Published by South Limestone Books

An imprint of the University Press of Kentucky

Copyright 2020 by The University Press of Kentucky

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are by the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Craig, Berry, author.

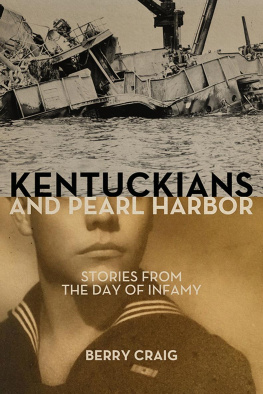

Title: Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor : stories from the day of infamy / Berry Craig.

Description: [Lexington, Kentucky] : South Limestone, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020032976 | ISBN 9781949669275 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781949669282 (pdf) | ISBN 9781949669299 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Pearl Harbor (Hawaii), Attack on, 1941. | World War, 19391945Kentucky.

Classification: LCC D767.92 .C727 2020 | DDC 940.54/266930922769dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032976

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

To my father, the late Motor Machinists Mate First Class BERRY F. CRAIG JR., US NAVY, and my father-in-law, the late Master Sergeant ROBERT P. HOCKER JR., US ARMY, both of whom enlisted after Pearl Harbor and came home with battle stars on their Asiatic and Pacific campaign ribbons.

Introduction

Nearly every American alive at the time can describe how he first heard the news, Walter Lord wrote in the foreword to Day of Infamy, his minute-by-minute account of the Pearl Harbor attack. He marked the moment carefully, carving out a sort of mental souvenir, for instinctively he knew how much his life would be changed by what was happening in Hawaii. No Americans remembered December 7, 1941, with more precision than those who survived the surprise Japanese air raid that plunged the United States into World War II. Caught in the deadly rain of bombs, torpedoes, and strafing fire, they went through successive stages of shock, fear, and anger, Lord added.1

Gunners Mate Second Class James Allard Vessels of Paducah experienced all three emotions aboard the Arizona. The super-dreadnought became the most iconic of the warships sunk on the date President Franklin D. Roosevelt said would live in infamy. Vessels returned to Pearl Harbor for the thirtieth anniversary of the attack. Nineteen years earlier, a memorial had been built over the rusty, bomb-blasted, fire-blackened, and submerged hull of the battleship, which still seeps fuel oil even today. The gleaming white structure straddles but does not touch the Arizona. Inscribed on an inside wall are the names of 1,177 crewmenofficers, sailors, and marineswho perished. Most are still entombed in the ships remains. Reading the roll of the dead, Vessels found a name he was looking for, Gunners Mate Third Class Ross Worth Lightfoot. He was Vesselss partner in a card game they never finished.2

The air-raid alarm sounded around 7:55 A.M., just before morning colors, when the Stars and Stripes was to be ceremonially run up the stern flagstaff. The ships acclaimed band was set to play The Star Spangled Banner. The bands director, Frederick William McKinney, and its drummer, Emmett Isaac Lynch, were Kentuckians. They joined the scramble for battle stations. Under fire, Vessels hurriedly climbed to a machine-gun platform high atop the mainmast; the musicians scurried deep below decks to help pass ammunition up to the gunners. At 8:06, a bomb blew up the Arizona. Vesselss lofty perch saved his life; every member of the band died.3

The Arizona was close to the end of Battleship Row, a procession of capital ships moored next to Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor. The California was first in line. Torpedoes and bombs sank that battlewagon dubbed the Prune Barge for the seemingly endless supply of dried fruit sent from the Golden State. Almost one hundred of its crew died, Fireman First Class Jim Hamlin supposedly among them. From Harlan, Hamlin was, however, alive. He was one of several men from the Bluegrass State whose families received telegrams reporting that their loved ones had been killed or were missing in action. Most of the wires correcting the mistakes arrived before Christmas, thus transforming Yuletide mourning and grief into joy and thankfulness.4

Sundays were usually a day offliberty to sailors and marinesfor most of those in uniform in Hawaii. Joe Sanders, from Mayfield, and a shipmate from the light cruiser St. Louis planned to rent a camera in Honolulu and take pictures in the lush green hills above Hawaiis capital city. Japanese airmen canceled the photo shoot.5

The planners of the Japanese attack knew that success depended on air superiority. So, while most of the planes targeted the Pacific Fleet, others flew off to destroy army, navy, and marine air bases and their planes on the ground. The soldier Calvin Leisure of Ohio County had just finished guard duty at Wheeler Army Airfield, which adjoined Schofield Army Barracks north of Pearl Harbor. He was looking forward to breakfast but never made it through the chow line. Everybody scattered when the enemy airmen pounced, firing cannons and machine guns and dropping bombs on the unsuspecting Americans. Leisure grabbed his M-1 rifle and fought back from a golf course sand trap. John Wood, a marine from Glasgow, managed to finish his morning meal before he spotted strange-looking airplanes flying toward Pearl Harbor. He, too, was at war, though President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not formally declare it so until December 8.6

One of the first antiaircraft projectiles aimed at the Japanese warplanes might have been the sailor J. C. Rileys brand-new baseball bat. A shipmate on the destroyer Case said that he hurled the Louisville Slugger at some low-flying aircraft. From Benton in Marshall County, Riley confessed that he did not remember the toss but did recall losing his bat somehow.7

The army private Herman Horn of Frankfort, the state capital, never knew what became of his breakfastan apple and a bottle of milk. He deposited it in his tent next to his cot, dozed off, and woke up again to the din of airplane engines, explosions, and gunfire. He forsook his sustenance when he and the rest of his outfit were herded into trucks that sped off to shore batteries and antiaircraft guns at Fort Barrette, near Pearl Harbor. They dodged strafing enemy planes on the way. I often wondered where my apple and my milk went, he said.8

Explosions startled the soldier Charles Hocker at Schofield Barracks. He dismissed the noise, figuring planes were dropping harmless smoke bombs in a training exercise. Also an Ohio Countian, he realized his potentially fatal mistake when he saw aircraft painted with round, bright red rising-sun insignia dropping real bombs and shooting real cannon and machine-gun rounds. They killed a lot of my buddies, said Hocker, who suffered a slight leg wound.9

The attack caught the sailor Clarence Meece of Somerset with his trousers down, literally. He was in a headtoilet to landlubberson the light cruiser Raleigh