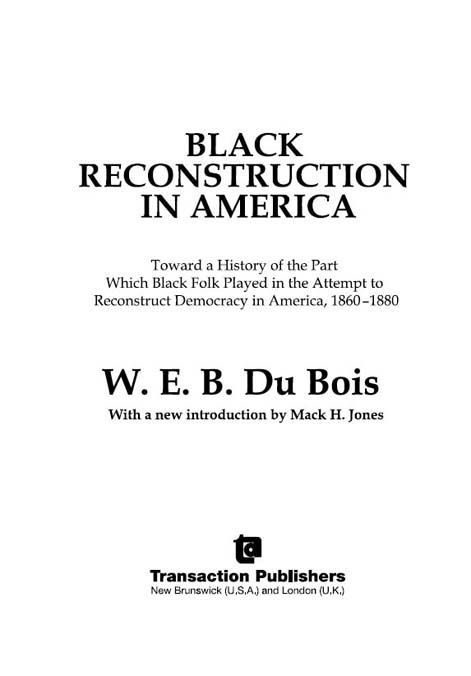

First Transaction printing 2013

Originally published in 1935 by Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Introduction copyright 2012 by Transaction Publishers. Originally published in Black Politics in a Time of Transition, National Political Science Review, Volume 13, edited by Michael Mitchell and David Covin.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to Transaction Publishers, RutgersThe State University of New Jersey, 35 Berrue Circle, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854-8042. www.transactionpub.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2012021875

ISBN: 978-1-4128-4620-2

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 18681963.

Black reconstruction in America : toward a history of the part of which Black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 18601880 / W. E. B. Du Bois, with a new introduction by Mack H. Jones.

p. cm.

Originally published in 1935 by Harcourt, Brace and Co.

1. Reconstruction (U.S. history, 1865-1877) 2. African AmericansHistory1863-1877. 3. African AmericansPolitics and government. 4. African AmericansEmploymentHistory19th century. I. Title.

E668.D84 2012

973.8dc23

2012021875

Ad Virginiam Vitae Salvatorem

Contents

Introduction to the Transaction Edition

Mack H. Jones

Introduction

In my view, Dr. Du Bois was Americas most outstanding and socially significant intellectual ever, Black or White. His contributions as a scholar and political activist affected and enlightened practically every segment of American life and culture. For this paper, I choose to discuss his contributions to the development of Black or African American Studies. (Throughout the paper I use the two terms interchangeably.) Although the modern Black Studies movement did not begin until the 1960s, Du Bois made the case for Black Studies in the early days of the twentieth century and actually carried out Black Studies research long before the term was coined. In reality, Du Bois was the father, or perhaps, we might say, the intellectual grandfather of modern African American Studies. To support this assertion I will first identify some of the ideological assumptions and principles of the Black Studies movement and then demonstrate how they were reflected in the scholarship and political activism of Du Bois long before they were articulated by scholars such as Nathan Hare, Maulana Karenga, Molefi Asante, and others. Indeed, Du Bois not only addressed the assumptions and principles that were to characterize the Black Studies movement of the 1960s, but he also raised and expounded on almost all of the ideas and arguments that arose during the broader Black liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Arguments about integration vs. separation, nationalism vs. assimilation, socialism vs. capitalism, male chauvinism vs. feminism, etc., were all addressed by Du Bois half a century earlier. Du Bois not only addressed all of these issues, he did so with clarity and conviction unmatched by many contemporary scholars.

Biography

Knowing and understanding Du Bois biography and how it was shaped by the changing times in which he lived and struggled are critical for understanding his evolution as the intellectual grandfather of modern African American Studies. Given the often repeated assertion that he was an elitist, it is easy to forget that he was not from a privileged or middle-class family. He grew up in a single parent home and never really knew his father. His mother was a frail woman, a domestic who took in ironing from White folks to make ends meet. Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a town of some five thousand people including twenty-five to fifty Black folk, in 1868, only five years after the end of slavery. He and his mother attended a Congregationalist church where they were the only members of color. After graduating from high school in 1884 as the only Black student in the class, Du Bois entered Fisk in 1885 and graduated in 1888 as the top student in a class of five. While at Fisk for two summers he taught elementary school in rural Tennessee, and it was there that he developed his understanding of the place of Black people in American society. After graduating from Fisk, he entered Harvard in 1888 and received the BA cum laude in 1890 and the MA from Harvard in 1891. He pursued doctoral studies in Germany from 1892 to 1894 but did not receive the doctoral degree because he lacked one year in residence. Du Bois received the doctoral degree from Harvard in 1895. From 1897 to 1910 he served at Atlanta University. He left Atlanta University in 1910 and worked for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People NAACP where he served on the board of directors and edited the Crisis magazine; he resigned from the NAACP in 1934 and returned to Atlanta University as head of the sociology department. Du Bois was retired involuntarily by Atlanta University in 1944 and returned to the NAACP. In 1948, Du Bois was again dismissed from NAACP. After 1948, Du Bois continued to work with a variety of organizations opposed to war and Western imperialism. Du Bois moved to Ghana, West Africa, in 1961 and died there in 1963 while working on his final project, an encyclopedia of Africa.

Ideological Assumptions and Principles of the Black Studies Movement

Black Studies or African American Studies as an academic discipline in American education grew out of struggles of Black students of the 1960s on campuses of both historically Black and traditionally White institutions. During the 1960s students argued that mainstream or White scholarship was irrelevant for those interested in understanding and transforming the position of Blacks in American life because it grew out of the experiences of White or Euro-Americans and was grounded in the ideology of White supremacy. As a consequence, it was argued, mainstream scholarship raised questions and generated information that gave a distorted view of American society and the place of Black folk in it. To overcome this problem, advocates of Black Studies called upon Black scholars to challenge the assumptions of mainstream scholarship and develop new paradigms and frames of reference that would be grounded in the experiences of African people in the United States and around the world. These new frames of reference would ask different questions and generate information that would illuminate more clearly the nature of oppression and suggest more effective strategies for Black liberation.

Relevance, according to the proponents of Black Studies, was not merely an academic matter. Developing new paradigms and frames of reference and conducting research was only half of the responsibility. The other half involved applying this new knowledge in the struggle against racial oppression. To know carried with it the responsibility to do was the first principle of the Black Studies movement. Thus to satisfy the call for relevance, Black scholars had to be activists as well. There could be no separation between town and gown, between campus and community.

Next page