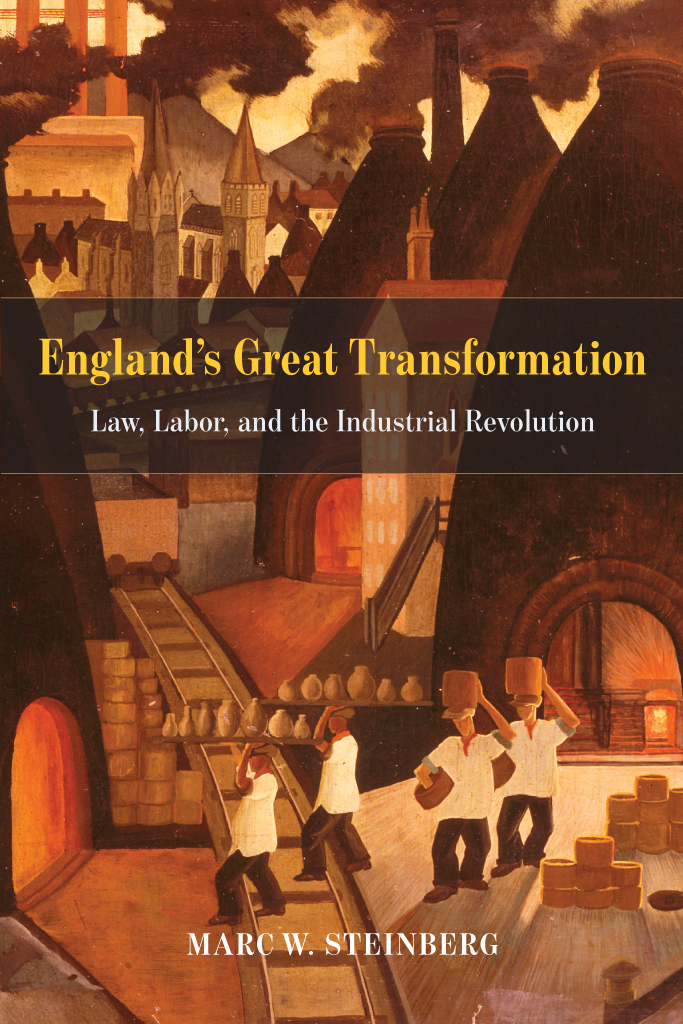

Marc W. Steinberg - Englands Great Transformation

Here you can read online Marc W. Steinberg - Englands Great Transformation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: University of Chicago Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Englands Great Transformation

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Englands Great Transformation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Englands Great Transformation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Englands Great Transformation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Englands Great Transformation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MARC W. STEINBERG

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

MARC W. STEINBERG is professor of sociology at Smith College.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-32981-9 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-32995-6 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-33001-3 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226330013.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steinberg, Marc W. (Marc William), 1956 author.

Englands great transformation : law, labor, and the Industrial Revolution / Marc W. Steinberg.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-32981-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-32995-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-33001-3 (e-book) 1. Industrial relationsEnglandHistory19th century. 2. Industrial relationsEnglandCase studies. 3. Labor laws and legislationEnglandHistory19th century. 4. Industrial revolutionEngland. I. Title.

HD 8390. S 795 2016

331.0942'09034dc23

2015024879

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Charles Tilly, who patiently taught me the fine arts and big problems of historical sociology, and who always encouraged me to forge my own path,

and

David Spring who brought me into the world of English history

A couple decades ago I was busily at work writing a dissertation that would eventually see the light of day as my first book, Fighting Words. My investigations ultimately led to an argument concerning how class struggle was expressed, conditioned, and channeled through discourse. Back then I was deeply steeped in British Marxist history of class formation during the Industrial Revolution. My friend and, at the time, mentor, Peggy Somers, politely suggested that I was more than steeped; I displayed a certain inebriation in sometimes purple prose concerning the heroic efforts of workers battling against the dark forces of capitalism. It offered exhilaration, but she was correct, of course, as was my adviser Charles Tilly, who pushed me to consider the ways in which my analyses moved beyond the classic and dominant account of Thompsons The Making of the English Working Class.

