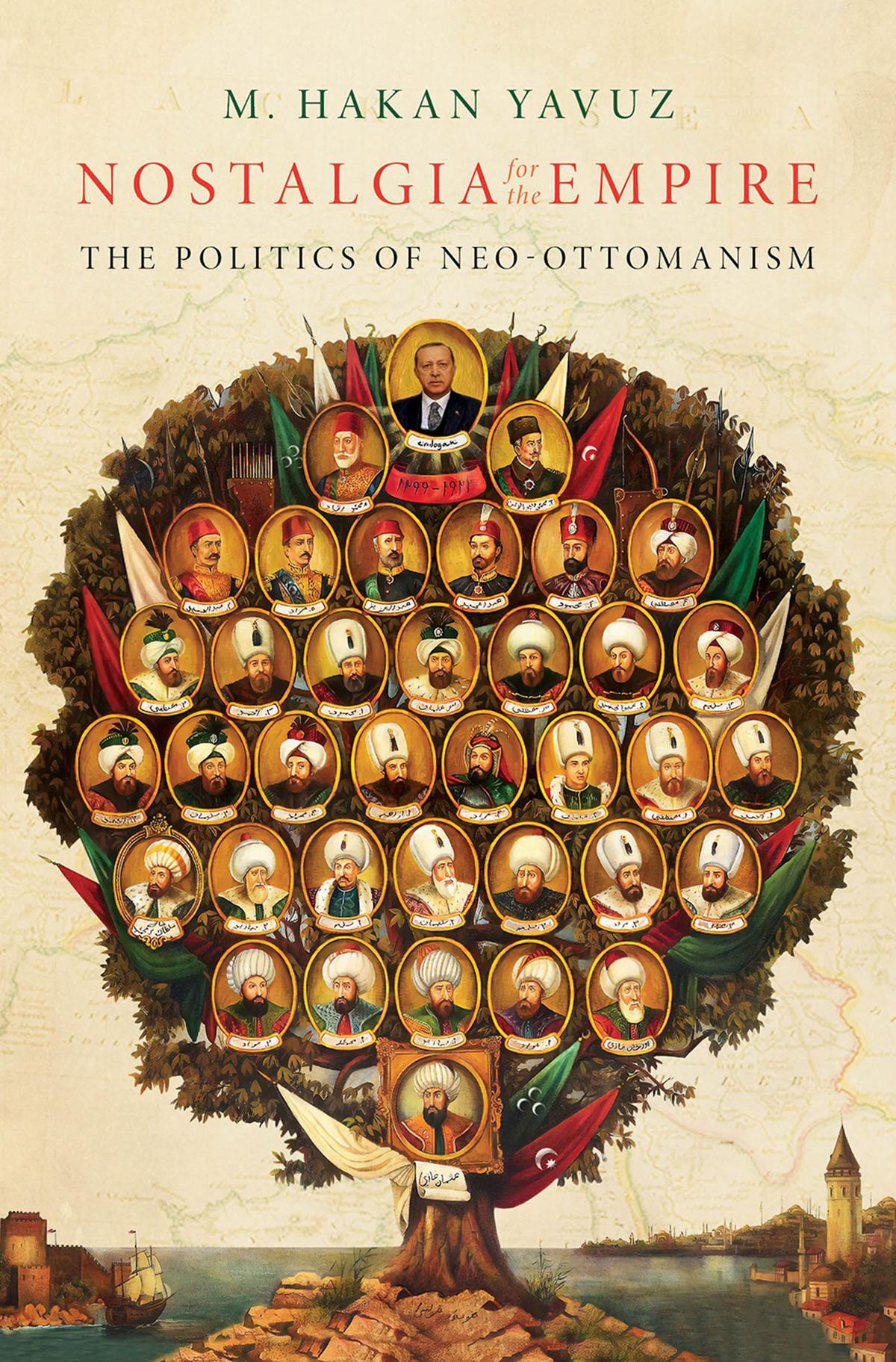

Nostalgia for the Empire

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yavuz, M. Hakan, author.

Title: Nostalgia for the empire : the politics of neo-Ottomanism / M. Hakan Yavuz.

Other titles: Politics of neo-Ottomanism

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019051762 (print) | LCCN 2019051763 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780197512289 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197512302 (epub) |

ISBN 9780197512296 (updf) | ISBN 9780197512319 (online)

Subjects: LCSH: TurkeyHistoryOttoman Empire, 12881918Historiography. |

Turkish literatureHistory and criticism. | Collective memoryTurkey. |

NostalgiaTurkey. | Group identityTurkey.

