Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2014, is an unabridged republication of The Colored Regulars in the United States Army, originally published by A.M.E. Book Concern, Philadelphia, in 1904.

International Standard Book Number

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-79477-8

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

78057001 2014

www.doverpublications.com

BUFFALO

SOLDIERS

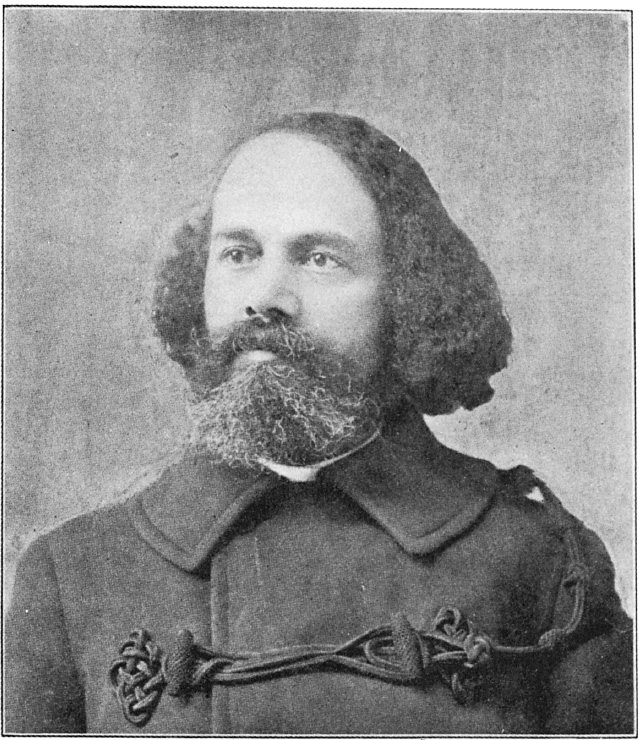

Chaplain T. G. Steward, D. D.

The Colored Regulars

In the United States Army

WITH A

Sketch of the History of the Colored American, and an Account of

His Services in the Wars of the Country, from the

Period of the Revolutionary War to 1899.

INTRODUCTORY LETTER FROM

Lieutenant-General Nelson A. Miles

Commanding the Army of the United States.

____

BY CHAPLAIN T. G. STEWARD, D.D.,

Twenty-fifth U. S. Infantry.

____

COPYRIGHTED 1904

____

PHILADELPHIA

A. M. E. BOOK CONCERN,

631 PINE STREET.

1904

INTRODUCTORY.

To write the history of the Negro race within that part of the western world known as the United States of America would be a task to which one might devote a life time and still fail in its satisfactory accomplishment. The difficulties lying in the way of collecting and unifying the material are very great; and that of detecting the inner life of the people much greater. Facts and dates are to history what color and proportion are to the painting. Employed by genius, color and form combine in a language that speaks to the soul, giving pleasure and instruction to the beholder; so the facts and dates occurring along the pathway of a people, when gathered and arranged by labor and care, assume a voice and a power which they have not otherwise. As these facts express the thoughts and feelings, and the growth, of a people, they become the language in which that people writes its history, and the work of the historian is to read and interpret this history for the benefit of his fellow men.

Borrowing a second illustration from the work of the artist, it may be said, that as nature reveals her secrets only to him whose soul is in deepest sympathy with her moods and movements, so a peoples history can be discovered only by one whose heart throbs in unison with those who have made the history. To write the history of any people successfully one must read it by the heart; and the best part of history, like the best part of the picture, must ever remain unexpressed. The artist sees more, and feels more than he is able to transfer to his canvas, however entrancing his presentation; and the historian sees and feels more than his brightest pages convey to his readers. Nothing less than a profound respect and love for humankind and a special attraction toward a particular people and age, can fit one to engage in so sublime a task as that of translating the history of a people into the language of common men.

The history of the American Negro differs very widely from that of any people whose life-story has been told; and when it shall come to be known and studied will open an entirely new view of experience. In it we shall be able to see what has never before been discovered in history; to wit: the absolute beginning of a people. Brought to these shores by the ship-load as freight, and sold as merchandise; entirely broken away from the tribes, races, or nations of their native land; recognized only, as, African slaves, and forbidden all movement looking toward organic life; deprived of even the right of family or of marriage, and corrupted in the most shameless manner by their powerful and licentious oppressorsit is from this heterogeneous protoplasm that the American Negro has been developed. The foundation from which he sprang had been laid by piecemeal as the slave ships made their annual deposits of cargoes brought from different points on the West Coast, and basely corrupted as is only too well known; yet out of it has grown, within less than three hundred years, an organic people. Grandfathers, and great-grandfathers are among them; and personal acquaintance is exceedingly wide. In the face of slavery and against its teaching and its power, overcoming the seduction of the master class, and the coarse and brutal corruptions of the baser overseer class, the African slave persistently strove to clothe himself with the habiliments of civilization, and so prepared himself for social organization that as soon as the hindrances were removed, this vast people almost immediately set themselves in families; and for over thirty years they have been busily engaged hunting up the lost roots of their family trees. We know the pit whence the Afro-American race was dug, the rock whence he was hewn; he was born here on this soil, from a people who in the classic language of the Hebrew prophet, could be described as, No People.

That there has been a majestic evolution quietly but rapidly going on in this mass, growing as it was both by natural development and by accretion, is plainly evident. Heterogeneous as were the fragments, by the aid of a common language and a common lot, and cruel yet partially civilizing control, the whole people were forced into a common outward form, and to a remarkable extent, into the same ways of thinking. The affinities within were really aided by the repulsions without, and when finally freed from slavery, for an ignorant and in-experienced people, they presented an astonishing spectacle of unity. Socially, politically and religiously, their power to work together showed itself little less than marvellous. The Afro-American, developing from this slave base, now directs great organizations of a religious character, and in comprehensive sweep invites to his co-operation the inhabitants of the isles of the sea and of far-off Africa. He is joining with the primitive, strong, hopeful and expanding races of Southern Africa, and is evidently preparing for a day that has not yet come.

The progress made thus far by the people is somewhat like that made by the young man who hires himself to a farmer and takes his pay in farming stock and utensils. He is thus acquiring the means to stock a farm, and the skill and experience necessary to its successful management at the same time. His career will not appear important, however, until the day shall arrive when he will set up for himself. The time spent on the farm of another was passed in comparative obscurity; but without it the more conspicuous period could never have followed. So, now, the American colored people are making history, but it is not of that kind that gains the attention of writers. Having no political organizations, governments or armies they are not performing those deeds of splendor in statesmanship and war over which the pen of the historian usually delights to linger. The people, living, growing, reading, thinking, working, suffering, advancing and dyingthese are all common-place occurrences, neither warming the heart of the observer, nor capable of brightening the page of the chronicler. This, however, is, with the insignificant exception of Liberia, all that is yet to be found in the brief history of the Afro-American race.