Copyright 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mires, Charlene.

Independence Hall in American memory / Charlene Mires.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 0-8122-3665-3 (acid-free paper)

1. Independence Hall (Philadelphia, Pa.)History. 2. MemorySocial aspectsUnited States. 3. Public historyUnited States. 4. Historic sitesSocial aspectsUnited States. 5. National characteristics, American. 6. Philadelphia (Pa.)Buildings, structures, etc. 7. Philadelphia (Pa.)History. I. Title.

F158.8.I3 M57 2002

974.8'11 21

2002069583

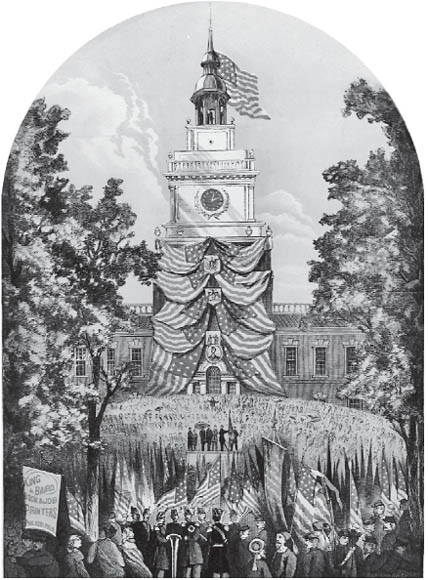

Title page illustration: The Boys in Blue, commemorative

lithograph, 1866 (see )

On fine summer afternoons in Philadelphia, I sit among the bench-warmers of Independence Square. We carry books or newspapers, cold drinks or carry-out lunches, and like the pigeons of the square we roost around one of the most significant historic structures in the United StatesIndependence Hall. In 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence here; in 1787, delegates from the new nation drafted the U.S. Constitution. The United States and the city of Philadelphia have far surpassed their eighteenth-century proportions, but Independence Hall has survived under the protection of historically minded Philadelphians and later the federal government. It is a place both local and national, present and past, alive with activity and frozen in time. Tourists and schoolchildren continually file through the famous building, affirming its importance as the birthplace of the nations founding documents. In its preservation and interpretation at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Independence Hall seems to have passed directly from the eighteenth century to the present. Inside, George Washingtons chair seems to stand just where he left it. The silver inkstand gathers no dust. The clock in the distinctive steeple seems to keep steady time. How remarkable, how inspiring it can be.

Across the United States, hundreds of historic sites and monuments remind and reassure Americans of the presence of the past. We can visit the homes of Jefferson and Washington, the battlefields of Manassas and Gettysburg, and the places that incubated the African American and womens civil rights movements. We can envision Thomas Edison in his workshop or remember Davy Crockett at the Alamo. But most encounters with such places are brief stops on school field trips or summer vacations. Visitors step momentarily into an illusion of the past, consume a carefully carved slice of history, purchase a postcard or two, and move on. Such historical tourism has become an essential contributor to Americans perceptions of their history. More than textbooks, more than history courses, Americans value museums and historic sites as opportunities for experiencing the past.

Because historic places play such a significant role in our sense of a shared national past, they deserve attention beyond the scope of a standard tour or guidebook. Historic places may seem to have obvious stories to tell (what could be more evident than associating Independence Hall with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution?). However, such places have histories beyond the obvious. If the nations historical memory is built upon fragmented, tightly edited stories, we risk losing touch with the greater complexity of national life. We may gain a sense of national unity, but depending on the historic places we choose to visit, we may lose sight of the diversity and conflicts that have characterized the nations history. We may gain a surface understanding of events and a feeling of historic ambiance, but at the expense of full engagement with the deeply rooted issues that define the nations civic life.

In this book, I am getting off the tourist bus and stepping back from one historic placeIndependence Hallto see what can be learned from a broader, deeper history. Although the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution rightfully prevail at Independence Hall, I argue that the significance of the building cannot be fully understood without incorporating the complex cultural and social history that has inhabited and surrounded it for nearly three centuries. This does not require abandoning the traditional associations of Independence Hall, but rather reaching across arbitrary boundaries of time and space. The significance of Independence Hall includes the history of the nations founding, to be sure, but it also extends to the ways Americans have remembered that history at its place of origin. It is a nations history, but it is also a history embedded in one of the nations oldest and largest cities, with a diverse population and a changing urban environment. To see Independence Hall as a place with a long history in an American city does not diminish its significance, I would argue, but rather enhances it. In a more fully articulated history, Independence Hall emerges as a place where successive generations have struggled to define the essence of American national identity.

Buildings, Nations, and Memories

To understand Independence Hall, and potentially other historic places, this book is concerned with three interlocking processes: the construction of a building, a nation, and memory. In this view, nations are defined by beliefs (illusions, some might say) in shared characteristics among citizens. Nations are not fixed entities, defined only by geography; rather, they are continually redefined through processes of reimagining the nation and what it represents.

Where do buildings come in? Certainly they are not the only contributors to national identity, but they have the capacity to facilitate remembering and forgetting.To fully understand the significance of a building, I argue, requires considering the forgetting as well as the remembering. Indeed, aspects of a buildings past that have been obscured by historic preservation may hold the richer story of the construction of national identity. A carefully tended building may belie the conflicts and activity of everyday life that have surrounded it over time.

To think of buildings in terms of the processes of remembering and forgetting is a departure from the usual practice for considering the significance of historic buildings in the United States. Questions about the significance of buildings often arise in the context of decisions about preservation or official historic designation. Should a building be preserved? Does it deserve to be recognized on the National Register of Historic Places? If so, why? The issue of significance is thereby framed as a quest to define what is memorable. This framework, codified in the United States by the Historic Preservation Act of 1966, directs our collective attention toward readily identifiable historic contexts, notable people, events, and architectural distinctiveness. Certainly, associations such as these help to mark a buildings place in history. To stop at this point, however, is to risk overlooking more complex meanings. If memories of famous events and notable people have survived, it is likely that other aspects of the buildings history have been forgotten along the way. The forgotten history, if recovered, may contribute to a richer understanding of the buildings history, potentially revealing changing meanings of the building over time. With this, it is possible to detect how and why successive generations used, changed, restored, or preserved the building in keeping with their regard for its historical associations. This process is a valuable record of interactions between past and present.