Classification: LCC DR438.8 .Y38 2020 (print) | LCC DR438.8 (ebook) | DDC 956.1/015dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051762

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051763

This book is dedicated to

Armand and Kaan Yavuz

Contents

Map 1 Map of the Ottoman Empire

Map 2 Map of Modern Turkey

One of my most vivid memories from childhood in Bayburt is ren or ruined buildings. There were many such ren in the village and in the city center of Bayburt. When I moved to Istanbul and later Ankara, these powerful childhood memories stayed with me. I saw the issue of identity in Turkish society as ren, ghostly remnants that seek to rehabilitate themselves with the Seljuk and Ottoman Islamic past. Nostalgia permeated this provincial town, which had never fully accepted the Westernizing reforms of the Republic. It is not surprising that Bayburt ranked first in supporting Erdoans presidential bid and has remained a bastion of conservative Islamic politics.

In Bayburt, nostalgia is an emotion steeped in history with political implications. The nostalgic feeling in Bayburt stemmed not from the failure of Kemalist (those who espouse Mustafa Kemals ideas of nationalism and secularism) modernity, as some scholars have argued, but rather it has inspired endeavors for forging a new dynamic future. For the residents of Bayburt, looking back to the Ottoman model provides an objective on which to build a major state and to accomplish that objective on the foundations of the Turkish Republic. Primarily, the current economic and political elite, centered in the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalknma Partisi, or AKP), is nostalgic for the Ottoman Empire and seeks to enhance the state more than society, arguing that strengthening economic and social circumstances will be necessary to empower the state. The proposition of no state, no Islam means that faith and nation cannot survive without a powerful state, and this idea still dominates much public thinking in Anatolia. Thus, there is an overlap in the goals expressed by the Young Ottomans, the Young Turks, and the founding fathers of the Turkish Republic, for enhancing the power of the state.

The people of Bayburt are nationalistic, religious, and state-centric. Yet God in Bayburt competes with devotion to the state. This state-centric culture is a by-product of the three major traumatic occupations of the town by Russia in 1828, 1878, and 1915 and the bloody local conflict with Armenian militias. The memory of the last war (i.e., World War I) and the Russian-backed Armenian control of the city is highlighted more than any other event. Moreover, the majority of the people of Bayburt are descendants of muhacirs, ethnically cleansed by Tsarist Russia from the Caucasus. Today, Svetlana Boyms observation of nostalgia as being homesick and sick of home at the same time In Bayburt, the shadow of the Ottoman past is part of daily exchanges about politics, economy, and social issues, as if the Ottoman past has always been the context for the conversation. Especially among the conservative segments of the population, there is a rosy image of the past as perfect and harmonious, far different from present circumstances. People talk about the Ottoman period as a golden age, even if they have a limited scholarly reading of its history. I have always wondered why the past, especially the Ottoman era, has dominated daily politics in Turkey. This constructed form of Ottomanism, known as neo-Ottomanism, is the manifestation of Turkeys strong interest in its own history, but it is also a testament to the still bitterly contested issue of national identity. With the current wave of nostalgia, the Turks seek to ameliorate present difficulties with memories of a glorious heritage both real and imagined.

Neo-Ottomanism is an emotional, nostalgic identity. Although obtaining an accurate definition upon which everyone could agree is difficult, there is a generic and working definition that means rooting present notions of Turkish national identity within their Ottoman Islamic heritage. It also entails deeper and renewed cultural and economic engagement with territories and societies once ruled by the Ottoman state and an attendant desire to renew leadership of the Muslim world to fend off ongoing destructive Western and Russian invasions and imperialism in the region. It is based on a strong sense of historical consciousness about the Ottoman past. Neo-Ottomanism, as a form of identity and an ideology in the hands of cultural and political circles of elites and the conservative masses, is rooted in historical sentiment and is undeniably linked to emotion. Islamic and Ottoman history have been fused and intertwined through memory. Finally, neo-Ottomanism links identity to national dignity, as it offers a code of moral language for self-determination and autonomy. For some Turks, Ottomanism is not about the restoration of the past but prophetic in nature. Interestingly, some intellectuals believe that through the discourse of neo-Ottomanism, Turkey could be transformed from a monolithic top-down nation-state to an entity defined by a more tolerant and pluralistic multiethnic and multicultural polity. For example, when I asked a politician to expand upon what he meant, he said,