COLOR AND CHARACTER

COLOR AND CHARACTER

West Charlotte High and the American Struggle over Educational Equality

PAMELA GRUNDY

THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the Z. Smith

Reynolds Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2017 Pamela Grundy

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Jacket illustration: detail of West Charlotte High School class of 1987 from the school yearbook, The Lion. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library.

All student portraits appearing on chapter-opening pages from the West Charlotte

High School yearbook, The Lion. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Grundy, Pamela, author.

Title: Color and character : West Charlotte High and the American struggle over educational equality / Pamela Grundy.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015392| ISBN 9781469636078 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469636085 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: West Charlotte High School (Charlotte, N.C.)History. | Educational equalizationNorth CarolinaCharlotteHistory. | School integrationNorth CarolinaCharlotteHistory. | African AmericansEducation (Secondary)North CarolinaCharlotte. | Charlotte (N.C.)Race relations.

Classification: LCC LC213.23.C4 G78 2017 | DDC 373.09756/76dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015392

To everyone who loves

WEST CHARLOTTE HIGH SCHOOL

For further information on this book,

visit www.colorandcharacter.org.

CONTENTS

FIGURES AND MAPS

FIGURES

West Charlottes first building, 1938

Newspaper staff and journalism class, 1946

Teachers, 1952

West Charlottes founding principal, Clinton Blake, 1947

Basketball team, 1946, and majorettes, 1957

Marching band, 1969 38

Dorothy Counts at Harding High School, 1957

Driver education class, 1966

Science students, 1965, and tailoring students, 1964

Students cheer at a pep rally, 1969

Yearbook headlines, 1971

The first integrated staff of the West Charlotte Lion, 1971

West Charlottes supporters march to save their school, 1974

West Charlotte students welcome Boston students, 1974

Mertye Rice and Sam Haywood, 1979

Sophomores at a pep rally, 1985

Two of West Charlottes distinctive cultural groupings, 1982

English as a Second Language students, 1986

Members of the sophomore council, 1989

State basketball championship celebration, 1992

Fall Carnival, 1995

Members of Students Against Violence Everywhere (SAVE), 2005

Principal Kenneth Simmons, 1997

Students, 2001

Homecoming celebration, 2005

Spencer Singleton and Jarris McGhee-Bey, 2001

Marching band at the Carrousel Parade, 2002

John Modest with students, 2008

Tribute to volunteer Mable Latimer, 2010

Yearbook staff, 2006

College-bound students, 2010

Marching band, 2015

MAPS

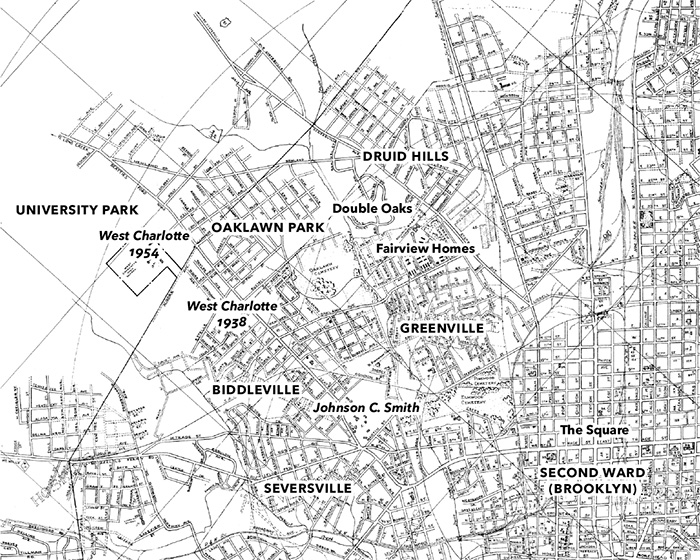

Map of Charlottes west side neighborhoods, 1954 xii

Map of central Charlotte showing highway construction and percentage of black population by census tract, 1970

Maps of Mecklenburg County showing percentage of black population by census tract, 1970 and 1990

COLOR AND CHARACTER

COLOR AND CHARACTER

Before the 1930s, many of Charlottes African American residents lived in the downtown Second Ward neighborhood known as Brooklyn. As the city expanded, African American families moved west to growing neighborhoods such as Greenville and Biddleville. Official Map of Charlotte, 1954. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room.

INTRODUCTION

When you feel as if you belong, as if you have a reason for being there, you feel protected. You feel encouraged. Thriving, existing, living vibrantlyyou feel encouraged to do that. And thats what I think West Charlotte provided for so many people.... You have evidence of people belonging to something, and being a part of something, and not having to make excuses for it. And you can see how the human spirit thrives.

JOHN LOVE JR., class of 1980

The end-of-school buzzer sounds, and West Charlotte High Schools students emerge into the early-summer heat. Clusters form as they wait for buses and for rides, cell phones in hands, muted conversations broken now and then by laughter. A handful of girls teases a tall boy standing in their midst; another boy, eyes on the giggling group, leans down to wipe a fleck of dirt from the white leather of his two-tone sneakers. A stone lion, mane swept back from an impassive face, presides over the scene. A lion has been West Charlottes mascot since the school opened its doors in 1938, a time when the banking mecca of Charlotte, North Carolina, was a midsized textile center, and ambitious African Americans from across the region flocked to the segregated neighborhoods on the citys west side in search of jobs and opportunity.

The history of West Charlotte High School tells a dramatic story of triumph and struggle. During its first three decades, it served the African American families who built Charlottes west side neighborhoods. Despite the constraints of Jim Crow segregation, it gave shape to a striving communitys ambitions, becoming a space in which a corps of skilled and dedicated teachers groomed young people to rise higher and go farther than their parents ever could. In the 1970s, when Charlotte embarked on a court-ordered school busing plan that would make its schools the most desegregated in the nation, West Charlotte emerged as the new systems celebrated flagship, embodying a multiracial determination to move beyond the inequalities of segregation, and to educate black and white students for life in an increasingly prosperous city.

But as the twentieth century neared its close, and a new court order eliminated race-based busing, it became clear that Charlottes celebrated economic growth had left many neighborhoods behind. This was especially true on the west side, which had been battered by urban renewal, highway construction, suburbanization, and a set of policies and practices that discouraged investment in historically black neighborhoods across the nation. Charlotte schools resegregated along lines of class as well as race, and West Charlotte became the citys poorest, least stable, and most academically troubled high school. For the first time in its long, distinguished history, its shortcomings seemed to outnumber its achievements.

Within that history lies a profoundly American story of education, community, democracy, and race. In a nation where success and failure are deemed to stem from individual merits or shortcomings, schools have become a centerpiece of democratic promise, cast as places where aspiring students can acquire the skills and knowledge to rise above their station and realize their dreams. In reality, however, this promise has often been denied. Schools have been tightly enmeshed in the societies around them, routinely designed to prepare specific groups of students for designated social roles, whether picking cotton, cleaning houses, tending textile mill looms, or directing state affairs. The separate and decidedly unequal schools of the Jim Crow South were a flagrant example of deliberately stunted possibilitiesone reason why the long legal campaign against de jure segregation began with schools.