Frances Long Reconstruction

IN SEARCH OF THE MODERN REPUBLIC

Herrick Chapman

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2018

Copyright 2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

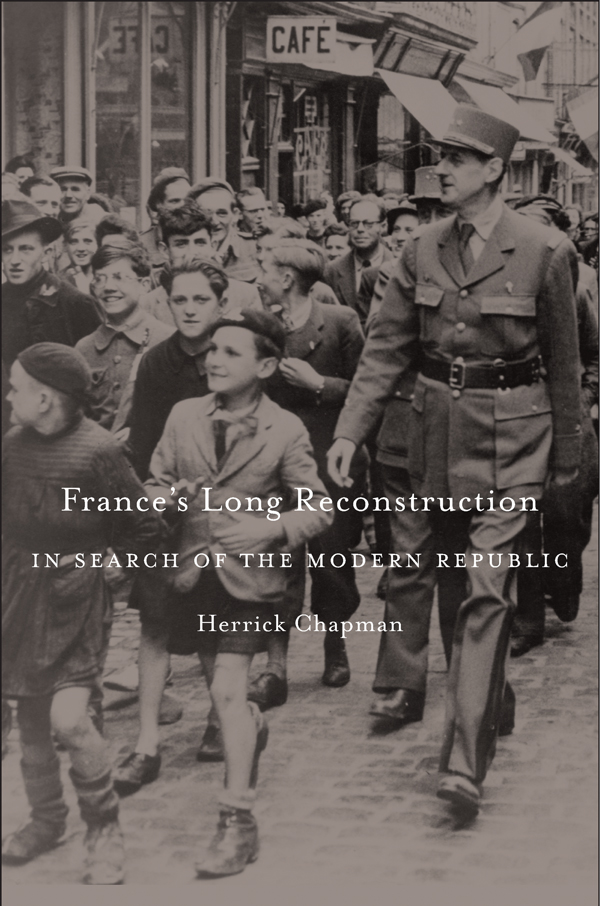

Jacket design: Graciela Galup

Jacket art: Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970) French General and first President of The Fifth Republic. De Gaulle walking through Bayeux, the first French town to be liberated, surrounded by rejoicing populace. On his left is Vienot, representative of the French provisional government in London. World War II: 14 June1944./ Universal History Archive/UIG /Bridgeman Images

978-0-674-97641-2 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-98245-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-98244-4 (MOBI)

978-0-674-98243-7 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Chapman, Herrick, author.

Title: Frances long reconstruction : in search of the modern republic / Herrick Chapman.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015077

Subjects: LCSH: FrancePolitics and government1945 | FranceSocial conditions19451995. | FranceEconomic conditions1945

Classification: LCC DC404 .C464 2018 | DDC 944.082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015077

To Liz, Julia, and Natalie

Contents

- Liberation Authorities: Legitimizing the State from Above and Below

- Available Hands: From Manpower Crisis to Immigration Control

- Shopkeeper Turmoil: Tax Rebels and State Reformers in the Postwar Marketplace

- Family Matters: Expertise, Gender, and Voice in the Social Security State

- Enterprise Politics: The Postwar Nationalizations

- Reformer Dilemmas: Pierre Mends France and Michel Debr as Renovators of the Republic

