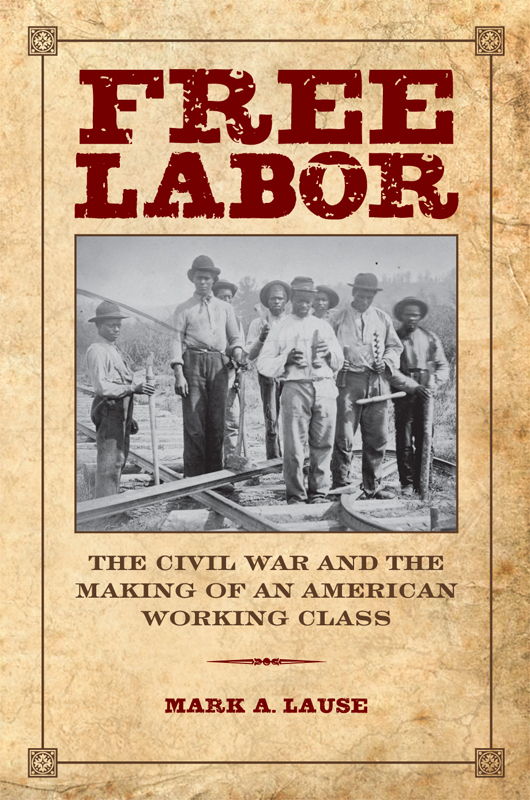

FREE LABOR

THE WORKING CLASS

IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Editorial Advisors

James R. Barrett, Julie Greene, William P. Jones,

Alice Kessler-Harris, and Nelson Lichtenstein

FREE LABOR

The Civil War and the Making

of an American Working Class

MARK A. LAUSE

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2015 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lause, Mark A.

Free labor : the Civil War and the making of an

American working class / Mark A. Lause.

pages cm.(The working class in American history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03933-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-08086-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09738-6 (e-book)

1. Working classUnited StatesHistory19th

century. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861

1865Social aspects. 3. Working classUnited States

Social conditions19th century. 4. Labor movement

United StatesHistory19th century. 5. United

StatesSocial conditions19th century. I. Title.

HD 8070.L39 2015

305.5'62097309034dc23 2015008312

Contents

Acknowledgments

Work on this subject has gone on for decades, as I gathered up what has become the bits and pieces of this study from almost every library or archive Ive ever visited. These included the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the American Antiquarian Society, and the state historical societies and archives of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. The staff of these instituions have never failed to impress me with their expertise. The staff of the Langsam Library at the University of Cincinnati, particularly Milkaila Corday, who has managed the interlibrary loan services there for almost as long as I have been here, has always provided essential support with similar expertise.

That said, this kind of sweeping research project could not have been possible without the massive technological changes in recent years. The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System Web site of the U.S. National Park Service and the even more informative American Civil War Research Database have precluded what would have been innumerably repeated research trips to the military records in Washington, D.C. I ruthlessly exploited the availability of digital sources from Google Books and the Internet Archives to the burgeoning newspaper-digitalization projects, notably Chronicling America from the Library of Congress and state newspaper digitalization projects, as well as the ProQuest subscriptions available by subscription to libraries. It should be added that many of these for the period had already been culled, transcribed, and indexed by Vicki Bettss powerful little site on Civil War Newspapers at the University of Texas at Tyler.

I frankly confess that I tend to be a much more solitary worker in researching these projects than I should be. Nevertheless, bringing such a long project to fruition has benefited tremendously from periodic short exchanges with too many people in the field to name without serious risk of missing someone. However, I would be remiss without noting my appreciation of the encouragement for this project by Bruce Laurie, Bruce Levine, and Nikki Taylor, as well as Laurie Matheson, the editorial staff, and the manuscript readers at the University of Illinois Press who forced the reshaping of part of this manuscript. As they have for years, my colleagues Janine Hartman at the University of Cincinnati and L. J. Andrew Villalon at the University of Texas have provided a sounding board, the former also adding a needed second pair of eyes to the more troublesome parts of the manuscript. All contributed to whatever the manuscript can achieve, while the mistakes and errors are my own.

Introduction

The Civil War proved central to the making of an American working class. Yet the intersection of labor history and the conflict itself with regard to the future nature of labor in the country has stirred remarkably little interest among historians in either field. Historians have certainly written about a struggle that subsumed large sections of the workforce and transformed the working-class experience forever. Yet the role of workers in shaping the course of that conflict and the role of the conflict itself in shaping the future nature of labor and the labor movement has stirred remarkably little interest in the field as a whole. Interest in the demise of slavery has turned largely on the evolution of government policies. Too, free laboring people, as such, usually find a place in the wars history only in the brief cameo in the New York City draft riots, and the admirable interest in slavery still often turns on the evolution of institutional policies rather than slaves as active agents in the making of their own history. Workers themselves understood this. Indeed, an Iowa harnessmaker once described the war as a great labor movement. Conversely, historians of labor, with a few exceptions, usually do no more than mention the subject in passing, focusing instead on the later institutional development of unions or the social conditions that cultivated the postwar movement.

The U.S. census provides a crude measure of the workforce. For these years associated with the war, it offered gendered counts by age groups without enumerating skilled and semiskilled adult workingmen or even distinguishing between master craftsmen and hired men, but the numbers do provide some grounds for

* * *

Our concern is the role of the Civil War experience in the making of an American working class in the sense that E. P. Thompson envisioned that process in England. Thompson resurrected the insights of Karl Marx, understanding class as a process of self-definition through which workers come to see themselves as playing a distinct role in society. Workers express this shared sense of themselves through their organization of demonstrations, picket lines, unions, parties, and other material activities. Conversely, class has little material meaning for participants in a workforce who do not see themselves as having a distinct set of concerns. Finally, seeing this as a process understands the making as an issue of degrees.

The war wrought major changes on this working population. Most obviously, it ended slavery and radically expanded the numbers of hired laborers. War-related industrialization expanded the manufacturing base, and the massive exodus of enslaved workers into the wage-earning population roughly doubled this greater size. More subtly, the military experience imposed a qualitatively new discipline and regulation that made for a more easily managed labor.

Getting at how these workers actually saw themselves takes real effort. They expressed this partly through associations where workers chose to unite with each other as workers to formulate and foster common concerns, but these organizations marked the documentary record only when they reached a certain size or engaged in mass meetings, demonstrations, or strikes. Certainly, a cross-section of workers in America had begun to behave and to explain themselves in much the same way as Thompsons English workers had, suggesting that they saw themselves and their relationship to society in distinct ways, but the manifestation of this was not always the same. That is, the organizations and rhetoric that served their peers in Britain and Europe appeared in a system with an endemic labor shortage, growing amid massive resources with an insufficient workforce to exploit those riches. The masters and rulers of American society resolved this problem, in part, by expanding the enslaved population of African Americans. For their part, these owned workers came to understand themselves and their social realities in class terms that proved quite distinct from that of the organized white-labor movement.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.