Published in 2016 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2016 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Amelie von Zumbusch: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The rise of the Jim Crow era/edited by Maria Hussey.First edition.

pages cm.(The African American experience: from slavery to the presidency)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6804-8044-3 (eBook)

1. African AmericansCivil rightsSouthern StatesHistory19th centuryJuvenile literature.

2. African AmericansSegregationSouthern StatesHistory19th centuryJuvenile literature.

3. African AmericansLegal status, laws, etc.Southern StatesHistory. 4. Southern StatesRace relationsJuvenile literature. 5. RacismSouthern StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. 6. African AmericansHistory18631877Juvenile literature. 7. African AmericansHistory18771964Juvenile literature. I. Hussey, Maria.

E185.92.R58 2015

323.1196073075dc23

2014039059

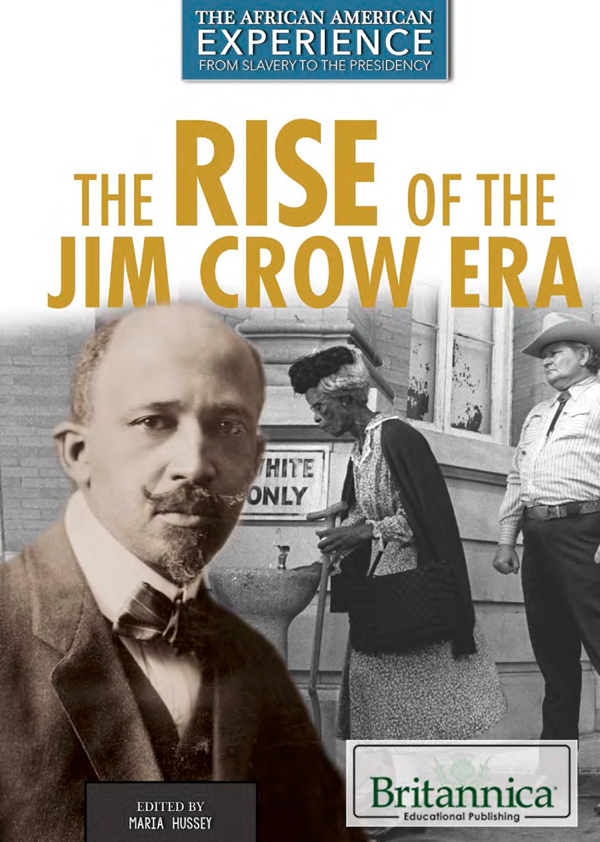

Photo credits: Cover (W.E.B. Dubois), pp. 5, 9, 13, 17, 26, 29, 30, 33, 38, 44, 46, 49 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; cover (background) CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images; p. 11 Collection of the New-York Historical Society, USA/Bridgeman Images; p. 14 Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, France/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images; p. 19 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; pp. 2021 Newagen Archive/The Image Works; p. 24 Jose Gil/Shutterstock.com; p. 34 Johnston (Frances Benjamin) Collection/Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (LC-J601-302); p. 35 National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Department of Agriculture, CC BY 2.0; p. 41 Apic/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 42 TopFoto/The Image Works; p. 50 John Deakin/Picture Post/Getty Images; pp. 52 Joe Amon/The Denver Post/Getty Images; p. 54 R. Gates/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 56 Schomburg Center, NYPL/Art Resource, NY; p. 60 J. T. Vintage/Bridgeman Images; pp. 6263 Afro Newspaper/Gado/Archive Photos/Getty Images; interior pages background texture iStockphoto.com/Piotr Krzelak.

CONTENTS

J im Crow laws were designed to create two separate societies in the Southone white, the other black. Separate areas in which to live, separate railroad cars, drinking fountains, hospitals, restaurants, schools, even separate cemeteriesseparate but equal in theory but certainly not in practice.

These laws existed to enforce racial segregation in the South from about 1877, which marked the end of the formal Reconstruction period, to the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s. Jim Crow was the name of a minstrel routine (actually Jump Jim Crow) performed beginning in 1828 by its author, Thomas Dartmouth Rice, and by many imitators. The term came to be a derogatory epithet for blacks and a designation for their segregated life.

From the late 1870s, Southern state legislatures passed laws requiring the separation of whites from persons of color in public transportation and schools. Anyone known or strongly suspected to be of some degree of black ancestry was for this purpose a person of color. The preCivil War distinction favoring those whose ancestry was known to be mixedparticularly the half-French free persons of color in Louisianawas abandoned. The segregation principle was extended to parks, cemeteries, theaters, and restaurants in an effort to prevent any contact between blacks and whites as equals. It was codified on local and state levels and most famously with the separate but equal decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

This sign from a bus station in Rome, Georgia, points to the location of the stations colored, or African American, waiting room.

During this period, a number of leaders emerged to fight for the African Americans oppressed by these unfair laws. Booker T. Washington, the dominant African American leader at the turn of the 20th century, called on blacks to cease agitating for political and social rights and to concentrate instead on working to improve their economic conditions. Meanwhile, black leaders opposed to Washington began to emerge. The historian and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois criticized Washingtons accommodationist philosophy in The Souls of Black Folk (1903). Others were William Monroe Trotter, the militant editor of the Boston Guardian, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a journalist and a crusader against lynching. They insisted that blacks should demand their full civil rights and that a liberal education was necessary for the development of black leadership. At a meeting in Niagara Falls, Ontario, in 1905, Du Bois and other black leaders who shared his views founded the Niagara Movement. Members of the Niagara group joined with concerned liberal and radical whites to organize the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP; initially known as the National Negro Committee) in 1909. The NAACP journal The Crisis, edited by Du Bois, became an effective organ of propaganda for black rights. The NAACP won its first major legal case in 1915, when the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the grandfather clause, a constitutional device used in the South to disenfranchise blacks.

T he years immediately following the Civil War brought both challenges and new opportunities for African Americans. Many newly freed slaves had trouble finding work and struggled to feed, clothe, and house themselves and their families. Given a free hand in managing their own affairs, the Southern states enacted a number of laws intended to assure that white supremacy would continue. These laws are known as the black codes. In many ways they resembled the slave codes that had existed before emancipation. The black codes intended to secure a steady supply of cheap labor and continued to assume the inferiority of the freed slaves. These laws permitted blacks to legally marry other blacks but did not allow them to vote or to serve on juries. Blacks could testify in court only in cases involving members of their own race. Provisions of the codes compelled blacks to work, no matter what the terms or the conditions under which they worked. The areas in which the freed slaves could purchase or rent property were specified. Punishments were imposed on blacks who owned firearms, who were absent from work, or who were insulting to white people.

RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION

However, the Radical Republicans, a group in the U.S. Congress, were upset that the people who had controlled the Confederacy were still in power in the South. They called for new governments to be set up. They expanded the Freedmens Bureau, which provided food and medical care for former slaves, as well as set up schools for them. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens, who were to enjoy equality before the law. White Southerners who had participated in the rebellion were disenfranchised (barred from voting). Blacks, white Southerners who had not joined the rebellion, and white Northerners who moved to the South were allowed to vote and assumed political leadership in the Southern states.