- Algerian Anvil: War and the Expansion of State Authority

AMGOTAllied Military Government of Occupied TerritoryCADICentre daction et de dfense des immigrsCCOSConseil central des oeuvres socialesCDLComit dpartemental de la LibrationCEContrle conomiqueCFDTConfdration franaise dmocratique du travailCFTCConfdration franaise des travailleurs chrtiensCGCConfdration gnrale des cadresCGCMConfdration gnrale des classes moyennesCGEComit gnral dtudesCGPFConfdration gnrale de la production franaiseCGPMEConfdration gnrale des petites et moyennes entreprisesCGTConfdration gnrale du travailCGTUConfdration gnrale du travail unitaireCNAFConfdration nationale de lartisanat franaisCNEConseil national conomiqueCNPFConseil national du patronat franaisCNRConseil national de la RsistanceCRSCompagnies rpublicaines de scuritDGIDirection gnrale des imptsECSCEuropean Coal and Steel CommunityEDCEuropean Defense CommunityEDFlectricit de FranceEECEuropean Economic CommunityENAcole nationale dadministrationFASFonds daction socialeFFIForces franaises de lintrieurFLNFront de libration nationaleFNOSSFdration nationale des organisations de scurit socialeFOForce ouvrireGDFGaz de FranceHCCPFHaut Comit consultatif de la population et de la familleHECHautes tudes commercialesIGAMEInspecteur gnral de ladministration en mission extraordinaireINEDInstitut national des tudes dmographiquesINSEEInstitut national de la statistique et des tudes conomiquesMNAMouvement national algrienMPFMouvement populaire des famillesMRPMouvement rpublicain populaire (Christian Democratic Party)OASOrganisation arme secrteONIOffice national dimmigrationPCFParti communiste franaisPSUParti socialiste unifiPTTPostes, tlgraphes et tlphonesRATPRgie autonome des transports parisiensSFIOSection franaise de lInternationale ouvrire (Socialist Party)SNCFSocit nationale des chemins de ferSNECMASocit nationale dtudes et de construction des moteurs davionsSTOService du travail obligatoireTVATaxe sur la valeur ajouteUDCAUnion de dfense des commerants et artisansUFCSUnion fminine civique et socialeUFFUnion des femmes franaisesUNAFUnion nationale des associations familialesUNCAFUnion nationale des caisses dallocations familialesUNCMUnion nationale des cadres, techniciens et agents de matrise

PEOPLE LIVING IN FRANCE at the end of World War II faced immense challenges, as did most Europeans who had survived Nazi conquest, genocide, and the ravages of total war. They had to repair the sinews of social solidarity and political community after Nazi occupation, Vichy autocracy, and a virtual civil war in 19431944 between collaborators and the Resistance had torn their country apart. Over two million former French prisoners of war, repatriated labor conscripts, and surviving deportees had to reintegrate into society. Although the death toll in France was half what it had been in World War I, the physical destruction was much larger: a quarter of all buildings were destroyed, compared to just 9 percent in 19141918. Seventy-four of the then ninety dpartements (administrative districts) in metropolitan France were touched by combat, in contrast to thirteen during the first war. A million families were homeless. Just 45 percent of the countrys rail lines were serviceable, and then only in unconnected sections. One locomotive in six was useable.

If people yearned most for a return to normalcy, French leaders across the full sweep of a fractured political landscape believed at the Liberation that reconstruction imposed an even bigger agenda. Many an ordinary citizen was more concerned with getting life back to a stable routine and rebuilding a home or a local school exactly as it had been lidentique, as people put it. Just what this new France should be, however, was hardly self-evident, and as a consequence the question of reconstructionwhat it should be and how to do itremained at the heart of French political combat for more than a decade after the war, and as I will argue, until the end of the Algerian war in 1962.

One thing, though, seemed clear to nearly everyone in 1944, apart from a small market-liberal minority: the French state should serve as pilot and engine for the postwar reconstruction. A heavy reliance on national government would be commonplace across the European continent in the late 1940s; wartime mobilization and public services had already expanded state capacities, and the Allied victory had reconfirmed the legitimacy of state authority. But in France, policy experts in the top levels of the civil service drew on a long history of state centralization to position themselves to play an especially big role in the reconstruction. In the post-Liberation era a wide range of specialistseconomists, demographers, engineers, medical professionals, and a legion of policy experts trained in the lawacquired outsized authority in a nation whose leaders were hell-bent on modernizing their country.

At the same time, the autocratic rule of a collaborationist Vichy regime also left France with a complex political challenge for the reconstructionreviving democracy. The defeat of 1940 had discredited the Third Republic (18701940), making it easier for Vichy and the far Right to cast aside Frances democratic traditions. Without the subsequent failure of the Vichy regime (19401944) to adequately feed, shelter, and protect the nation from Nazi plundering, the renewed thirst for republican democracy might have been longer in coming. But come it did, as the call for democratic renewal soon became ubiquitous in Resistance tracts and crucial for uniting that movements many factions. Leader of the Free French, General Charles de Gaulle, whose democratic credentials U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt doubted, proclaimed as early as 1941 in Londons Albert Hall the desire of the Free French to remain faithful to the democratic principles that our ancestors drew from the genius of our race and that are the very stakes of this life-and-death war. By 1944 nearly every Resistance tract and propaganda message emanating from London, Algiers, Lyon, and Paris in the months leading up to the Liberation called for a democratic revolution.