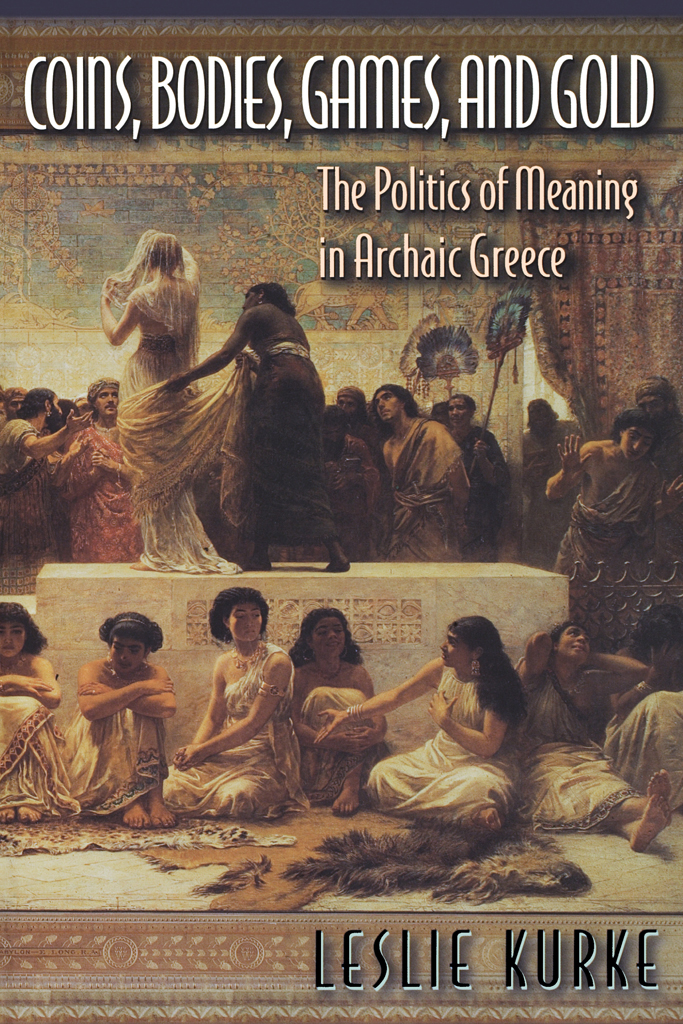

Leslie Kurke - Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold

Here you can read online Leslie Kurke - Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Princeton UP, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton UP

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

COINS, BODIES, GAMES, AND GOLD

COINS, BODIES, GAMES, AND GOLD

THE POLITICS OF MEANING IN ARCHAIC GREECE

Leslie Kurke

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1999 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kurke, Leslie.

Coins, bodies, games, and gold : the politics of meaning in

archaic Greece / Leslie Kurke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-01731-X (cl. : alk. paper). ISBN 0-691-00736-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. GreeceAntiquities. 2. GreeceCivilizationTo 146 B.C. 3. Meaning (Psychology)Greece. 4. Coins, GreekGreeceHistory. 5. GreeceSocial conditionsTo 146 B.C. I. Title.

DF222.2.K87 1999

938dc21 99-12205

http://pup.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-0-691-22332-2

R0

For Andrew

Illustrations

Preface

I STARTED OUT to write a book about the invention of coinage as the cause of a conceptual revolution in archaic Greece, but the more I worked on the topic, the more it seemed coinage was not a cause but a symptom of a complex shiftone site of contestation within an ongoing political struggle. And the more I looked at coinage, the more I was led to other things: the imagery of metals, stories about tyrants, prostitutes, counterfeiting, and games. Hence this is a hard book to characterize. It is much concerned with Herodotus, but it is not a book about Herodotus; it considers the invention and early use of coinage in the Greek world, but it is not really a book about coinage either. It might best be described as a study of some discourses, symbols, and practices through which competing ideologies struggle to imprint the world in archaic and classical Greece. For long before elitist and egalitarian ideologies emerge into the clear light of political rhetoric and political theory in fourth-century Greece, they exist and contest each other in an "incorporated" statein the stories people tell, the songs they sing, the games they play, and the coins they use.

