The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Carmel

With all my love as always

More than ever

And to my parents John and Doreen

Dawn, Gas, Leila and Gaby

Love to the whole tribe

Contents

These are not natural events;

they strengthen from strange to stranger.

The Tempest , Act V, Scene 1

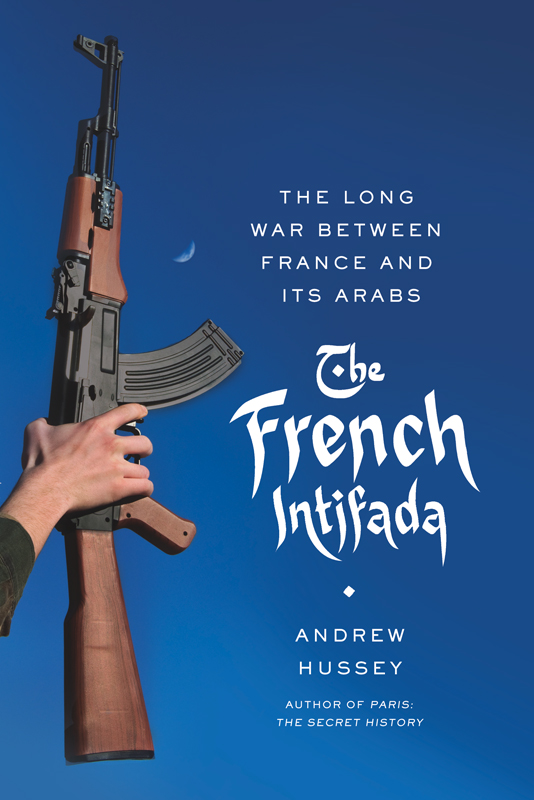

Introduction

Fuck France!

In the late afternoon of 27 March 2007, I was travelling on the Paris metro, heading home after a days work in the east end of the city. I got off at the Gare du Nord to change trains. In a trance lost in the music on my headphones I automatically made for the shopping mall which connects the upper and lower levels of the station. This was where I would normally buy a newspaper and a coffee and then catch a train south to my flat.

But this was no ordinary evening. As I walked up the exit stairs I could smell smoke and hear shouting. The corridors were a tighter squeeze than usual and everyone a little more nervous and bad-tempered than the average rush-hour crowd. As I got nearer the main piazza of the mall, smoke stung my eyes and nostrils, and the shouting grew louder. I could see armed police and dogs. Still, there didnt seem to be too much to worry about. My only real fear was how to get through the tide of commuters, which by now had come to a dead halt, and on to my train home.

I pushed my way through the crowd, burst into the empty piazza, and found myself in dead space, caught in a stand-off between two battle lines on one side police in blue-black riot gear, drumming batons on their clear, hard shields, and on the other a rough assembly of kids and young adults, mainly black or Arab, boys and girls, dressed in hip-hop fashion, singing, laughing, and throwing stuff. You could tell from their accents and manners that these were not Parisians; they were kids from the banlieues the poor suburbs to the north of Paris, connected to the city by the trains running into the Gare du Nord. One African-looking kid was swinging an iron bar and shouting. The bar crashed into a photo booth and a drinks machine. A few yards further on, a fire had been started in a ticket office.

The atmosphere was strangely festive. Behind the reinforced steel and glass of the Eurostar terminal, new arrivals from London were ushered into Paris by soldiers with machine guns the glittering capital of Europe now apparently a war zone. They looked on the scene with horror. But it was exhilarating to watch kids hopping over metro barriers, smoking weed and shouting, walking wherever they wanted, disobeying every single one of the tight rules that normally control access to the station. It was also frightening, because these kids could now hurt you whenever they wanted. They had abolished all the rules, including the rule of law.

There is no word in French or English which expresses the opposite of the verb to civilize: the concept does not exist. But this was anti- civilization in action a transgression of every code of behaviour that holds a society together. Like a terrorist attack or a football riot, the act of anti-civilization is a total experience: it undermines everything all at once. This is not an intellectual concept; it is a feeling. These kids were taking on the whole world around them the police, the train authorities, passers-by wrecking the station, the shops and the offices. And they knew exactly what they were doing.

I stumbled back into the pack of commuters, all transfixed by the spectacle of real, raw violence. No one spoke much. There was nervous laughter but everyone was frightened too. No one could say where this was heading, or where it was going to end.

In fact, the battle went on for another eight hours. I walked most of the way home and then watched the news reports on French television. With the shots of helicopters, flares and paramilitary troopers, these seemed like dispatches from the front line of a distant war rather than an early-evening riot in a commuter railway station only twenty minutes away. And yet the journalists demeanour was mainly calm and unsurprised. This was a level of violence that would have shaken most European governments, but here in France the incident seemed unremarkable, even banal.

Over the next few days, I read the press. Most reporters and eyewitnesses agreed on the chronology. At half past four in the afternoon, a young Congolese man, already known to the police, had been arrested while trying to dodge the ticket barrier. The arrest was heavy-handed and as the cops started hammering the guy, passers-by waded in to support the underdog. Guns were pulled out, batons drawn, and soon enough a riot was in full swing.

But how did this happen? What made the Gare du Nord such a powder keg that the arrest of a ticket dodger could, within minutes, make it the most ungovernable part of French territory? This is where the interpretation of events became confused. In the pages of Le Parisien , the chronicle of daily life in the city, the events were described as une meute populaire (a popular riot). The tone was one of mild approval. Le Parisien is not particularly left-wing, but it is always on the side of the people that most cherished of Parisian myths. This language placed the events at the Gare du Nord in a long tradition of popular uprisings in the city from the days of La Fronde through to the French Revolution and the Commune, these have been a defining feature of Parisian history. Several other newspapers, including the right-wing Le Figaro , reported the same facts with a shiver of horror, adding that the crowds had been chanting A bas ltat, les flics et les patrons (Down with the state, the coppers and the bosses), thereby domesticating the riot as part of the Parisian folklore of rebellion.

But the problem was that none of these accounts was true. The kids I saw didnt give a fuck about the state or the bosses. Most of them didnt have jobs anyway. And although they did hate the police, they would never have used an old-fashioned slang word like flics , which belongs to the Parisian equivalent of the Krays generation. For the rioters, the police were either keufs or s chmitts . The chanting I heard was mostly in French: Nik les schmitts (Fuck the cops), and sometimes in English: Fuck the police! But there was another slogan, chanted in colloquial Arabic, which seemed to hit hardest of all: Naal abouk la France! (Fuck France!). This slogan it is in fact more of a curse has nothing to do with any French tradition of revolt.

* * *

These days France is home to the largest Muslim population in Europe. This includes more than 5 million people from North Africa, the Middle East and the so-called Black Atlantic, the long slice of West Africa which stretches from Mali to Senegal. A short walk around the Barbs district in northern Paris, where almost all of these nationalities are represented in the same tiny, overcrowded space, provides both a vivid snapshot of the diversity of this population and a neat lesson in French colonial history.

The Gare du Nord, at the heart of this district, is frontier territory. It is the dividing line between the wretched conditions of the banlieues, the suburbs outside the city , and the relative affluence of central Paris. It is where young banlieusards come to hang out, meet the opposite sex, shop, smoke, show-off and flirt all the stuff that young people like to do. Paris is both near and distant; it is a few short steps away, but in terms of jobs, housing, making a life, for these young people it is as inaccessible and far away as America. So they cherish this small part of the city that belongs to them.