This electronic edition published in 2020 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

One Rockefeller Plaza, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10020

www.aucpress.com

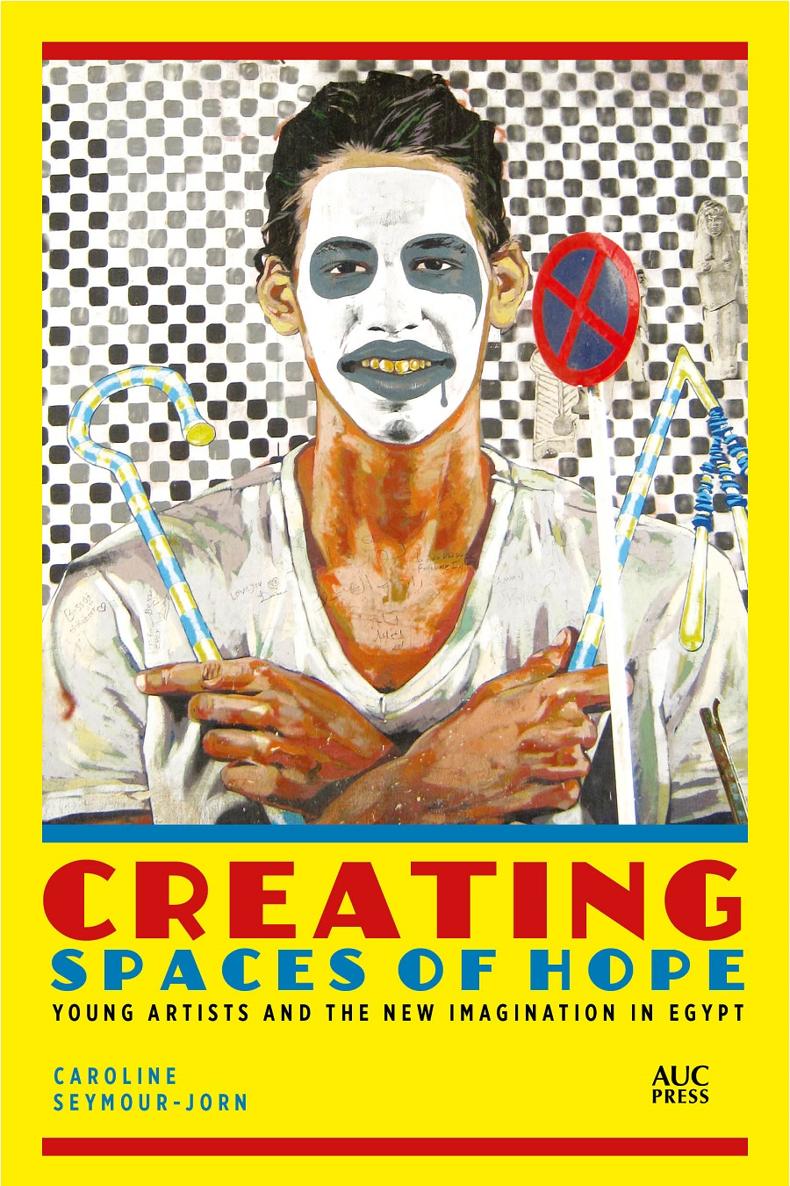

Copyright 2020 by Caroline Seymour-Jorn

An earlier version of chapter 1 appeared as Singing a New Future: Egypts Choir Project, in Middle East Critique 29, no. 2 (2020). Reproduced by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 974 8

eISBN 978 164 903 011 5

Version 1

This book is dedicated to Egypts young artists and activists, and to my family, Michael, Eva, and Leah.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a debt of gratitude to the artists and authors whose work I explore in this book. They generously shared their time and energy with me, speaking about their creative works, their personal and creative development, and their participation in Cairos artistic and literary world. I especially wish to thank Etidal Osman for a long friendship, generous hospitality, and intellectual engagement. Her ideas about the new imagination in youth writing in Egypt helped me develop my ideas about the creative spaces of hope that young artists of all types are creating in this dynamic but troubled city. I am deeply grateful to Robin Pickering-Iazzi for her enthusiastic support of my research and unflagging encouragement of my academic endeavors. I also wish to acknowledge crucial support from several funding sources and research centers at the University of WisconsinMilwaukee. I would like to thank Richard Grusin and Kennan Ferguson of the Center for Twenty-first Century Studies and the participants of the 2015 Center cohort, including Bernard Perley, Kimberly Blaeser, Katherine Paugh, Kristin Pitt, and Deborah Wilk, for helpful comments on parts of this manuscript. Support from Jasmine Alinder and the Letters and Science Humanities Scholarly Activities Fund, the Provosts Office, the Center for International Education, and the Global Studies Program allowed me to make regular research trips to Egypt over the past twenty years. I will be eternally grateful to my colleagues Anna Mansson McGinty, Kristin Sziarto, and Dalia Gomaa for their friendship, intellectual energy and collegial support throughout the years that I worked on this project. I would also like to thank Jenny Peshut for her enthusiasm and cheerful support of my endeavors in teaching and research. I am so happy to have had the chance to work with members of the AUC Press: Anne Routon encouraged me to move forward with the publication of this work, and Laura Gribbon carefully edited the final manuscript. Finally, I wish to thank my husband, Michael Jorn, for many thoughtful discussions about Egypt and creativity, and for being my companion through many journeys, both geographic and personal.

