This book was published with the assistance of the Anniversary Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2020 Jarod Roll

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Set in Miller and Champion by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

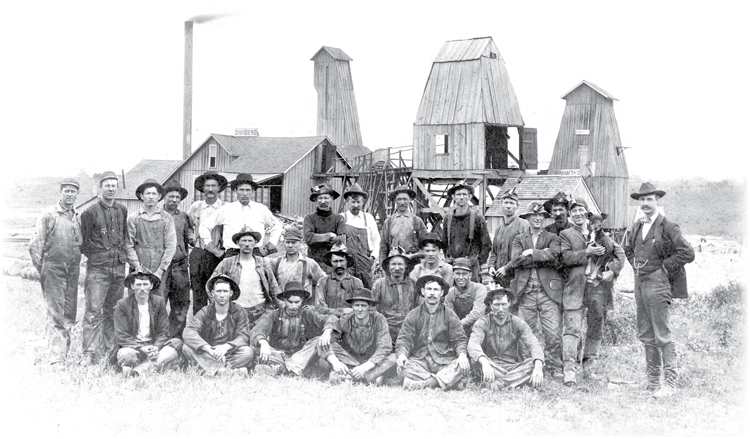

Cover illustrations: black powder image iStockPhoto/Pattadis Walarput; shovelers image courtesy Historical Mining Photographs Collection, Joplin History and Mineral Museum

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Roll, Jarod, author.

Title: Poor mans fortune : white working-class conservatism in American metal mining, 18501950 / Jarod Roll.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052079 | ISBN 9781469656281 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469656298 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469656304 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: MinersTri-State Mining DistrictHistory19th century. | MinersTri-State Mining DistrictHistory20th century. | Working-class whitesAttitudes. | Working-class menAttitudes. | ConservatismTri-State Mining DistrictHistory. | MasculinityEconomic aspects. | White nationalism.

Classification: LCC HD8039.M72 U687 2020 | DDC 305.9/622344097309034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052079

INTRODUCTION

This book is about white working-class American men who opposed social democratic labor unions and politics in the century that culminated in the New Deal. It follows five generations of miners who, beginning in the 1850s, discovered and developed a rich swath of zinc and lead that straddled the boundaries between Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma. By the 1920s, the Tri-State district led the nation in the production of these unheralded but essential metals. From the beginning, the miners pursued class interests that differed, to varying degrees, from those of the men who controlled the land, bought the ore, and smelted the metal. Yet for sixty years, from 1880 to 1940, national labor unions could not organize the Tri-State miners. This outcome mattered. The miners developed a powerful animus against the idea of class-based solidarity, particularly as practiced by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), a pioneer of radical unionism, and later by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Tri-State miners worked, willingly and repeatedly, as strikebreakers against the WFM in a series of clashes across the western United States between 1896 and 1910. Their actions helped to defeat and nearly destroy the WFM. These outcomes also mattered in Tri-State mining communities. Miners resisted government efforts, often backed by unions, to impose health and safety regulations despite the obvious dangers, the worst of which was silicosis, a fatal lung disease. Even during the Great Depression, when the federal government encouraged workers like them to organize for higher pay and greater security, Tri-State miners remained obstinate. The districts majority crushed a promising drive by some of their peers to realize the full benefits of New Deal collective bargaining rights. Rarely, it seemed, had so many American workers fought so long to remain at the raw edge of industrial capitalism.

Tri-State miners baffled, frustrated, and enraged those who tried to get them to change. WFM leaders called them a dangerous class with a deplorable lack of intelligence. Twenty years later, an American Federation of Labor (AFL) organizer blamed the absence of unions in the district on the stupid miner himself. Reformers likewise struggled to make sense of them. A social worker concluded that a feverish unsteadiness warped their social instincts and ideals. Government health and safety investigators, meanwhile, found that the miners seem indifferent, even fatalistic, and will take precautions only if compelled to do so. These commentators concluded, as we might also conclude, that something was wrong with Tri-State miners and that it made them act against their own interests.

The story of the Tri-State miners runs counter to what we know about American labor and working-class history in the decades between the Civil War and World War II. The new labor historians focused on the organizing story of how different kinds of workers banded together in common cause through unions and social movements to improve their working conditions, to articulate, defend, and exercise their rights, and to challenge employers, the state, and capitalism more generally. These stories were often about how workers and activists overcame obstacles and divisions to build solidarity through collective action. Their focus tended to be on the industrial unions that welcomed most workers, generally regardless of skill, race, nativity, or gender, such as the Knights of Labor, United Mine Workers of America (UMW), WFM, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and the wider CIO. The impediments that American workers struggled with, sometimes successfully and sometimes not, were usually seen as coming from external sources, often through elite instruments of power.

Of course, we know that fear and vulnerability hindered the labor movement in this period. We know, too, that many unions were limited by animosities attuned to racial, ethnic, gender, and religious differences that were often manipulated by employers.

Our understanding of American workers has been guided by an assumption that they would join unions and welcome government regulation if only they had the knowledge and freedom to do so. Less conspicuous but nonetheless enduring is a related assumption that working-class democracy would prevail, sooner or later, over divisions of race, ethnicity, and gender. These assumptions rest on a scholarly faith in working-class mutualism. David Montgomery articulated that faith best when he argued that workers in industrial America developed an ideology of mutualism that taught them that their only hope of securing what they wanted in life was through concerted action. Despite differences of race, ethnicity, gender, skill, and politics, he argued, their working-class bondings and struggles informed the shared presumption that individualism was appropriate only for the prosperous and wellborn. Because workers were mutualists, Montgomery concluded, they rejected the ideology of acquisitive individualism, which explained and justified a society regulated by market mechanisms and propelled the accumulation of capital. A whole generation of research and writing on working-class history, he wrote elsewhere, rests on the finding that mutualism, as idea and practice, prevailed in the workplace, community life, and local politics of most working-class Americans. The concept is so powerful that even our understanding of working-class conservatism has been framed, in most cases, by studies of craft unions, such as those in the AFL, the nations largest and most enduring labor organization.