Abandoning the prose was one matter, but focusing on particular forms of class struggle was another. British Marxist historians offered a remarkably rich account of how workers struggled against emergent forms of capitalist subjugation through machine breaking and property destruction, anonymous threatening letters, emergent forms of strikes, underground radical politics, and other captivating forms of dramatic resistance. They also highlighted the ways in which capitalists turned to state repression and violence to meet and defeat these workers.

Indeed, one of the two case studies that made up the dissertation and subsequent book had all these trappings. In my analysis of the struggles of the cotton spinners of Ashton-under-Lyne and surrounding towns in Lancashire I found huge strikes, attacks on strike breakers, assaults on mills, and even an assassination of a mill owners son. Cotton manufacturers turned to the local magistrates who, with the support of Westminster, sent in troops to quell what they saw as the start of a possible rebellion. This was class warfare!

And then I turned to my second case, the silk weavers of the Spitalfields district of London, and matters got complicated. Yes, the silk weavers, in their attempts to resist the dismantling of the legal protections of their trade and the precipitous debasement of their wages and community status turned to some pretty dramatic collective actions. They held mass demonstrations in front of Parliament in an unsuccessful effort to prevent the repeal of laws that had provided them with a modicum of material security for a half century. In the face of dramatic cuts in the piece rates paid by the large masters that dominated the trade, they responded with readily recognizable forms of resistance. Weavers engaged in a large-scale strike action in which many sealed their looms with wax, demonstrating that they had not and would not work on the materials already in production until their masters relented. Weavers who refused to participate were furtively visited at night and their work was slashed into worthlessness. And yes, the London police were called upon to hunt down the perpetrators of this destruction.

As I pored over the daily magistrates court reports to find prosecutions of weavers who had committed silk cutting, I noticed that the silk masters regularly engaged in an activity to control and discipline weavers that was nowhere on the class struggle roadmap that I had constructed. I began to notice cases of silk masters prosecuting weavers for neglect of work for not finishing their assignments on time. Paging through the daily records I found dozens of such cases. Sometimes masters seemed to rely on the law to break strikes, forcing weavers back to work under threat of prosecution; at other times they simply used the law to force weavers who had taken in work to bring their task to completion. Poking around I learned that the statutes on which they relied fit under the category of the Master and Servant Acts and that the offenses being prosecuted were defined by the law as criminal. This seemed both an oddity and a puzzle. It was an ongoing class struggle without all of the heat and hoopla of public contention that were this graduate students romanticized reading of the making of the English working class. And where strikes and property destruction I documented were episodic and often dramatic, this class struggle was more a continuous and quiet grind. I read a contemporary treatise or two on labor laws, developed a basic understanding of the Master and Servant Acts, and moved on, since this was outside the boundaries of my focus on discourse and working-class collective action.

But the questions from this encounter with the court reports dogged me, and eventually I returned to role of the law on class conflict, developing the current project that is this book. My attention turned to mid-Victorian England because that is when annual parliamentary reports on the number of prosecutions under master and servant law first became available. As I was developing my project several historiansmost especially Douglas Hay and Paul Craven, Robert J. Steinfeld and Christopher Frankwere publishing signal studies on the uses of master and servant law in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England that oriented and sharpened my focus.

As a student of Chuck Tilly I took it as my broadest purpose to offer an analysis of processes of structured inequality through time. In this sense I ask the same question he did in Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons: How can we improve our understanding of large-scale structures and processes that were transforming the world of the nineteenth century and those transforming our world? (1984, 2). That is in part why I return to mid-Victorian England and the Industrial Revolution. In writing about European revolutions Tilly remarked that the British case was a much-thumbed manual for their avoidance (1993, 104). In many respects the British industrial revolution became too much-thumbed, as historians and social scientists lefts their prints all over its pages in the search for the manual for development. My following analysis takes the mid-Victorian case as no such manual. Instead, I hope I provide a lens on durable structures of exploitation endured by groups of working people in factories, workshops, and at sea in this historical moment.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Englands Great Transformation»

Look at similar books to Englands Great Transformation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Englands Great Transformation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.