SUSAN J. PEARSON

2021 Susan J. Pearson

Set in Minion by Copperline Book Services, Inc.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Jacket image: The standard birth certificate, issued by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Names: Pearson, Susan J., author.

Title: The birth certificate : an American history / Susan J. Pearson.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021865 | ISBN 9781469665689 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469665702 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Birth certificatesUnited StatesHistory. | Registers of births, etc.United StatesHistory. | CitizenshipDocumentationUnited StatesHistory.

INTRODUCTION

THE LIFE OF A DOCUMENT

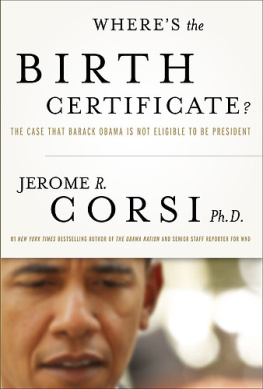

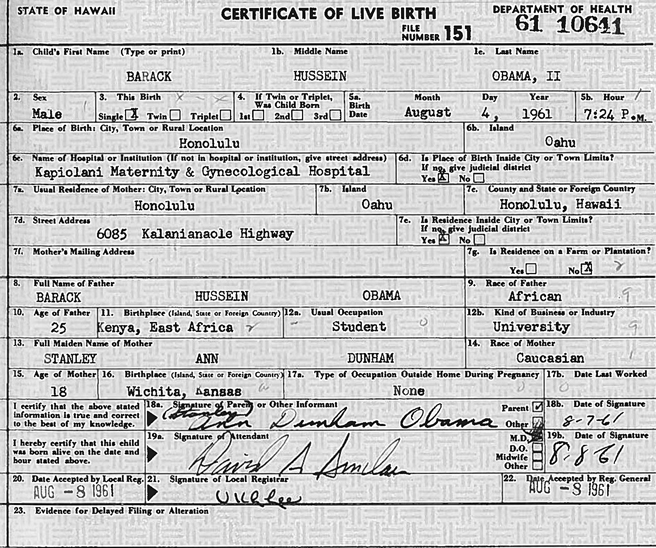

Many years into researching and writing this book, I received a coffee mug from a friend. On one side was emblazoned the birth certificate of President Barack Obama; on the other side, a photograph of a smiling Obama, captioned Made in the USA. The mug, of course, was an artifact of the birther controversy ginned up by a civilian Donald Trump to cast doubt on Obamas citizenship and therefore on his ability to serve as president. As many analysts have noted, birtherism was clearly racist, and President Trumps subsequent treatment of nonwhite, female members of Congresstelling them to go back whence they came despite their U.S. citizenshipdemonstrated his basic assumption that the United States is a white mans country. Yet few analysts have noted the powerful political work that Obamas birth certificate () was summoned to do. Emblazoned on my mug, reprinted in countless publications, and broadcast across the television news, the bureaucratic form mobilized its boxes, its official paper, and its mute ordinariness to supply facts in the face of falsehoods, to offer up the epistemological foundation for citizenship and belonging.

Figure 0.1. The birth certificate of Barack Hussein Obama

President Obamas birth certificate was repeatedly scrutinized and published, making clear the often-unacknowledged political work that identity documents perform. Source: State of Hawaii.

That Obamas birth certificate was summoned to do this work owes not simply to the Fourteenth Amendment and its guarantee of birthright citizenship. Instead, it owes to a function that birth certificates have been made to perform only in the recent past: proof of identity. When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868 very few Americans would have had birth certificates to prove that they had been born on U.S. soil. The U.S. government did not yet issue standardized passports, and the Department of State did not ask applicants for a birth certificate to prove their citizenship. Indeed, in 1868 even those few Americans who had had their births registered would have been unlikely to ever use a certificate of birth to establish the facts about themselves: their name, place and date of birth, their parentage, their nativity. Instead, if questioned about any of these, they would have relied on the testimony of relatives, friends, and neighbors or they would have adduced the family Bible or other personal papers.

President Obamas political advisors hoped that the release of his birth certificate would settle the matter of his citizenship not because birth certificates are inherently citizenship papers but because in the preceding century and a half, a host of individuals, civic organizations, and governmental officials at all levels, from city and county to state and federal, had made them so. These men and women waged a long and iterative campaign that made birth registration universal in the United States and transformed birth certificates into trusted, authoritative identity documents. Today, nearly every baby born in the United States is registered, and birth certificates are the breeder documents that generate those that are in even more common usedrivers licenses, social security cards, and passports.

This book describes both sides of that story: how birth registration became universal and how birth certificates were transformed into portable identification long before any other forms of identification were routinized and standardized. Reformers from the 1830s through the 1950s convinced municipalities and states to adopt laws requiring registration at birth; they taught city clerks and state registrars to value human bookkeeping and to issue standardized forms; they convinced policy makers that birth registration could be a source of important public health data; they encouraged parents to value birth registration and to cherish the token of that act by pasting their babys certificate into a baby book or framing it on the wall; they pushed states to make birth certificates into proof of age for employment and old-age pensions or proof of race for access to marriage, schooling, and land; and they argued that, because birth certificates were made by disinterested state officials, these documents were more trustworthy than the testimony of neighbors and more reliable than dates scrawled into the family Bible.

We know that these campaigns were successful not simply because the contemporary United States has universal birth registration. Success is measured also by what it means to fail. Anyone without a registered birth, or without easy access to their birth certificate, is at a severe disadvantage. Indeed, birth registration is considered so fundamental to modern citizenship that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child names it as a fundamental human right. Birth registration affords children official, legal personhood: a name, a birth date (and therefore an age), a family, and a country. Birth registration makes a child known to a state, and a child who is known can be more easily protected from being forced to marry, soldier, or work underage; a child who is known belongs to a country and is entitled to its protections and entitlements. A child who is known can move freely and return to her country of origin. A child who is registered has legal parents who have legal obligations to her.

Across the world more than 290 million children (or about 45 percent) under the age of five do not officially exist. While most of those children live in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the undocumented are at a disadvantage no matter where they reside.

Birth registration does more than provide identification, however. It is also used to create aggregate data about children and their parents that can be used to construct population information and to guide programs of social welfare and public health. It allows a country to gather data about how many children are born annually, where they are born (what towns, cities, or regions), to whom (ethnic or racial groups, single or married mothers), and how (at home, in a hospital, vaginally or by cesarean). Today, birth certificates in the United States are used to record not only identity but also a variety of data about, for instance, prenatal care, maternal habits such as smoking, and whether the birth was covered by public, private, or no insurance. Medical journals are filled with studies that trace the relationship between birth registration and vaccination rates and that use birth registration data to compile infant mortality rates around the world, analyze gestational weights according to maternal age and prenatal care, and track induction of post-term births, to name a few. Indeed, when U.S. reformers began to promote improved birth registration in the 1830s and 1840s, they argued that so doing would provide better public health data and improve public policy.