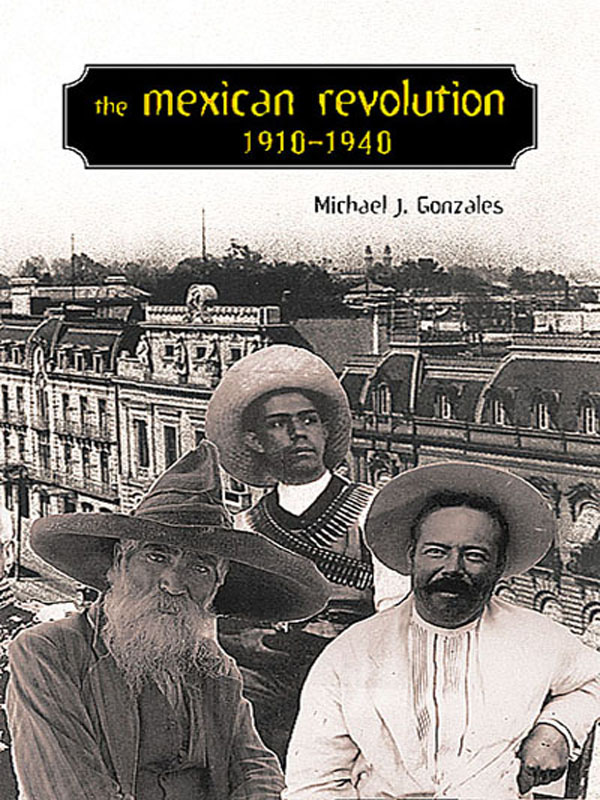

the mexican revolution, 19101940

A SERIES OF COURSE ADOPTION BOOKS ON LATIN AMERICA:

Independence in Spanish America: Civil Wars, Revolutions, and Underdevelopment (Revised edition)Jay Kinsbruner, Queens College

Heroes on Horseback: A Life and Times of the Last Gaucho CaudillosJohn Chasteen, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Life and Death of Carolina Maria de JesusRobert M. Levine, University of Miami, and Jos Carlos Sebe Bom Meihy, University of So Paulo

The Countryside in Colonial Latin AmericaEdited by Louisa Schell Hoberman, University of Texas at Austin, and Susan Migden Socolow, Emory University

Que vivan los tamales! Food and the Making of Mexican IdentityJeffrey M. Pilcher, The Citadel

The Faces of Honor: Sex, Shame, and Violence in Colonial Latin AmericaEdited by Lyman L. Johnson, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Sonya Lipsett-Rivera, Carleton University

The Century of U.S. Capitalism in Latin AmericaThomas F. OBrien, University of Houston

Tangled Destinies: Latin America and the United StatesDon Coerver, TCU, and Linda Hall, University of New Mexico

Everyday Life and Politics in Nineteenth Century Mexico: Men, Women, and WarMark Wasserman, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Lives of the Bigamists: Marriage, Family, and Community in Colonial MexicoRichard Boyer, Simon Fraser University

Andean Worlds: Indigenous History, Culture, and Consciousness Under Spanish Rule, 15321825Kenneth J. Andrien, Ohio State University

The Mexican Revolution, 19101940Michael J. Gonzales, Northern Illinois University

SERIES ADVISORY EDITOR: LYMAN L. JOHNSON,

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHARLOTTE

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8263-2781-9

2002 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved.

First edition

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Gonzales, Michael J., 1946

The Mexican Revolution, 19101940 /

Michael J. Gonzales. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Dilogos)

ISBN 0-8263-2779-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-8263-2780-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. MexicoHistoryRevolution, 19101920.

2. MexicoPolitics and government19101940.

i. Title. ii. Dilogos (Albuquerque, N.M.)

