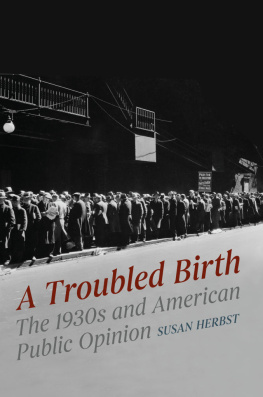

A Troubled Birth

Chicago Studies in American Politics

A series edited by Susan Herbst, Lawrence R. Jacobs, Adam J. Berinsky, and Frances Lee; Benjamin I. Page, editor emeritus

Also in the series:

Prisms of the People: Power and Organizing in Twenty-First-Century America

by Hahrie Han, Elizabeth McKenna, and Michelle Oyakawa

The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized Era

by James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee

Democracy Declined: The Failed Politics of Consumer Financial Protection

by Mallory E. SoRelle

Race to the Bottom: How Racial Appeals Work in American Politics

by LaFleur Stephens-Dougan

Americas Inequality Trap

by Nathan J. Kelly

Good Enough for Government Work: The Public Reputation Crisis in America (And What We Can Do to Fix It)

by Amy E. Lerman

Who Wants to Run? How the Devaluing of Political Office Drives Polarization

by Andrew B. Hall

From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and the Political Environment Shape Religious Identity

by Michele F. Margolis

The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized

by Daniel J. Hopkins

Legacies of Losing in American Politics

by Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow

Legislative Style

by William Bernhard and Tracy Sulkin

Why Parties Matter: Political Competition and Democracy in the American South

by John H. Aldrich and John D. Griffin

Neither Liberal nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public

by Donald R. Kinder and Nathan P. Kalmoe

A Troubled Birth

The 1930s and American Public Opinion

Susan Herbst

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

On the cover: Men lining up for a cheap meal during the 1930s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81291-5 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81310-3 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81307-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226813073.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Herbst, Susan, author.

Title: A troubled birth : the 1930s and American public opinion /

Susan Herbst.

Other titles: Chicago studies in American politics.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Series:

Chicago studies in American politics | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012759 | ISBN 9780226812915 (cloth) |

ISBN 9780226813103 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226813073 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Public opinionUnited States. | United States

Politics and government19291933. | United StatesPolitics and government19331945.

Classification: LCC HN90.P8 H495 2021 | DDC 303.3/80973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012759

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of my brilliant and wildly imaginative mentor,

James R. Beniger. I got lucky.

Contents

Birth of a Public

Towering over Presidents and State governors, over Congress and State legislatures, over conventions and the vast machinery of party, public opinion stands out, in the United States, as the great source of power, the master of servants who tremble before it.

James Bryce, The American Commonwealth, 1888

Rich fellas come up an they die, an their kids aint no good, an they die out. But we keep a comin. Were the people that live. Cant nobody wipe us out. Cant nobody lick us. Well go on forever, Pa.

Ma Joad, The Grapes of Wrath, 1940

No one predicted the near-simultaneous appearance of a global health crisis, the resulting crash of economies, a surge in protests across the world over race discrimination, the refusal of a sitting president to accept the outcome of a legitimate national election, and a violent invasion of the Capitol building by insurrectionists inspired by their president. Yet in the years before these profoundly impactful events of 2020 and 2021, we had plenty of other surprises in our politics: the rise of the Tea Party and other novel forms of partisan rage, the election of our first African American president and its varied impacts, flamboyant rejection of empirical reality by cable news figures, a rapid proliferation of conspiracy theories, and the fierce, cult-like populist uprising fueled by a wealthy celebrity real estate developer. We failed to predict Donald Trumps astoundingly rapid domination of a major political party, his reshaping of the culture inside the US Senate, his tyrannical war against so many truths, and his frightening interventions in the workings of institutions we had typically accepted as supporting the public goodthe Justice Department, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Postal Service. Also not predicted was the emergence of a novel incivility in public discourseits uniquely coarse tone and its loose adherence to facts, both shaped by the linguistic peculiarities of Twitter. All of these current phenomena matter immensely, so academics interested in politics have rushed to press with questions, concerns, and a frantic search for explanations. Pundits and journalists have been vital, trying to parse the events, albeit with varying degrees of thoughtfulness and sincerity. And these phenomena loom large for every citizen as well; they undergird most all daily media content that we watch, read, retweet, and talk about. The bottom line: We live in a period characterized by partisan polarization, cynicism about our institutions, and a generally mean-spirited ruckus so extraordinarily loud that folks from all walks of life fear each other and question the very possibility of democracy.

The precursors to these phenomenaattitudes, trends, cultural artifacts such as television programs, and conspiratorial websiteswere all there in public view, but clearly they were not properly studied. My own scholarly community is partly to blame, and our only excuse is that it was all complex, fluid, and bigger than we thought.

This is a book about how we might do better, not through sophisticated statistical models or more huge attitude surveys, although both are always welcome tools. Anything is worth a try, given what is typically at stake for a nation. Instead, this book grapples with how the public and public opinionas concepts that undergird this nation and make it vulnerable to antidemocratic movementscame to be. I argue, through the lenses of social and intellectual history, why these fundamental concepts led us into an iron cage of assumptions, biases, and expectations that make us passive, vulnerable to authoritarian behavior of leaders, anti-intellectual, and generally resistant to what should be our citizenly duties. The ways we developed our notions of the public and its sentiments long ago came back to haunt us, and in 2021 we need to understand and face it all.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).