INTRODUCTION

J anuary 25, 2019 marked the eighth anniversary of the Egyptian Revolution that toppled President Hosni Mubarak and ended his thirty years of draconian autocratic rule. Since that time, Egypt has experienced massive street protests, clashes between supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood and other religious and secularist parties and government forces, three heads of state, significant constitutional changes, an Islamist insurgency in the Sinai desert, and a number of terrorist attacks of varying size and impact. Even as I write this introduction, new protests are taking place on the streets of Egypts cities, as people level charges against the al-Sisi regime. However, throughout these years of transition and unrest, Egypts ever-vibrant artistic world has continued to operate. Indeed, in the larger regional context, the uprisings that occurred throughout the Arab world as a result of the Arab Spring included a florescence of artistic activity.

In 2012 Professor of Arabic Literature Samia Mehrez argued:

One of the most remarkable accomplishments of the various uprisings in the Arab world since January 2011 has been the radical transformation of the relationship between people, their bodies, and space; a transformation that has enabled sustained mass convergence, conversation, and agency for new publics whose access to and participation in public space has for decades been controlled by oppressive, authoritarian regimes. (Mehrez 2012, 14)

In the early years after the 2011 Revolution, one way in which this new freedom was marked in Egypt was with graffiti and street art, public performance art, and studio art exhibitions, in which Egyptians claimed space for themselves, expressing their relationship to the state and to international entities that have so profoundly impacted Egypts politics and economy.

More recently the regime of President Abd al-Fatah al-Sisi has brought new forms of oppression to bear upon the artistic and cultural scene in Cairo. Al-Sisi took office in June 2014 and his regime has authorized the harassment and arrest of many young activists, journalists, writers, artists, and others critical of his presidency. During my research in Cairo in July 2015, one young artist expressed his dismay and surprise that al-Sisi had achieved a new level of oppression far beyond that of the Mubarak regime. This includes arresting and summarily executing activists and protesters and shutting down NGOs. There is to this day a continued hush over Cairos creative spaces, cafs, and intellectual discourse. As one activist and writer put it to me in early 2018, Its like walking on eggshells; you have to be careful who you talk to and what you say. Other writers and artists I spoke to expressed fear of delivering any sort of political critique in their creative production. At the same time, the art world still has a strong and active presence in downtown Cairo, though some of the gathering points and art exhibition sites seem to be shifting and changing, and peopleyoung people in particularare very aware of heightened surveillance of their activities and gathering spots, particularly in and around Tahrir Square.

This book explores innovative artists and writers in the Arab worlds most populous country and the way in which they engage, contest, and struggle with a postrevolutionary Egyptian modernity. Most of these creators are considered members of al-jil al-jadid (the new generation) or al-jil al-shabab (the youth generation) of creative producers in Egyptindividuals who are in their twenties or thirties, although a few are in their forties. They are all generating innovations in their fields of painting, sculpture, graffiti, or lyrical and literary production. Because I focus on works from 2010 until 2018, this book is not primarily about revolutionary art, nor does it focus only on what Marwan Kraidy calls creative insurgency, although a few of the works discussed herein are characterized by the mixture of activism and artistry characteristic of revolutionary expression (Kraidy 2016, 5). Rather, I discuss works that address a wide range of topics and explore how art and creativity have developed and become a part of a critical discourse about creativity and its relationship to society before, during, and after the events of January 25, 2011. This discourse circulates in the creative community, traditionally defined as arts and literary circlesthe people who attend to, critique, and acquire art and literary production. However, it also includes a new, broader public, a generation of young people who are involved in or view new forms of creative production including collaborative music and theater production, and street or public art.