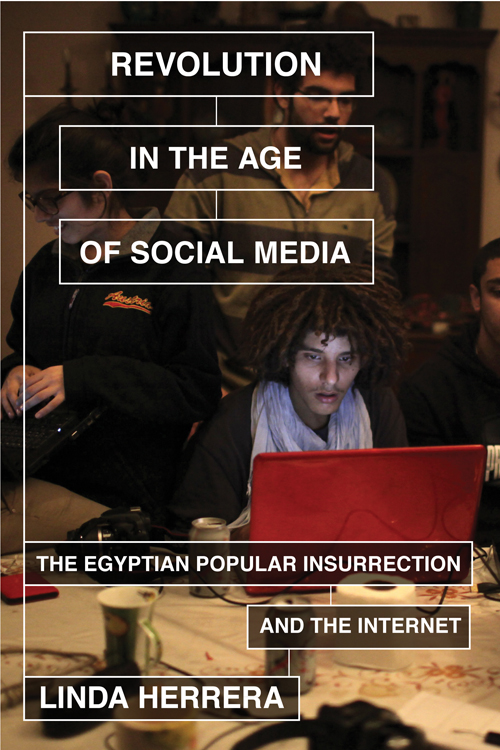

REVOLUTION

IN THE AGE OF

SOCIAL MEDIA

The Egyptian Popular Insurrection and the Internet

Linda Herrera

First published by Verso 2014

Linda Herrera 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-275-3 (PBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-276-0 (HBK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-277-7 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-647-8 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Herrera, Linda.

Revolution in the age of social media : the Egyptian

popular insurrection and the Internet / Linda Herrera.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-78168-275-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-78168-276-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-78168-277-7 (ebook)

1. EgyptHistoryProtests, 20112. Internet Political aspectsEgypt. 3. YouthPolitical activityEgypt. 4. Internet and youthPolitical aspectsEgypt. 5. Internet and activismEgypt. I.

Title.

DT107.87.H47 2014

962.055dc23

2014000584

Typeset in Minion Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

To the creative and courageous youth of Egypt who are engaged in an epic struggle to liberate their minds on the way to reimagining a new system for Egypt and the world

For last years words belong to last years language

And next years words await another voice.

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

Little Gidding, T.S. Eliot

Contents

T his book began as a fast book that turned into in a three-year odyssey. I first want to thank Ahmed Gaballah, a former student and research assistant from the American University in Cairo. He moved to California to work for Google where he helped develop the companys presence in the Middle East. He is now Senior Product Manager for Strategic Growth Markets at Adobe Systems. He introduced me to the inner workings of the Arabic web and walked me through techniques of online marketing. Together we read and reviewed the full 1,400-page printout of the We Are All Khaled Said Arabic Facebook page and worked together on , Marketing Martyrdom. I am truly grateful for his energy in getting this project off the ground and for his sense of adventure.

I met Mark Lotfy, a filmmaker and virtual creator, during a visit to Egypt in the early phases of researching this book. We shared a common interest in understanding the power struggles taking place in virtual spaces. Marks knowledge of the online culture wars, media theory, video games, and Egyptian popular culture is as astute and deep as anyones. We coauthored an article for Jadaliyya called E-Militias of the Muslim Brotherhood, and continued our collaboration by jointly writing . He has read and commented on many parts of this book.

I have spent countless hours online and in Egypt with activists, students, artists, and friends old and new, all of whom are always incredibly generous with their time and insights. I extend a special thanks to AbdelRahman, Kholoud, Haitham, Aly, Dalia, Nur, Hossam, Nourhan, Sherif, Ahmed, and the many Facebook friends who always keep me abreast of ever-changing developments in Egypt.

Some of the ideas for this book took early form as Jadaliyya articles. I extend a big thanks to the tireless coeditors at Jadaliyya, Adel Iskandar, Toni Alessandri, Hesham Sallam, and Ziad Abu-Rish, for their feedback and comments on various articles. Thanks also to Peter Mandaville, who offered valuable comments on an earlier version of .

I began my position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign just nine days before the start of the January 25 Revolution. I have since shuttled between Illinois and Egypt on a regular basis. I am grateful for the tremendous support I have received from the university. Special thanks goes to colleagues at the College of Education at Illinois and specifically at the colleges Department of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership, as well as to the Center for South Asia and Middle East Studies, and to my talented and eminently reliable teaching assistants, Fauzia Rahman, Garett Gietzen, Kevin Gitonga, and Ghassan Ibrahim, who have helped to keep me and my courses on track. Shiva, Tara, and Asef know how much I cherish their presence in my life.

I n his memoir, Revolution 2.0: The Power of the People Is Greater than the People in Power, Wael Ghonim makes a startling revelation about his interrogation at the hands of Egyptian State Security during the January 25 Revolution. Ghonim was an anonymous administrator (admin) of the Arabic We Are All Khaled Said Facebook page that issued the call for revolution. He figured it was only a matter of time before he would be discovered. When two State Security agents captured him on January 27, 2011, outside a trendy Cairo restaurant, Ghonim assumed it was because of his work on the page. To his surprise, the interrogators had no idea he was working as an admin. They were solely interested in his ties to his American dinner companions. Ghonim, Googles head of marketing for the Middle East, had been in a meeting with Jared Cohen, director of Google Ideas and formerly of the United States Department of State, and Matthew Stepka, Googles VP for Strategy. These were the last people Ghonim saw before disappearing for eleven days. He writes, Little did I know that this brief meeting would lead me to the most difficult experience of my life. On that same evening, Jared Cohen tweetedrather indiscreetly given the risks faced by activists on the ground at the timeFor reliable on the ground resources in #Egypt (#jan25) follow @Ghonim @EgyptUpdates @alshaheeed. Alshaheeed, The Martyr, was the Twitter handle for the We Are All Khaled Said page.

Ghonim recounts being blindfolded and taken away to an undisclosed location. During the interrogation, he was horrified to realize his questioners were trying to link him to the CIA. They were especially concerned about his relationship to Jared Cohen. Ghonim tries to downplay the State Security interest in Cohen by writing, I didnt find it strange that they specifically asked about Jared. His Jewish-sounding name could raise eyebrows in Egyptian State Security, given the long-standing Arab-Israeli conflict. Ghonims attempt to brush off questions about Cohen as mere sensitivity to a name is disingenuous at best. Cohen had held key positions in the State Departments internal think tank, Policy Planning, under both the Bush and Obama administrations. He had been pursuing a policy that can be called cyberdissident diplomacy (CDD) by reaching out to tech-savvy youth in the sixteen-to-thirty-five age range with the aim of training them in particular forms of cyberdissidence and online campaigning. Cohens forte was building networks among young Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. In 2010 he left the State Department to direct Google Ideas, where he specializes in finding technological approaches to counter-terrorism and counterradicalism.