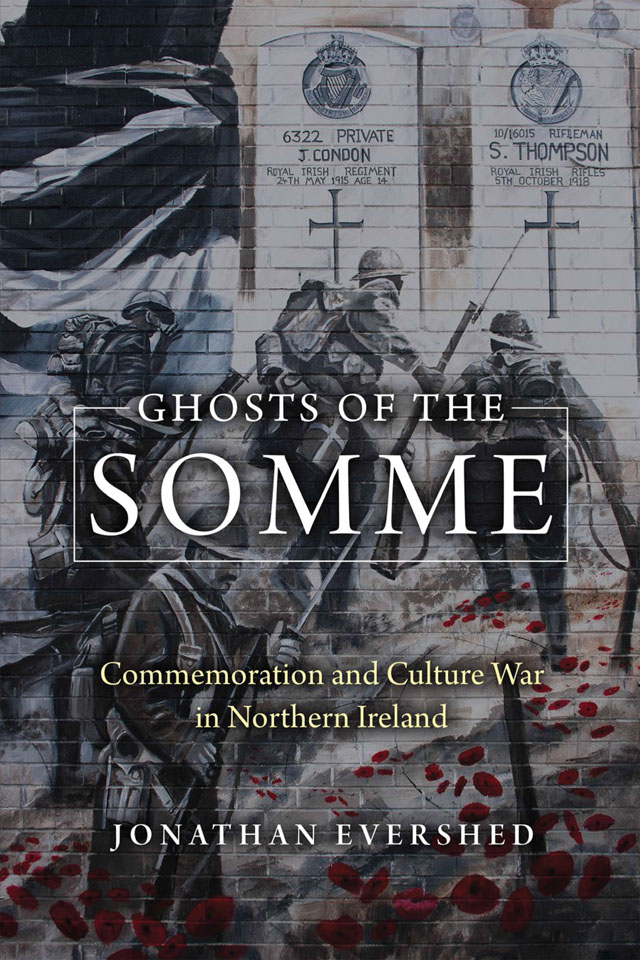

GHOSTS OF THE SOMME

GHOSTS OF THE SOMME

Commemoration and Culture War

in Northern Ireland

JONATHAN EVERSHED

UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME PRESS

NOTRE DAME, INDIANA

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

undpress.nd.edu

All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2018 by University of Notre Dame

Published in the United States of America

Title page image: The Road to the Somme Ends,

https://extramuralactivity.com/2013/01/11/the-road-to-the-somme-ends/.

Image courtesy of Extramural Activity.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Evershed, Jonathan, 1989 author.

Title: Ghosts of the Somme : commemoration and culture war in

Northern Ireland / Jonathan Evershed.

Other titles: Commemoration and culture war in Northern Ireland

Description: Notre Dame, Indiana : University of Notre Dame Press, [2018] |

Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011948 (print) | LCCN 2018012581 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780268103873 (pdf) | ISBN 9780268103880 (epub) |

ISBN 9780268103859 (hardcover : alk. paper) |

ISBN 0268103852 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Somme, 1st Battle of the, France, 1916Centennial

celebrations, etc. | World War, 19141918Northern IrelandAnniversaries,

etc. | Great Britain. Army. Division, 36th. | World War, 19141918

Ireland Influence. | Collective memoryNorthern Ireland. |

Group identityNorthern Ireland. | Political cultureNorthern Ireland. |

IrelandPolitics and government21st century.

Classification: LCC DA962 (ebook) | LCC DA962.E84 2018 (print) |

DDC 940.4/272dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011948

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

For Ray Silkstone

Who taught me about arguments:

how to make them and how to hear them

The future to come can announce itself only as such and in its purity only on the basis of a past end. The future can only be for ghosts. And the past.

