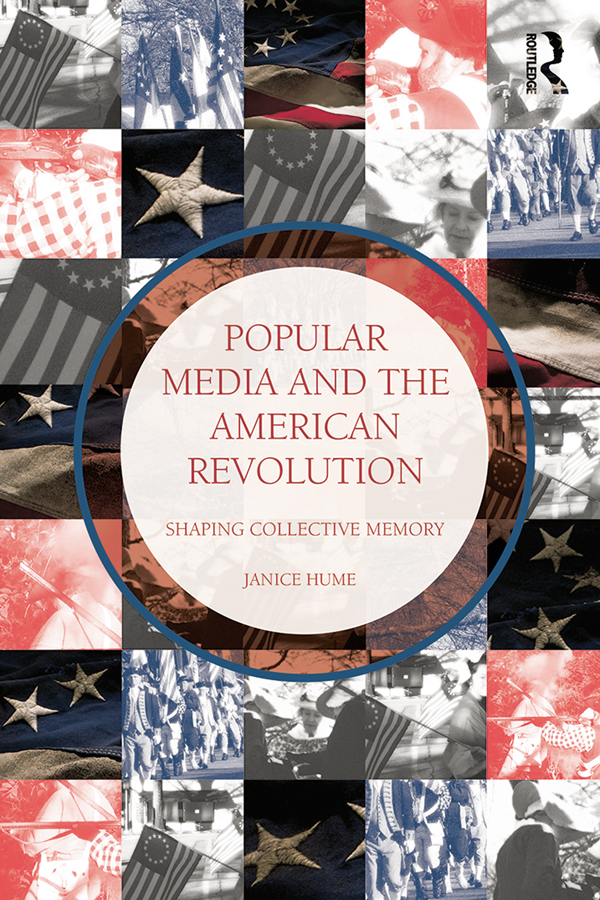

Popular Media and the American Revolution

The American Revolution an event that gave America its first real story as an independent nation, distinct from native and colonial origins continues to live on in the publics memory, celebrated each year on July 4 with fireworks and other patriotic displays. But to identify as an American is to connect to a larger national narrative, one that begins in revolution. In Popular Media and the American Revolution, journalism historian Janice Hume examines the ways that generations of Americans have remembered and embraced the Revolution through magazines, newspapers, and digital media.

Overall, Popular Media and the American Revolution demonstrates how the story and characters of the Revolution have been adjusted, adapted, and co-opted by popular media over the years, fostering a cultural identity whose founding narrative was sculpted, ultimately, in revolution. Examining press and popular media coverage of the war, wartime anniversaries, and the Founding Fathers (particularly, uber-American hero George Washington), Hume provides insights into the way that journalism can and has shaped a cultures evolving, collective memory of its past.

Janice Hume is a professor and head of the Department of Journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Obituaries in American Culture (University Press of Mississippi, 2000) and co-author of Journalism in a Culture of Grief (Routledge, 2008).

First published 2014

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2014 Taylor & Francis

The right of Janice Hume to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Portions of this book originally appeared as Building an American Story: How Early American Historians Used Press Sources to Remember the Revolution in Journalism History 37:3 (Fall, 2011), 172179.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hume, Janice.

Popular media and the American Revolution : shaping collective

memory / Janice Hume.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783. 2. Mass media and

historyUnited States. 3. Collective memoryUnited States. I. Title.

E209.H85 2013

973.38dc23 2013024171

ISBN: 978-0-415-53842-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-415-53843-5 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-203-10935-9 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

A number of people and organizations have supported this endeavor. I would like to thank, especially, the American Journalism Historians Association (AJHA) for the Joseph McKerns Research Grant Award which enabled me to spend a week in Washington, D.C., working at the Library of Congress. I treasure my friends and colleagues at the AJHA who inspire me and kindle my passion for history.

A heartfelt thanks, too, to the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia for giving me the gift of time, a semester-long research fellowship to finish this manuscript, and especially to Kent Middleton, longtime Journalism Department chair, who has always supported my work.

Thanks to Jere Morehead at UGA for Provosts Faculty Summer Support, to E. Culpepper Cully Clark, Jeff Springston, and Alison Alexander for their encouragement, to Sophie Barnes for her help, and to my great colleagues in the Journalism Department, who had to listen to a lot of musket fire and fife trilling as I worked on the last chapter.

Mary Miller, Peabody Awards Collection Archivist at the UGA Libraries, was of great help, as were reference librarians Diane Trap and Amy Watts, and kind people at the Library of Congress and the Mary Willis Library in Washington, Ga. Matthew Danelo and Allie Goolrick, graduate teaching assistants at UGA, helped with background material. I thank them for their good work.

Others whose suggestions, edits, or moral support have helped the cause: Bryan and Sharon Reber, Tanya Barrientos, Karen Russell, Carolina Acosta-Alzuru, Peggy Kreshel, Bonnie Bressers, Earnest Perry, Caryl Cooper, Carolyn Kitch, Patrick Cox, Fred Blevens, John P. Ferr, Jay Hamilton, Patrick Washburn, Lisa Burns, and, of course, Betty Houchin Winfield, who taught me how to do research.

Thanks to Erica Wetter, senior editor at Taylor & Francis, who saw the potential in this project. Thanks also to copy editor Gail Welsh, and to everyone at Routledge who contributed, including Emma Hkonsen, Gareth Toye, James Driscoll, and Simon Jacobs.

Finally, thanks to my family for encouraging me in my academic life, sister and brother-in-law Patsy and Steve Michael, brother and sister-in-law David and Ginger Hume, my niece and nephews, their spouses and kids.

A nation is much more than laws and borders. It is also stories, memories, and shared sentiment. To be an American is to connect with a larger national narrative, one that begins in Revolution. This book considers the story of Americas founding as told by national scribes, mainly journalists, throughout the centuries. It is not a history of the American Revolution, nor is it about how newspapers and magazines reported the battles and political squabbling as breaking news, to use a modern term the early printers wouldnt recognize. Many others have written about those topics. Rather, it is about how media have helped us remember and forget. Published and broadcast memories of the Revolution have contributed, and still contribute, to Americas identity. This is a book about Americas collective memory the beliefs we have about our past that shape our present and future and how that memory has manifested in popular media.

Why is the Revolution a worthy memory narrative? Formative periods are important to national identity. Sociologist Barry Schwartz has argued that the most significant moment in any societys past is its beginning, a period marked by the magic, attraction and prestige of origins.

American memory resides in part in the printed word. The United States was founded in an age of letters, centuries after Johannes Gutenbergs printing press heralded the European Renaissance and later the Age of Reason. We had presses, and thus newspapers, magazines, books, tracts, almanacs, and pamphlets, long before we had a Declaration of Independence and a Constitution. The press played a role from the beginning in building our American story, first by providing information during the years of conflict and later by recalling the Revolution as a significant event.

Many Americans learned their history through newspapers and magazines, noted Arthur Shaffer, who studied how the history of the Revolution was written prior to 1815. He pointed to era periodicals such as the Massachusetts Spy and Columbian Magazine that printed works of the earliest U.S. historians. Even though modern historians rarely cite Revolution-era news content as a basis for factual accounts of battles or leaders, they still use publications of the period to grapple with the nature of the Revolution, especially with the mindset of the colonists who declared their independence in 1776 and formed a new kind of government.