F1234 .G6248 2002

972.08'2dc21

2001005644

For Michael and Ben

CONTENTS

ONE

General Porfirio Daz and the Liberal Legacy

TWO

Crisis and Revolution

THREE

Counterrevolution

FOUR

Northern Revolutionaries and the Fall of Huerta

FIVE

Power Struggle

SIX

Carranza in Power

SEVEN

Alvaro Obregn and the Reconstruction of Mexico

EIGHT

Plutarco Elas Calles and the Revolutionary State

NINE

Lzaro Crdenas and the Search for the Revolutionary Utopia, 19341940

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Lyman Johnson and David Holtby encouraged me to write this book, and Lymans editorial comments improved the final product. I appreciate the support of the History Department, the Center for Latino and Latin American Studies, and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Northern Illinois University. Terry Sheahan worked as my research assistant and helped me gather information about the Mexican Revolution. She also drew the maps for the book.

I am grateful to my mother, Betty A. Owen, for working hard to provide for her children and for placing their interests before her own. My wife, Gail, has accompanied me on research trips to Latin America, sometimes with young children in tow, and has always encouraged my research and writing. Her support is greatly appreciated. Our children, Michael and Ben, have been a constant source of pride and joy.

I would also like to remember my younger brother, Dave. I think that he would have liked the book.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

TABLES

MAPS

FIGURES

INTRODUCTION

I N the 1880s the Noriega brothers, two Spaniards living in Michoacn, Mexico, purchased a marsh from the town leaders of the village of Naranja. For centuries, the marsh had nourished villagers with fish, waterfowl, mussels, and crustaceans and had provided them with reeds to weave into straw mats and braids to sell in local markets. The Noriegas drained the marsh, developed a highly productive maize hacienda, and exported the corn to eastern markets via newly constructed railroads. They became wealthy and politically influential members of the regional elite. Naranjeros, meanwhile, lost their economic self-sufficiency. They suffered malnutrition. They could not buy shoes or clothing for their children. They struggled to find the money to hold religious festivals central to their cultural identity and spiritual consciousness. To survive, they worked on the Noriegas estates or migrated to labor on unhealthy sugarcane plantations.

The plight of Naranjas peasants was replicated elsewhere in Mexico in areas where geographic and ecological conditions favored cultivation of cash crops in demand at home and abroad. Widespread loss of land created an economic crisis for peasants, whose desperation led them to take up arms against the seemingly impregnable regime of General Porfirio Daz, dictator of Mexico since 1876. Regional agrarian movements spearheaded the overthrow of the dictatorship in 1911, an improbable historical event known as the Mexican Revolution.

Unregulated capitalist development and political centralization contributed to Dazs downfall. The government facilitated hacendados acquisition of village land and ignored peasants plight. Moreover, the dictator, judging domestic sources of capital inadequate to generate development, offered foreign investors attractive incentives to start businesses in Mexico. Capital flowed into the country, particularly from the United States, without institutional safeguards to protect national sovereignty. The preeminence of foreign ownership over key industries became controversial and created discontent, especially among provincial elites and workers.

The Daz governments centralization of authority also ruptured traditional patronage networks and systems of social control. Loss of political autonomy outraged notables and villagers alike. British historian Alan Knight has called local-level revolutionary movements of primarily political origin, prominent in northern Mexico and isolated regions, serrano revolts.

In 1910, Mexicos ruling elite bungled the politics of presidential succession and created an opportunity for organized political opposition to form. Could the revolution have been avoided if elites had remained united against the masses? Given the breadth and depth of the agrarian crisis, this seems doubtful. Even after the fall of Daz, agrarista movements persisted until the land had been redistributed or agrarians had been defeated.

The popular and agrarian character of the revolution makes it a social revolution. The conflict pitted landless peasants, elements of the working classes, and discontented provincial gentry against the dictator Daz, his elite supporters, and the federal army. The revolution threw out the old guard, reinvented the state, and made possible historic social and economic reforms. The revolutionary state gave landless peasants hundreds of thousands of hectares of land, nationalized foreign-owned petroleum companies, and significantly expanded public education. If the final outcome failed to eradicate poverty, create democracy, or achieve economic independence, the event still remains revolutionary.