The nature of the evidence imposes severe restrictions on such an inquiry: for any period of antiquity, we possess only 5 to 10 percent of the original literary and artistic production, while all that we do possess (at least of the literary remains) is the product of an elite of birth, wealth, and status. This makes it nearly impossible to write for Greek antiquity the history (or ethnography) of the "ordinary man" to which de Certeau aspires. Still, I believe there is much more evidence of ideological conflict traceable in our texts than is generally acknowledgedin the rifts and fissures left by the conflict of competing positions. There are two reasons for this. First, I follow Ian Morris in seeing the struggle of elitist and egalitarian positions as an intra-elite opposition, so that we can find both positions explicitly espoused in the literary remains. Second, the peculiar conditions of production and reception in archaic and classical Greece require a reading that focuses on the receiving audience and its positionality as much as on the "author." For in this period, all poetry and also (I believe), Herodotus's prose, were composed for public performance and embedded in clearly defined ritual or social contexts. Thus the sites for literary performance ranged from the closed group of the elite symposium to the entire city assembled for the staging of tragedy and comedy. Each different performance site required a different compact of author and audience, a different agreement on the values and models espoused. But also, given their social centrality, these performance texts did not simply reflect their audience's values but in some measure also constituted audience and values in turn. It is this double action within representation (including material representations like games and coins) that I try to capture and describe.

For the notion of "incorporated" practices, see Bourdieu 1977, 1990; for the relatively late appearance of explicit political theory in Greece, see Loraux 1986: 173-80, 202-20, Ober 1989: 38.

For this notion, cf. de Certeau 1984: 22.

Morris 1996.

Acknowledgments

I HAVE BEEN THINKING ABOUT and writing this book for a very long time and have incurred many debts along the way. It is a pleasure to record them here. Juliet Fleming, Tom Habinek, Ian Morris, and Seth Schwartz helped me enormously with conversation, ideas, and reactions as I was first conceptualizing the project, while Deborah Boedeker, Anne Carson, Page duBois, Kathy McCarthy, and Josh Ober provided invaluable support (both moral and intellectual) at its end. There are also a few people whose encouragement, intellectual stimulation, and engagement with the work have been so constant and so sustaining that this book could not have been written without them: they are Carol Dougherty, Mark Griffith, and Richard Neer. To them I owe the profoundest debt. Many others read some or all of the manuscript at various points and gave me valuable responses in spoken or written form: for that, thanks to Danielle Allen, Karen Bassi, Paul Cartledge, David Chamberlain, Kate Gilhuly, Robert Knapp, Donald Mastronarde, James Redfield, and Sitta von Reden. Needless to say, none of them agrees with all that I have argued here, but all of them have challenged me to enrich and complicate my thinking. I owe special thanks to Chris Howgego, Henry Kim, and Jack Kroll, who over the years shared their ideas and numismatic expertise on various issues and generously read parts of the manuscript. Even when they have disagreed with my interpretations, they have consistently encouraged me in my work.

I recently observed, in response to a query by a colleague, that this book could have been written only in Berkeleynot merely because of the financial support I have received from the University of California, though this has been substantial (two years of leave in 1993-94 and 1997-98, funded by a President's Research Fellowship in the Humanities and two Humanities Research Grants, as well as generous yearly research and RA funds), but also because Berkeley provides an extraordinarily vibrant intellectual community. For that, in addition to the colleagues and students I have already named, I would thank all the participants in my "Economies and Literature" Graduate Seminar (fall 96), who listened to and argued over many of the ideas presented here, and the members of my reading group, Katherine Bergeron, Tim Hampton, Celeste Langan, Michael Lucey, and Nancy Ruttenburg, who read and improved most of the manuscript-in-progress over the years. Thanks are also due to James Ker for his superb editorial work on the penultimate version of the manuscript; in the end, he was much more of an intellectual interlocutor than a research assistant. In addition, for help with various technical matters along the way, I owe thanks to my colleagues Crawford Greenewait Jr., Robert Knapp, Donald Mastronarde, and Ron Stroud. And, though I conceptualized and finished this book in Berkeley, I started it elsewhere; for hospitality during a leave year I spent in Austin and Cambridge, I'm grateful to Michael Gagarin and Simon Goldhill.

Brigitta van Rheinberg, Classics and History Editor at Princeton University Press, has been supportive and enthusiastic about the project from the time I first described it to her and has eased the passage from manuscript to book at every stage. Marta Steele proved an efficient and good-natured copy editor. William Fitzgerald drew my attention to Edwin Long's painting,

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold»

Look at similar books to Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.