This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana

47404-3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2012 by Hillel Bardin

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bardin, Hillel.

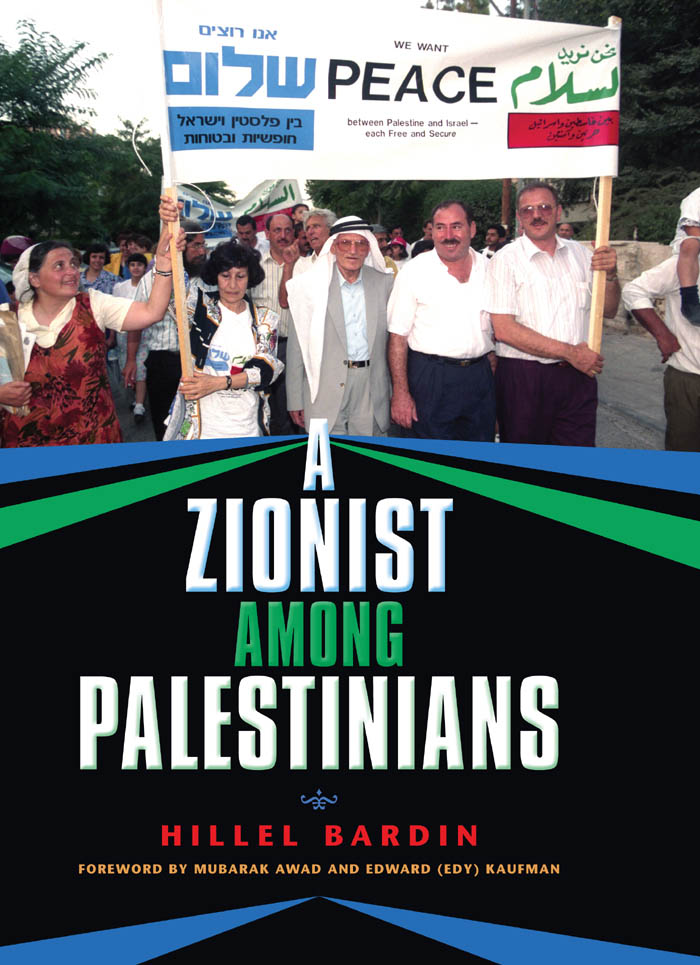

A Zionist among Palestinians / Hillel Bardin ; foreword by Mubarak Awad and Edward (Edy) Kaufman.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-253-00211-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-253-00223-5 (ebook)

1. Arab-Israeli conflict1993Peace. 2. Arab-Israeli conflictSocial aspects. 3. Conflict managementIsrael. 4. Palestinian ArabsCivil rights. 5. Peace-buildingIsrael. 6. Nonviolence. I. Title.

DS119.76.B37 | 2012 |

956.94054dc23 | 2012005739 |

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13 12

TO MY WIFE , Anita

TO MY COMMANDER , Shammai Shpitzer

TO MY FRIEND , Jalal Qumsiyeh

FOREWORD

Mubarak Awad and Edward (Edy) Kaufman

The timing of this publication is particularly important. The wave of non-violent struggle in the Middle East and northern Africa for democracy, human rights, and dignity has already resulted in regime change in a few countries. While authoring these lines, we have been deeply interested in the possibility that Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza might join in the struggle. If that happens, what will be the reaction of Israeli Jews? Will they work across the divide with Arabs who share such values? The personal story of Hillel, whom we know from the days of the First Intifada, is not only a testimony, but also a source of inspiration for both our societies. At the same time, the human dimension of the experiences he describes should move not only those in the Arab and Jewish diasporas, but all others keen to understand the obstacles and potential impact of nonviolent struggle in one of the worlds most protracted and aggressive conflicts.

For the sake of transparency, we should mention that this foreword has been written by a Palestinian and an Israeli, both of whom have been involved in furthering the nonviolent struggle to end Israeli occupation and search for a just peace. Since the First Intifada, we have spent a considerable part of our lives in advancing this strategy: Mubarak worldwide, as chair of Nonviolence International and as a teacher; and Edy in academic scholarship, applying the results of his research through activism in human rights organizations and by facilitating conflict transformation workshops. We both befriended Hillel and were participants in some of the stories covered in this book.

Moving from the individual to the collective narrative, we humbly believe that our contribution can best serve the reader not just by adding our personal experiences, but by also illuminating the wider context within which the stories in the book took place. From the June 1967 war until the end of 1987, resistance to occupation was conducted by small groups of armed fighters who were trained outside the area and carried out lethal attacksagainst civilian targets in Israel proper, the settlements in the occupied territories, and abroad (e.g., airplane hijackings and the killing of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics). Israeli retaliations and often preemptive punitive actions against unarmed civilians amounted at times to what could be considered state terrorism.

Not a few argue that the Palestinians have tried nonviolence before, with only partial success, during the First Intifada. If it didnt work then, whats the point in trying it again? Indeed, primarily nonviolent methods were utilized during that uprising, a most significant change compared with the previous period. Moderation was evident not only in the means of protest but also in the successful efforts by Palestinians under occupation to put pressure on the PLO to move from formulas such as a democratic and secular Palestine to a two-state solution, an Israeli and a Palestinian state living peacefully next to each other. However, certain elements of the First Intifada prevented it from constituting a true and completely peaceful resistance movement. It was spontaneous, only partially organized, and had a grassroots, widely shared leadership, but it lacked a clear, top-down message of endorsement of this form of popular civil disobedience. Hence, the lessons learned from previous weaknesses should be important now that this form of action is becoming widely accepted as effective.

There are some structural reasons for the breakout of the intifada in December 1987, including the deterioration of the economic situation and growing unemployment amid the Israeli economic crisis; a generation of university graduates that could not find sources of income except in menial jobs; and the stagnation of the appeal for summudsteadfastnesswith the policy of crippling annexation through the establishment of more Jewish settlements. The trigger was an unplanned protest against the accidental deaths caused by an army truck driver colliding with two cars in Gaza. Palestinians gathered at first spontaneously, and then became mobilized under directives into massive protests across the Palestinian territories, blocking roads and Israeli army movements. Demonstrators threw stones at the Israeli soldiers despite the tear gas and rubber-coated bullets used in return. Massive funeral processions also demonstrated nonviolent resistance to Israeli occupation. The bottom-up nature of the uprising can be recognized not only through the political parties represented in the PLO but increasingly by the emergence of NGO s advocating the organizing of resistance and nonviolent actions. Much of the story has been covered by Mary King (2007), Maxine Kaufman-Lacuste (2010), and others. What is important to our analysis is that many individuals and organizations at that time advocated the involvement of Israeli activists in their struggle. And Hillel Bardin was eagerly trying to reach out from the Israeli side.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.