THE WORKING CLASS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Editorial Advisors

James R. Barrett, Thavolia Glymph,

Julie Greene, William P. Jones,

Alice Kessler-Harris, and Nelson Lichtenstein

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

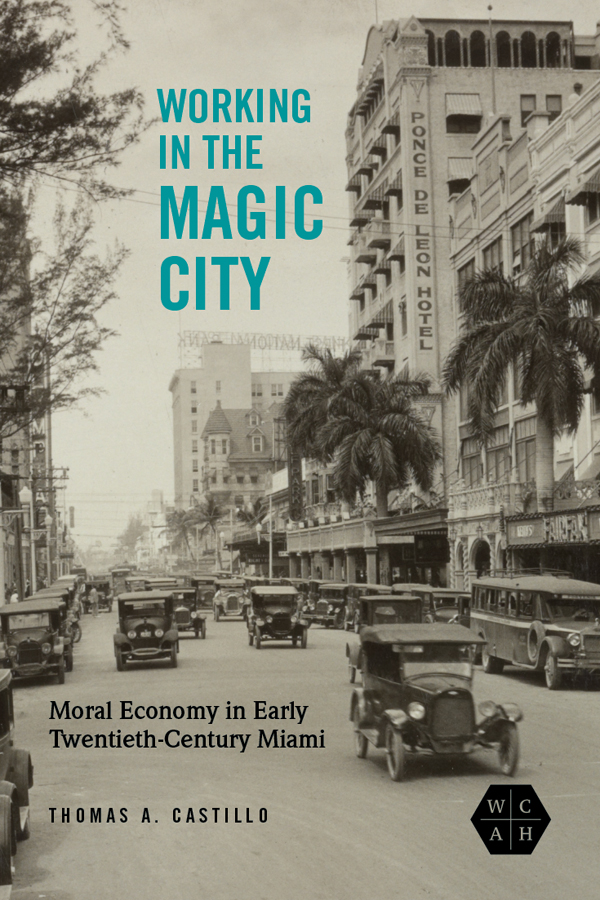

WORKING IN THE MAGIC CITY

Moral Economy in Early Twentieth-Century Miami

THOMAS A. CASTILLO

2022 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Castillo, Thomas A., 1971 author.

Title: Working in the magic city : moral economy in early twentieth-century Miami / Thomas A. Castillo.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2022] | Series: The working class in American history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021055205 (print) | LCCN 2021055206 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252044458 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252086533 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252053450 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Working classFloridaMiamiHistory20th century. | Social conflictFloridaMiamiHistory20th century. | Service industries workersFloridaMiamiHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HD8085.M5293 C37 2022 (print) | LCC HD8085.M5293 (ebook) | DDC 305.5/62759381dc23/eng/20211201

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021055205

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021055206

Preface

In many ways, this book began when I was twelve years old. Past-due mortgage payments and the demands of a five-child household kept my parents economically anxious. One significant moment was when my dad was left in the lurch when his only employee, Roberto, quit his one-man-run Castillo Painting Company. My father earned a living painting people's houses in early 1980s Greater Miami. It was barely a small business. His effort to join the local painting union yielded inconsistent work, a function of the whittling of construction union power over the years. The anxiety of getting enough work to pay the bills likely intensified my dad's lack of tact and rough nature, leading to a hostile work environment. Roberto certainly had cause to leave, but my dad was a struggling worker, too, desperately seeking to survive America's increasingly antiunion environment. It is unclear to me whether my dad asked or whether I volunteered, but I ended up working for him that summer and the next (and sometimes over weekends during the school year). I continued working for my dad on and off for the next several years.

It was during the period between 1979 and 1984 that a declension narrative emerged in my family about our recent past. Amid the economic struggle, my dad would express deep regret for making the decision not to follow a General Motors parts factory that was moving to Bensalem, Pennsylvania, at the end of 1978. GM was consolidating three plants, including Englewood, New Jersey, where my father had started working in 1966. Because my dad was a United Automobile Workers (UAW) unionist, the workers in the plant were offered funds to relocate and retain their jobs. Instead, my father decided to go south in 1978 and create a life for his family in south Florida. According to my mother, he continued to dream that he would return to Colombia and transplant his American children. He long wished to return to his home country especially after having been successful in establishing a family. I did not know this fact until my mother told me about his intentions sometime after his death in 2005.

In any case, our consistent economic woes forced my dad to hold two jobs at times and my mother to begin her own work life in retail. That did not prevent us, during at least one period, from having to go on food stamps. Food-stamp coupons looked like Monopoly money back then, and it carried enormous stigma. It broke my parents hearts.

In many ways, my youth ended when I was twelve years old, and I have ever since been shaped by the hard lessons of forty-eight- to fifty-hour workweeks. We were often restricted from picking up the telephone because of the threat of the bill collectors calling. All we ever could afford were used cars, which required us to develop our olfactory and auditory senses so as to detect the seemingly inevitable mechanical problems of our vehicles. Too often needed home and car repairs were postponed, or my dad did the best he could to correct immediate problems. My mom worked her magic to make ends meet with creative budgeting or cooking that helped spread meager quantities while also soon getting work in retail. My mom's entrance into the workforce really hurt my dad, and his conservative value that his wife should be focusing her energy on keeping up the home. Of course, maintaining the home was a full-time job and childcare was a costly non-alternative.

For my dad, dental care was usually done by an unlicensed immigrant who had practiced back in their home country; I do not recall more than one or two visits to the dentist in my youth and certainly nearly none during my teenage years or twenties. My older brother and sisters were forced to find work as soon as they were legally able to (at sixteen years where we lived at the time) in order to mitigate our collective struggle. The day after my sixteenth birthday, I filled out an application to work at Bojangles Chicken, where my siblings had worked years before me. Our ever-present anxiety, although rooted in the economic, permeated all other realms of my and my family's existence in Greater Miami.

In conversations around the kitchen table during the 1980s, my dad would wax nostalgic about how well we had had it in New Jersey, how he had made it in the United States as a Colombian immigrant without ever finishing high school. This success was defined by his luck in meeting my mom, an immigrant from El Salvador, on a San Francisco trolley in the early 1960s. Labor union history, though, was critical to the actualization of this American Dream story. His memories of Englewood were imbued with narratives of dignity and respect. His eyes would glitter with such life about how he did not have to take any shit from the foreman, especially if he looked at you in a funny way because all he had to do was go to the shop steward and lodge a complaint. My dad was remembering how he was treated with dignity, earned a living wage, had benefits, and was not human capital to be used and tossed when no longer needed. The UAW got GM to pay for his relocation, if he so chose. That sort of articulated respect demonstrated my father's value as a human being and as a worker and the benefits of collective action. I am not sure whether he knew any labor historyprobably not much. But those rights he had had as a worker in Englewood were the result of many hard-fought battles and much pain and suffering. He stood on the shoulders of many workers before him.

Nor could he have known how those victories were tragically being reversed. What he ended up getting in the 1980s and after were hokey Ronald Reagan platitudes about Morning in America and a faith that he was a member of the middle class. No doubt, his memories of Englewood dignity shaped his perceptions. The dissonance between reality and fantasy crystalized into a deepseated alienation. Since life is lived in the here and now, few have the luxury of engaging deeper structural dynamics. The rhythms of work and play take too much time. An onslaught designed to discipline worker unwillingness to accept neoliberal precepts had just began. That story has to await another book. This one reaches back to one place and time that happens to be a location where I once lived (and still have loving family and friends residing) and whose class history I just happened to research. It is perhaps unsurprising that I found many of the roots of the Reagan era precarity simply by chance.