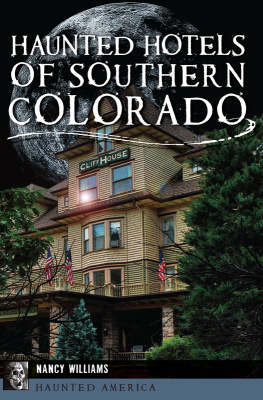

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Nancy K. Williams

All rights reserved

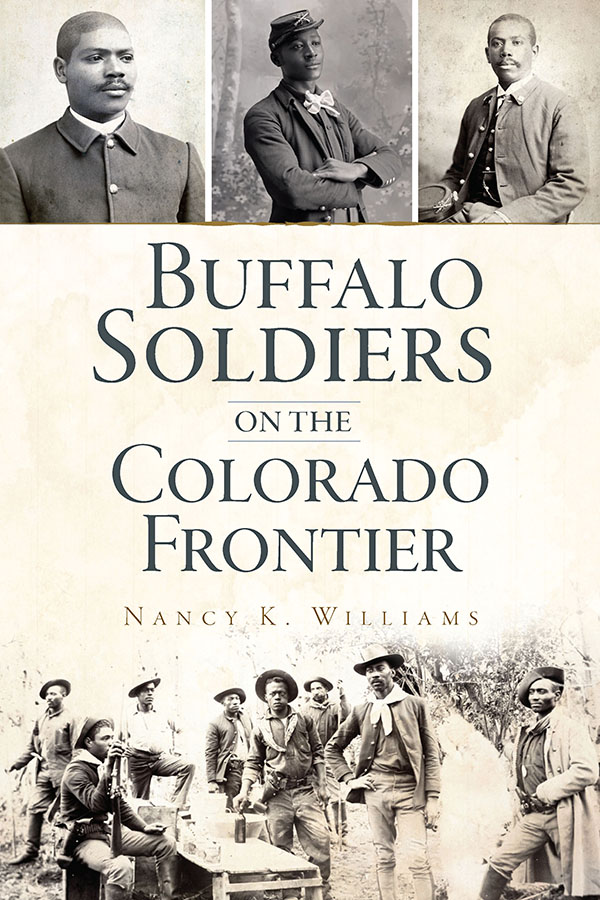

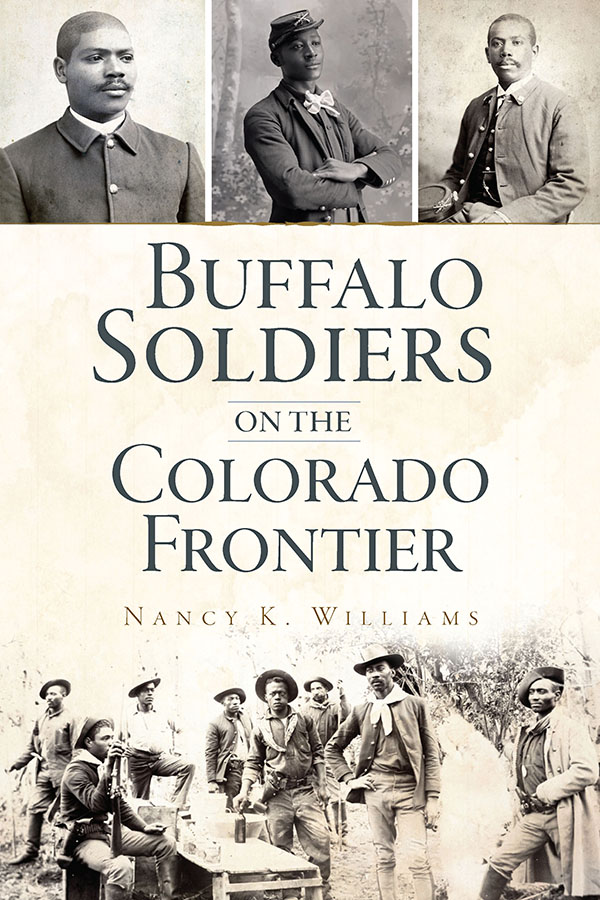

Front cover, top left: Buffalo Soldier. National Archives. Front cover, top right: Buffalo Soldier, Twenty-Fifth Infantry. National Museum of African American History. Front cover, center: Private William Cobbs, Twenty-Fourth Infantry, Colorado, 1894. History Colorado. Front cover, bottom: Tenth Cavalry, Montana, 1896. Montana Historical Society.

First published 2021

E-Book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.4396.7224.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020951674

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.4671.4544.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to the memory of Tommy.

Goodbyes are not forever.

If the muse were mine to tempt it

And my feeble voice were strong

If my tongue were turned to measures,

I would sing a stirring song.

I would sing a song heroic

Of those noble sons of Ham,

Of the gallant colored soldiers

Who fought for Uncle Sam!

