the metacarpals, and beyond that again the somewhat hollowed sweep to the knuckles.

The wrist attaches to the radius, and therefore this hook, with the prominent metacarpals, is opposite the end of the radiusthat is, a trifle to the thumb side. They become a ridge which turns slightly to follow the direction of the hand.

In its warping around, the thumb is not brought to face the hand, but faces across the palm; in position to bind down the ends of the finger in clasping. Being on the radial side, yet drawn toward the mid line in traction, it makes the hand as a whole bend more easily to the little finger or ulnar side. Being in front, it causes the hand to bend more easily backward.

Turning movement as distinguished from rotary movement (flexion to each corner in rotation) is not present in the wrist, but is produced by the radius or turning bone of the forearm. Movement in the wrist is confined to flexion and extension (about one right angle) and side-bending (a little more than half a right angle, in the average hand) ; these two combined produce some rotary movement.

In movements of the wrist to extreme positions, the hand and fingers almost always participate, on account of association of tendons and muscular action ; and in these positions it is practically always separation and hooking of the fingers that is produced.

The movement of the hand reflects itself as far as the shoulder, through the biceps muscle, which aids in turning the radius. In all movement but turning, the wrist can act alone. Turning, to nearly two right angles, is carried out by the radius. Further movement of any kind must be performed by elbow or shoulder.

At the elbow it is the hinge movement that is important, wherefore the large size of the ulna or hinge bone, and the small size of the radius. At the wrist it is the turning movement that is important, wherefore the radius forms two-thirds of the joint, the ulna one-third.

The two pillars of the wrist clasp the tendons almost like hooked fingers and thumb. The opening is closed by strong fascia into a ring through which these tendons pass. They are deeply placed so as to be as near as possible to the neutral point in turning the wrist, making unnecessary a readjustment of tension to the fingers when the wrist turns.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

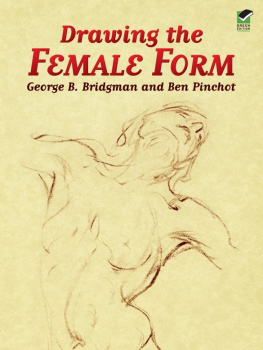

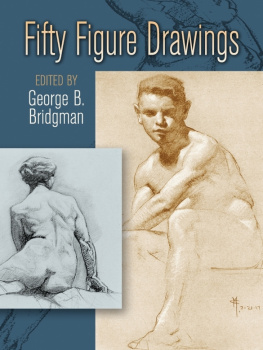

Similar books «The Book of a Hundred Hands»

Look at similar books to The Book of a Hundred Hands. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Book of a Hundred Hands and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.