J. Derrida, Spectres of Marx

CONTENTS

Dominic Bryan

FOREWORD

The use of the poppy as a symbol of commemoration can be dated to the years following the First World War. In Australia and New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Canada, the practice of wearing the poppy and laying wreaths at cenotaphs serves as an annual reminder of those who have given the ultimate sacrifice. The political power of the poppy places it at the center of the nations story, a story that is physically structured in cenotaphs and memorials at the center of city, town, and village and is worn close to the heart by citizens every November in an apparently simple and universally agreed on statement of remembrance.

A closer examination of the narratives surrounding the avowedly simple poppy, however, reveals a distinct lack of agreement, great inconsistency, and, often, contention. In each country in which the poppy is worn the narratives about it differ significantly, as the particularities of each nations relationship with war and sacrifice demand more nuanced readings of its symbolism. Very often it is a particular battle around which the national narrative is structured. In Australia, it is the stark story of the Battle of Gallipoli that provides the focal point. The narrative encompasses a scathing critique of Britains incompetent and clumsy handling of the invasion of Turkey in 1915, while it simultaneously asserts Australias rightful place among the nations and profiles a white, masculine (and increasingly contested) ideal-type for the Australian citizen.

In the United Kingdom, the design and prevalence of the poppy has become considerably more pronounced in the twenty-first century. The simple flower has become larger, more embellished, and even jewelencrusted. Prominent British sports teams now have their array of international players wear an embossed poppy on their shirts during the month of November, and the few who refuse to do so are widely and roundly condemned. The international football teams of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland have demanded the right to wear the poppy at international matches, defying the rules of FIFA, the football worlds governing body, about the display of political symbols. Commemoration has become both more enforced and more controversial.

The complex and conflicted symbolism of the poppy is nowhere better illustrated than in Ireland. The same years that saw it first worn as a symbol of remembrance also saw Ireland divided into two states. Northern Ireland became a devolved region of the United Kingdom, while the other twenty-six counties took dominion status before eventually becoming the Republic of Ireland. The First World War did not provide a suitable narrative, nor the poppy a suitable symbol, for the southern state, where the 1916 Easter Rising delivered the story of sacrifice around which national identity was structured. But in Northern Ireland, a story of sacrifice for Ulster and for the empire sustained relationships with the British mainland. Like the Australian soldiers at Gallipoli, the soldiers of the 36th (Ulster) Division at the Battle of the Somme came to symbolize a gallant and foundational sacrifice for King and country.

This sophisticated and detailed book by Jon Evershed offers us real insight into the contemporary politics and poetics of commemoration. In particular, it examines the narratives and practices of commemoration by groups of working-class Unionists in Northern Ireland. It explores how and why, in Belfast, the poppy has migrated from its traditional habitat on lapels and at the foot of memorials in the early weeks of November to appear year-round in Loyalist paramilitary murals and on the uniforms and instruments of marching bands during the parades of the summer months. It helps to explain why it is not uncommon to see people in Northern Ireland wearing a poppy at any point throughout the year, or even to see etched in peoples skin as part of a tattoo. In Northern Ireland, the sacrifice of which the poppy is symbolic belongs to complex narratives and divisive claims about British sovereignty, citizenship, and identity on the island of Ireland.

And yet, as Jon Evershed maps, the 1998 multiparty Agreement has helped to create a new environment in which the poppy and its story have increasingly been salvaged and reclaimed in the Republic of Ireland and, consequently, in which a narrative of common sacrifice by Protestant and Catholic, British and Irish, on the fields of France and Flanders has been constructed and rehearsed. This narrative has been encouraged by both the British and Irish states in the name of peace-building, to the point that it appears to threaten the particularity of the loyaltyand the identityof some of the Unionists of Ulster.

Conflicting narratives, driven by the politics of group identity, are plotted throughout this book. Importantly, it captures a moment in time, a decade of centenaries, by and through which these politics are currently framed and negotiated. As a work of anthropology, people and their practices are central to the analysis. What people say and what people do when they commemorate are captured through Eversheds ethnography, and he provides a challenging commentary on the social, cultural, and political role of remembrance. This volume is therefore an important case study of commemorative practice, of the will to commemorate, and of the politics of remembering.