Paul Laurence Dunbar, The Colored Soldiers, 1894

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Though volumes have been written about the Indian Wars and the settlement of the postCivil War West, the great majority of them overlook the service of the Black troops, the Buffalo Soldiers. There is scant mention in books by well-known historians like George Bird Grinnell in The Fighting Cheyennes or Robert Utley in Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indians, 18661891. In 1967, William Leckie published The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Black Cavalry in the West, which created the first interest in the Black troops. However, Leckie focused on the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries and their pursuit of Native Americans in Texas and the Southwest. There was little written about the Black infantrymen until Monroe Billington wrote The Buffalo Soldiers of New Mexico: 18661900. There are no books about the conflicts of the Buffalo Soldiers with the Utes in the Rocky Mountains or their fierce battles with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux on the plains of Colorado.

Much appreciation goes to the regional historical societies and librarians for information about the Buffalo Soldiers who served in their areas. Their collections of bullets, arrowheads, cavalry buttons, and artifacts gathered at battle sites and abandoned villages are remnants of that turbulent time.

My thanks to History Colorado, the White River Museum in Meeker, the Ute Indian Museum, and the Fort Garland Museum.

Thank you to Tom Williams, whose skill with the camera captured the lonely battlefields where the ghosts of men who fought still linger.

A special thanks to Artie Crisp, senior acquisitions editor at The History Press.

INTRODUCTION

During his years enslaved, hed never been allowed to touch a gun, and now that he was a free man, this new Ninth Cavalry recruit had his own guns and was going out West, where hed be shootin Injuns. After the Civil War ended, he hadnt found work as a field hand or laborer because the boll weevil had chewed through the cotton crop, the fields had been destroyed by the Yankees, and the corn had withered in a drought. He needed work so hed have money for food and a place to live.

A second young Black man had been unsuccessful in finding any kind of job in the North, and he was living in a shanty town on the outskirts of Philadelphia. After the end of the war, so many Black people traveled north that the competition for work was fierce. His future looked bleak until he heard about the army and thought that might be an answer. He didnt rush to join but talked to the recruiter and learned that enlisted men would be taught to read and write. That decided it for him, and he made his mark, a big X, on the enlistment papers. Now all he had to think about was that horse he would learn to ride.

The third Black man was a Civil War veteran who was no longer welcome in the South, where hed been born into slavery. Hed run away from a plantation when the first Confederate volley started the Civil War and joined the First Infantry in New Orleans. Hed learned about war as he fought with other Black soldiers in the United States Colored Troops (USCT), one of 186,000 slaves and freedmen whod enlisted in the Union army. When the war ended, hed returned to the Reconstruction South to face the hatred and retaliation of angry, defeated Confederates. After being dragged out of his cabin one night and beaten by a gang, he fled to the army recruiter. He knew how to shoot a gun and fight, and he was welcomed into the Tenth Cavalry. Hed soon be going west, where hed fight Indians and chase outlaws.

These three young Black men had different stories, but they shared some things in common. Now that they were free, they needed to earn a living, they wanted to learn to read and write, and they wanted the opportunity to show that they could become good citizens. The Emancipation Proclamation and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment had freed enslaved Black people, but neither showed them how to survive with their new freedom. When the Civil War ended, there were about one million surviving soldiers as the army began rapid demobilization, sending battle-weary veterans home. Just one year after the end of the Civil War, the army had only 11,000 soldiers, just when it needed the largest peacetime military in history. Troops were essential to maintain law and order, supervise Reconstruction in the South, patrol the Mexican border for revolutionaries and outlaws, and deal with the Indian Problem in the West. Attacks by the Plains tribes were taking a huge toll on lives and property, hampering westward expansion, and slowing the nations growth. Congress appropriated barely enough cash to build additional forts, but the small, demobilized army didnt have enough soldiers to man these forts, patrol the vast prairies, or protect settlers and travelers.

To meet the acute need for troops, Congress passed the Army Organization Act, authorizing the formation of six all-Black regiments in July 1866 and providing an opportunity for former slaves and USCT veterans. In the army, a man would earn thirteen dollars a month, the same pay as a white soldier; plus food, clothes, and shelter were provided. This was an opportunity with the promise of a future.

Recruitment began quickly, units were formed, and training started. The young recruits swiftly became toughened soldiers, serving proudly in the West, pursuing the Comanches and Kiowa in Texas, and chasing outlaws and bandits along the Rio Grande. They fought Apaches in Arizona and New Mexico and subdued the Utes of Colorado. During the Indian Wars from 1861 to 1898, there were about 26,000 men in the army, with 12,500 Black soldiers fighting on the frontier. Of every 5 cavalrymen, 1 was Black, and 8 to 10 percent of the infantry soldiers were Black. In the West, the two Black cavalry regiments made up 20 percent of the mounted troops