Copyright 2005 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

First paperback printing, 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reed, Christopher Robert.

Black Chicagos first century / Christopher Robert Reed.

p. cm.

Summary: Examines the first one hundred years of African American settlement and achievements in Chicago. It spans the antebellum, Civil War, Reconstruction, and post-Reconstruction periodsProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN13: 978-0-8262-2128-5 (paperback : alk. paper)

1. African AmericansIllinoisChicagoHistory19th century. 2. African AmericansIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 3. Chicago (Ill.)History19th century. 4. Chicago (Ill.)History 20th century. 5. Chicago (Ill.)Race relations. I. Title: Black Chicagos 1st century. II. Title.

F548.9.N4R437 2005

977.3'1100496073dc22

2005006294

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Designer: Stephanie Foley

Typefaces: Goudy and Ottomat

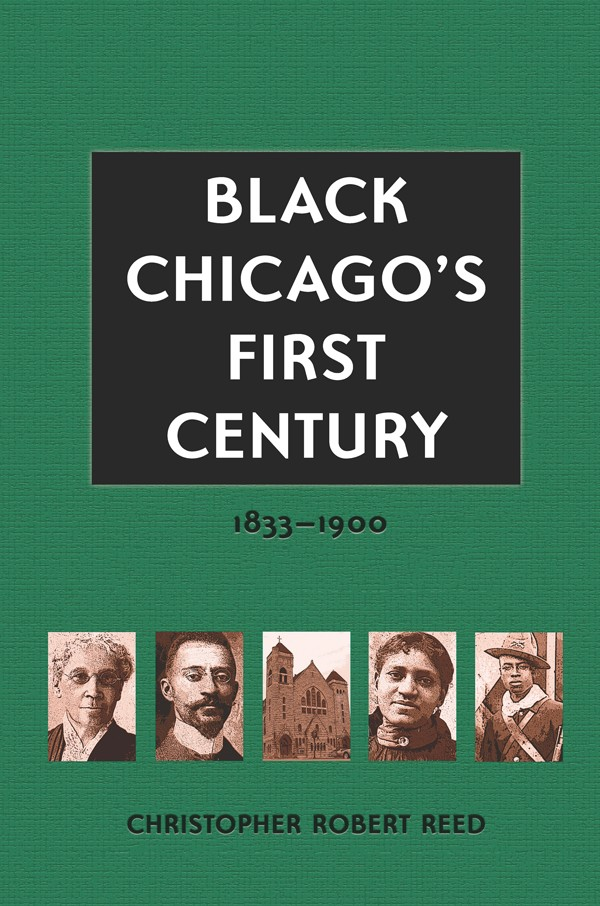

Jacket photos: Center, Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church (courtesy of Quinn Chapel A.M.E.); Left to right, Mary Richardson Jones, Dr. A. M. Curtis, and Mary Davenport (Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, Chicago Public Library), and A. D. E. Jackson (Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library).

ISBN-13: 978-0-8262-6460-2 (electronic)

Acknowledgments

THIS PROJECT could never have been completed in the form it finally assumed without the personal interest and cooperation, along with the professional commitment, of a score or more of individuals and institutions. Direct bloodline descendants of several of the oldest African American settler families of Chicago as well as the spiritual and intellectual heirs of the Old Settlers shared memories, written material, photographs, and other memorabilia contributed mightily to the production of Black Chicagos First Century, 18331900. This roll of major contributors includes the following: Grace Mason and Michelle Madison of the Atkinson family, Leota Johnson from the Taylor family, Jeanne Boger Jones from the Hall family, and Lloyd C. Wheeler, III, from the Jones and Wheeler families.

For their professional assistance over the last decade, I wish to thank Michael Missick and the staff at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.; Mark Sorenson, Greg Cox, and Kim Efrid at the Illinois State Archives in Springfield; Anita Haskell at the Murray-Green Library at Roosevelt University, along with technical assistance from Ronald Elms and Len Redmond in Office Services; Robert Miller and Michael Flug and staff at the Vivian G. Harsh Collection at the Carter G. Woodson Center of the Chicago Public Library, as well as Teresa Yoder and other staff at the Harold Washington Center of the Chicago Public Library; John Hoffman and James Cornelius at the Illinois Historical Survey and Lincoln Room at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Emeritus Professor William Andrews of SUNY-Brockport; Elaine Schwanekamp at the Chautauqua County Historical Society in Westfield, New York; Linda Evans and the staff of the Chicago Historical Society; and the staff of the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago.

For the unbridled enthusiasm and critical review of all or parts of the book from and beyond the academy, I wish to thank Lynn Y. Weiner, Brigitte M. Erbe, Robert T. Starks, Dennis Dickerson, Suellen Hoy, Laura Janota, John Bracey, Jr., Deirdra Ann Lucas, Vinton Thompson, and Dr. Adelaide Cromwell of Brookline, Massachusetts, as well as Lerone Bennett, Jr., Sharon Vaughn, Jerolyn Croswell, Marionette C. Phelps, Muriel Wilson, Elizabeth Glasco, Lynn Von Dreele, Cherie Pleau, Lynnett Davis, and the homeschooled family of Jonathan and LaShone Kelly.

The local clergy informed and contributed also in reconstructing this saga of a spirit-driven people. I extend my appreciation to Rev. Anthony Vinson, Sr., along with Luster and Olavenia Jackson of Bethel A.M.E. Church; Rev. James A. Missick of the Original Providence Baptist Church; Rev. James M. Moody of the Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church; Rev. A. Lincoln James of the Greater Bethesda Baptist Church; and Father Martini Shaw of the St. James Episcopal Church.

Captain DeKalb Wolcott, II, of the Chicago Fire Department, and fire department historians Ken Little and Father John McNalis, along with Patti Thomas, president of the African American Film and TV Makers, helped shape the story of black firefighters.

The role of the sergeant in the military hierarchy gained greater importance in my way of thinking as I examined the content of Civil War records and conferred with Tech. Sgt. Albert A. Burns, Seventh U.S. Army (a veteran of World War II) and Sgt. Malcolm M. Reed, Fourth Marine Division (a veteran of Gulf War I).

Graduate students at Roosevelt University deserve mention for their insightful views and inquiries. Those who participated in lively discussions both inside and outside the classroom of History 465 (The History of Black Chicago) about the validity of ideas and interpretations presented in Black Chicagos First Century included Clinton P. Walker, Janice Collier, Curtis Keyes, Jr., Nick McCormick, Ronald T. Jones, Eve Bady, Susan Bova, and Terrence Henderson.

Special thanks to my wife, Marva P. Reed, who spent many hours at the National Archives scouring veterans records for possible useful data on Chicagos black Civil War heroes. Of course, all errors in interpretation and presentation rest on my shoulders alone.

Extra-special thanks go to my editor at the University of Missouri Press, Julie Schroeder, who personified acuity of mind and eye as she elevated copyediting to a fine art form. In her perseverance in this task, she demonstrated a bonding with the author that will not be forgotten. Further, I also wish to thank the presss director and editor-in-chief, Beverly Jarrett, and acquisitions editor Clair Willcox, for considering this manuscript, for at times it must have appeared an impossible burden rather than a blessing.

The late nineteenth century in black history is indeed a stretch of undiscovered territory, and from it this project will surely bear productive fruit.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.