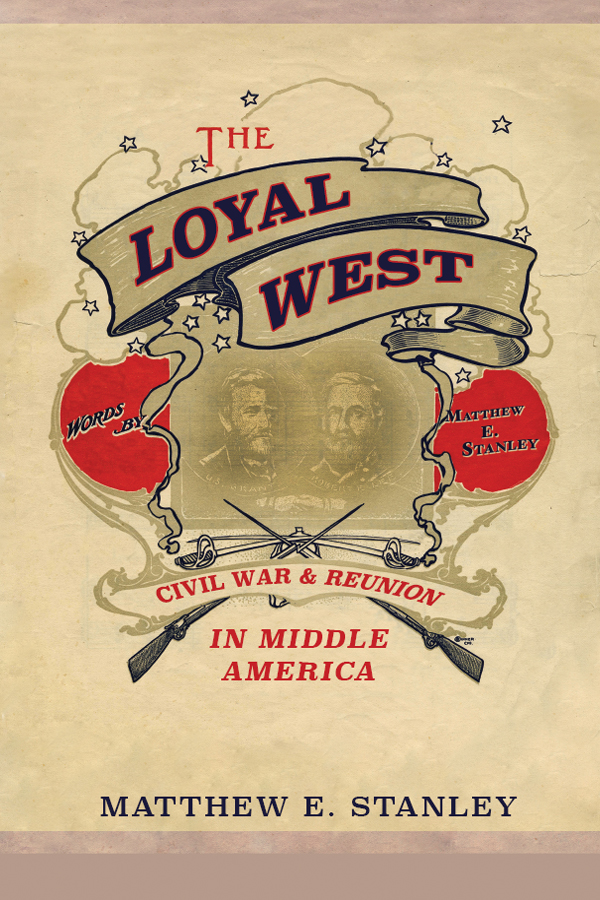

THE LOYAL WEST

Civil War and Reunion in Middle America

MATTHEW E. STANLEY

2017 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stanley, Matthew E., author.

Title: The loyal west: Civil War and reunion in middle America / Matthew E. Stanley.

Description: Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016023983 (print) | LCCN 2016042772 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252040733 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252082245 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252099175 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ohio River ValleyHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects. | Reconstruction (U.S. history, 18651877)Ohio River Valley. | BorderlandsOhio River ValleyHistory19th century. | IllinoisHistory, Local19th century. | IndianaHistory, Local19th century. | OhioHistory, Local19th century. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects.

Classification: LCC F518 .S73 2016 (print) | LCC F518 (ebook) | DDC 977/.02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016023983

FOREWORD

Research is me-search, as the expression goes. So goes this book. Most of my ancestors were plain folk who migrated to southern Illinois in the nineteenth century from North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky. This study is in part my modest attempt to connect the protracted stories of families like mine with the southern Illinois I knew growing upa place rich in hospitality with a strong sense of kinship, community, and local identity, but also a somewhat closed place of striking racial and religious uniformity, political and cultural homogeneity, conservative evangelicalism, and both racial exclusion and clear hierarchies of whiteness. The latter inclinations give me the most pause. They always have.

This work is also, I think, part of a national story. As American historians, we have reached a practical impasse as a field; as Americans, we have reached an intellectual disconnect as a community. Scholars do not debate that slavery was the crux of the Civil War, that race played a significant role in how white Americans North and South remembered the conflict, or that a racialized memory acted in mutuality with Jim Crow going into the twentieth century. Today, a century and a half after Appomattox and fifty years after Selma, social scientists have unassailable evidence of how slavery and its legal, social, and cultural outgrowths continue to shape the material and psychological world we inherited. Chattel bondage is the mother of afflictions. Convict-leasing, lynching, ghettoization, red-lining, block busting, white flight, fraud, rape, murder, and racial disparities in everyday American life, from employment to healthcare to education to the criminal justice system, are her grievous children. This is to say nothing of the profusion of scholarship addressing how our national mechanisms (historical and contemporary) of militarism, nationalism, capitalism, and state and individual violence both hasten environmental destruction and reinforce class, gender, ethnic, religious, and, of course, racial prejudice and inequity. Yet our current debates over the historian's task and the public imperative of our work come, as they always do, in an era when the line between the past we study and the present we live is, at times, excruciatingly direct. As I finish this work on the construction of whiteness and the legacy of the Civil War in Middle America, it is clear yet again that the task of that war has been left painfully unfinished. Here, at the tail end of the war's sesquicentennial, and in the wake of a racially motivated massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, American publics are once more questioning the cause of the conflict and debating the meaning and appropriateness of its symbols. The war's anniversary and the tragic theater of the news cycle have generated a new and reciprocal, if not always productive, dialogue. Questions of institutional inequality owing to centuries of discrimination continue to loom large, particularly along slavery's former border and, most suitably, in the Loyal West itself. Through social strife brought on by longstanding structural racism and triggered by specific acts of injustice in places like Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore, Maryland, we are reminded that, like individuals, we as a society cannot escape our past; it is present in all we do.

I offer no sweeping predictions. My only hope is that this work might, in some small way, contribute to our understanding of how we got to where we are and help us confront the tragic burdens of history we see so palpably before us. As William Faulkner, eminent wordsmith and analyst of the American racial psyche, contended, Yesterday won't be over until tomorrow, and tomorrow began ten thousand years ago. In 2016 America, tomorrow sometimes seems impossibly far off.

The University of Illinois Press

is a founding member of the

Association of American University Presses.

____________________________________

University of Illinois Press

1325 South Oak Street

Champaign, IL 61820-6903

www.press.uillinois.edu

The Lower Middle West in 1860.

INTRODUCTION

THE GEOGRAPHY EMBODIED

Loyal Westerners in War and Peace

I am the Ohio River,

From the north I beckon to brooks, creeks, rivers in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

Countless are the other streams flowing from east, south, and north as they come to join me.

You have used me to fight your wars, as a barrier between North and South, as a boundary between some of your richest states.

If rivers carry the life blood of a continent, then I am an artery to the heart of America.

J. Robert Smith, Evansville Sunday Courier and Press, August 12, 1962

The terms of peace were far from settled, the ink on the surrender documents was barely dry, and the battle over the meaning of the war that had just been fought was only beginning when in 1865 John W. Barber and Henry Howe published The Loyal West in the Times of the Rebellion at their Main Street offices in downtown Cincinnati. The Queen City of the West had been riven by racial and ethnic strife during the antebellum period and bedeviled by political faction during the war itself. Now, having won the late conflict, its victorious residents required a consensus narrative, one from the perspective of native white Unionists looking to make sense of their role in the struggle to preserve the republic. Intending the volume to become a household book for the Western people, the authors distinguished the Loyal West from the pre-war West of contiguous slaveholding and non-slaveholding states centered on the Ohio River Valley. Though the West was staunchly Unionist, they explained, the word West is not. We here apply the title to those States of our Country's West which in the Rebellion were faithful to the Union. Though Barber and Howe employed regional allegorywestern heroes amid bountiful prairies and idyllic river valleys

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.