The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To Annie

Pour le bel aujourdhui

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Pat Sullivan for reading and critiquing the manuscript; my editor, Diane Reverand, for her support and belief in the project; my agents, Barbara Lowenstein and Madeleine Morel; my colleagues Bill Jersey and Sam Pollard; Ed Breslin for his editing skills; and WNET/Thirteen for helping make the series possible. I am also grateful to all the scholars without whose help the film series upon which this book is based would not have been possible. And especially those men and women I was privileged to interview and who shared with me their stories of tragedy and triumph in the age of Jim Crow.

INTRODUCTION

First on de heel tap, den on the toe

Every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow

Wheel about, and turn about en do js so.

And every time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.

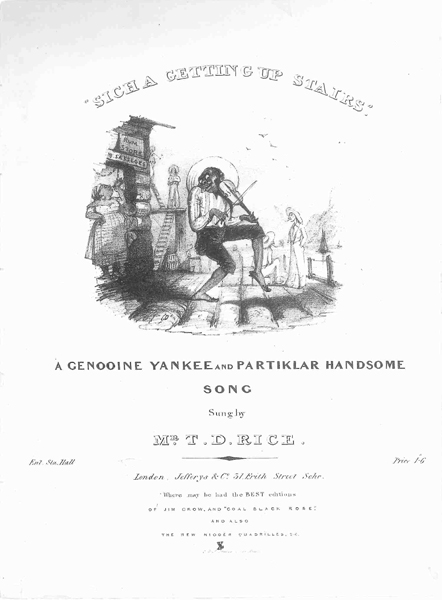

In 1828, Jim Crow was born. He began his strange career as a minstrel caricature of a black man created by a white man, Thomas Daddy Rice, to amuse white audiences. By the 1880s, Jim Crow had become synonymous with a complex system of racial laws and customs in the South that ensured white social, legal, and political domination of blacks. Blacks were segregated, deprived of their right to vote, and subjected to verbal abuse, discrimination, and violence without redress in the courts or support by the white community.

It was in the North that the first Jim Crow laws were passed. Blacks in the North were prohibited from voting in all but five New England states. Schools and public accommodations were segregated. Illinois and Oregon barred blacks from entering the state. Blacks in every Northern city were restricted to ghettoes in the most unsanitary and run-down areas and forced to take menial jobs that white men rejected. White supremacy was as much a part of the Democratic Party in the North as it was in the South.

Northern racial barriers slowly fell after the Civil War. In 1863, California permitted blacks to testify in criminal cases for the first time. Illinois repealed its laws barring blacks from entering, serving on juries, or testifying in court. New York City, San Francisco, Cleveland, and Cincinnati all desegregated their streetcars during the war. Philadelphia followed two years after the war ended. As Northern states repealed some of the more discriminatory legislation against Jim Crow, socially, if not legally, Jim Crow remained in effect. With a few exceptions, blacks for the most part were not allowed to eat in the same restaurants, sleep in the same hotels, or swim at the same beaches as whites. Schools were usually segregated, as were many public events. Most Northern whites shared with Southern whites the belief in the innate superiority of the white race over the black.

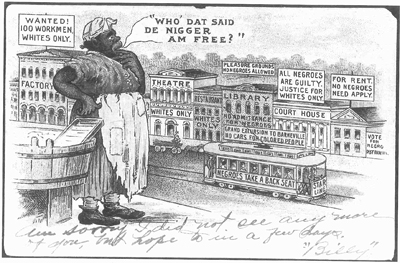

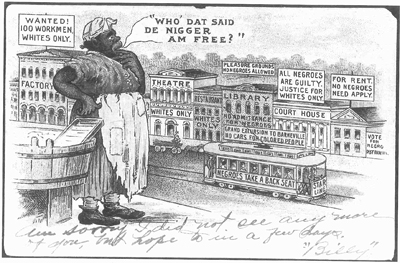

As punitive and prejudicial as Jim Crow laws were in the North, they never reached the intensity of oppression and degree of violence and sadism that they did in the South. A black person could not swim in the same pool, sit in the same public park, bowl, play pool or, in some states, checkers, drink from the same water fountain or use the same bathroom, marry, be treated in the same hospital, use the same schoolbooks, play baseball with, ride in the same taxicab, sit in the same section of a bus or train, be admitted to any private or public institution, teach in the same school, read in the same library, attend the same theater, or sit in the same area with a white person. Blacks had to address white people as Mr., Mrs., or Mizz, Boss, or Captain while they, in turn, were called by their first name, or by terms used to indicate social inferiorityboy, aunty, or uncle. Black people, if allowed in a store patronized by whites, had to wait until all white customers were served first. If they attended a movie, they had to sit in the balcony; if they went to a circus, they had to buy tickets at a separate window and sit in a separate section. They had to give way to whites on a sidewalk, remove their hats as a sign of respect when encountering whites, and enter a white persons house by the back door. Whites, on the other hand, could enter a black persons house without knocking, sit without being asked, keep their hats on, and address people in a disrespectful manner. Whites and blacks never ate together, never went to school together, shook hands, or played sports together (except as children). And while the degree of these restrictions often varied from state to state and county to county, white supremacy was the law of the South, and the slightest transgression could be punished by death.

White violence and oppression, however, were only one part of the story of the era of Jim Crow. The other dimension was the ongoing struggle of African Americans for freedom. This struggle took many forms: direct confrontation, subversion, revolt, institution building, and accommodation. This story was a missing piece of history as far as most Americans were concerned, motivating this book and the film series on which it was based.

This racist postcard, intended to show blacks in a comic stereotypical manner, actually reveals the extent to which segregation had spread over the South by the early twentieth century.

* * *

The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow was born out of a four-hour television series with the same name for PBS on the African-American struggle for freedom during the era of Jim Crow. We chose to focus on the South, even though racism was endemic in the North, because it was in the South that racism and white supremacy manifested their most virulent form. The South institutionalized segregation and disfranchisement by law, custom, and violence. From the late 1880s until 1930, it was rare for a white person to speak out publicly against segregation and white supremacy, especially in the South. The Souths obsession with racial subordination reinforced the same tendencies that existed throughout the nation. By the end of the nineteenth century, white supremacy, once considered a Southern peculiarity, had become a national ideology.

The series took us seven years to plan, research, write, shoot, and edit, two years longer than it took Ken Burns to make his ten-hour documentary on the Civil War. Without our team of some twenty scholars who guided and corrected us along the way, the films would never have been made. One of the difficulties we encountered was finding images and documents to tell our story in the period between 1880 and World War I. There is not an abundance of material on African-American life in this period because Southern whites, who controlled the image-making process, had little interest in documenting or preserving records of black life prior to the 1930s. The most notable exception to this was lynching. White photographers often capitalized on the atrocity by selling images for postcards or souvenirs of the event.