Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

About NYU Press

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

Liberty Tree

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2006 by New York University

All rights reserved

Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data

Young, Alfred Fabian, 1925

Liberty tree: ordinary people and the American

Revolution / Alfred F. Young.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN13: 9780814796856 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN10: 0814796850 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN13: 9780814796863 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN10: 0814796869 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Social

aspects. 2. RadicalismUnited StatesHistory18th

century. I. Title.

E.209.Y68 2006

973.3dc22 2006008340

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper,

and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

Why Write the History of Ordinary People?

Joseph Plumb Martin was a Connecticut farm boy who enlisted in the Continental Army in 1777 when he was sixteen and served until 1783, the length of the Revolutionary war. He was a private, then a sergeant, in the Corps of Miners and Sappers who conducted sieges of enemy fortifications, a dangerous service. In 1830, when he was seventy, Martin published his memoir, A Narrative of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier, which has to be the best autobiography that has survived for a rank-and-file soldier: pungent, humorous, and always irreverent.

After describing a particularly hard-fought battle he had taken part in, Martin wrote, but there has been little notice taken of it, the reason for which is, there was no Washington, Putnam, or Wayne there. Had there been the affair would have been extolled to the skies. He was naming three of the most famous generals of the war: Israel Putnam, Anthony Wayne, and, of course, the commander in chief George Washington, under whom he had served from Valley Forge to Yorktown. Great men get great praise; little men, nothing, wrote Martin. He conceded that every private soldier in the army thinks his service is essential to carry on the war he is engaged in, but he asked, What could officers do without such men? Nothing at all. Alexander never could have conquered the world without private soldiers.

Martin remembered the army in the terrible winter of 1777, when soldiers were not only starved but naked. The greatest part were not only shirtless and barefoot but destitute of all other clothing, especially blankets. And he remembered joining his fellow soldiers, exasperated beyond endurance, by such conditions, who resorted to mutiny in 1780. To Martin his comrades in arms were a family of brothers, but a half century after the war he was bitter. When soldiers enlisted, he wrote, they were promised a hundred acres of land.... When the country had drained the last drop of blood it could screw out of the poor soldiers, they were turned adrift like old worn-out horses, and nothing said about land to pasture them upon.... Such things ought not to be.

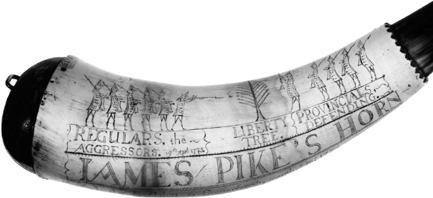

The liberty tree is at the center of a scene carved on James Pikes powderhorn. To the left are British soldiers labeled REGULARS the AGGRESSORS, April 19, 1775, and to the right, PROVINCIALS DEFENDING. The scene represents the patriot version not only of the Battle of Lexington but of the Revolutionary war. Pike was a Massachusetts militia man who served at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Soldiers stored their gunpowder in powderhorns. Photograph courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

After the war, Martin, the landless veteran, squatted on land on the Maine frontier confiscated from Loyalists and bought by General Henry Knox, one of the Great Proprietors who acquired legal title to hundreds of thousands of acres for a pittance. Together with other settlers in Maine, Martin fought for years for the right to the land he farmed, believing with the Liberty Men, as they called themselves, that Who can have better rights to the land than we who have fought for it, subdued it & made it valuable ... God gave the earth to the children? In 1801, settlers won the right to buy the land they farmed, but Martin was never able to pay for his and eventually lost it. In 1818, when he applied for a pension under the first general pension law passed by Congress for veterans in reduced circumstances, he testified, I have no real or personal estate, nor any income whatever.... I am a laborer, and by reason of my age and infirmity, I am unable to work. My wife is sickly and rheumatic. I have five children....

Martins poignant life story opens a window to a side of American history almost totally lost in the master narrative of the Revolution when it is told as a success story led by great men. Martin was not unusual, save for his ability as a writer. He was one of more than one hundred thousand young men, most of them landless, who saw military service in the Continental Army over the seven years of the war. Another one hundred thousand served in the militia, and several tens of thousands at sea. He was among the tens of thousands of veterans who applied for a pension in 1818, or in 1832. And he was like several thousand farmers in other states who for several decades after the war faced struggles to acquire or to hold on to land: the Green Mountain Boys in Vermont, the debt-ridden, tax-plagued rebels in western Massachusetts (among them Daniel Shays), Down-Renters in the Hudson Valley, the misnamed Whiskey rebels in Pennsylvania. Many would have shared a sense of the Revolution as not fulfilling its promises, as expressed by Herman Husband, leader of two backcountry rebellions in North Carolina in the 1770s and in western Pennsylvania in the 1790s that were both put down with force: In Every Revolution, the People at Large are called upon to assist true Liberty, but when the foreign oppressor is thrown off, learned and designing men assume power to the detriment of the laboring people.

As Martins words testify, ordinary people in the revolutionary era were far from being inarticulate or passive. Quite the contrary, they could be eloquent. As the participant-historian Dr. David Ramsay of South Carolina wrote in 1789, When the war began, the Americans were a mass of husbandmen [farmers], merchants, mechanics and fishermen, but the necessities of the country gave a spring to the active powers of the inhabitants and set them on thinking, speaking, and acting in a line far beyond that to which they had been accustomed.... It seemed as if the war not only required but created talents. One can say the same thing about ordinary people in the Revolution that the historian Ira Berlin said of freed African American men and women in the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction after reading thousands of their letters: under the pressure of unprecedented events, ordinary men and women can become extraordinarily perceptive and articulate.