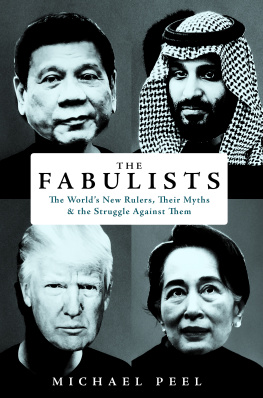

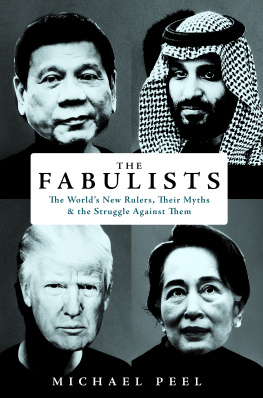

Peel - Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them

Here you can read online Peel - Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: LightningSource, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Peel: author's other books

Who wrote Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Sam, Lorin and Owen

Contents

Introduction: Civilisation Story

Not far outside Brussels, there stands a group of ponds where Belgiums king once kept a human zoo. The well-manicured grounds of the neoclassical Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren are a favourite place for Sunday family outings these days, but the tranquillity hides a dark history. In 1897, seven Congolese people died from exposure suffered while living in makeshift villages set on four sites in the area. Leopold II had created the ersatz settlement as an attraction for the crowds who came to an international exhibition he commissioned to show his wealth and power to the world. Photos of the time show what the 267 Congolese shipped in for the monarchs pleasure were forced to do. Some stand in front of huts, dressed in traditional clothes designed for the tropics. Others ply the lake waters in canoes.

In mid-2018, the site of the villages bore no record of the fatalities, which were mentioned only briefly on the museums website. They were a tiny fraction of the mass casualties that Leopolds twenty-three-year rule from his little sliver of Europe inflicted on the vast territory of what he named the Congo Free State. As many as ten million people died as the monarchs agents executed a reign of terror and forced labour. The kings rule sucked the wealth from the areas large resources of rubber into the royal coffers in Brussels. Leopolds forces murdered, maimed and drove workers to death by exhaustion, while many other Congolese fled their homes and died from starvation or disease.

Today, despite all that is known about the horrendous abuses that took place under his rule, Leopold still retains his place in the pantheon of Belgiums former rulers. A massive portrait of his thick-bearded figure is hung in a high-ceilinged room in the countrys mission to the EU, where the government held briefings for journalists. The room itself was known internally after Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of independent Congo until he was murdered in 1961 with Belgian complicity. Which, as statements go, is a bit like honouring Nelson Mandela and then hanging a picture of Cecil Rhodes on the wall.

Nevertheless, changing times have brought some concessions from the Belgian state over Leopolds legacy. The Africa museum shut its doors in 2013 for a long overdue revamp. The renovation was a response to concerns that, as the museums website understatedly put it, the exhibition was outdated and not very critical of the colonial image. Among the artefacts under debate was a golden statue that stood near the entrance, of an African boy hanging on to the robes of a European missionary. Its inscription read: Belgium brings civilization to Congo.

An old story, for long expedient, had finally become unsustainable. As the museums online blurb put it, again with some delicacy, a new scenography was urgently required. A fresh version of history its truth still to be tested was to be substituted in its place.

After more than two decades as a journalist, in four different global regions, the clash between myth and reality I felt beside the Tervuren museums ponds seemed all too familiar. Pathologies of denial and delusion appeared the norm. They loomed large, both in the way leaders presented themselves to their peoples and the world, and in a narrative the West told about itself and the rest of humanity. They buttressed autocratic figures in both dictatorships and democracies who were profiting from the growing rip tide of unpredictability, anxiety and anger that coursed through so many societies.

In the previous nine years, Id witnessed many events that had caused widespread shock. In the Middle East, I travelled from Libya to the Gulf and saw the early hopes of the so-called Arab Spring dissolve into war and repression. In Asia, I charted the end of a royal era in Thailand, the singular durability of another in Brunei, and the role foreigners and international financial institutions played in a vast Malaysian corruption scandal that crossed continents. I returned to a Europe gripped by authoritarian revivalism and ever harsher methods for dealing with migrants whose desperate conditions I had seen at their starting points in southern Turkey and West Africa. For years, I worked to the background drumbeats of Syrias long war, Brexit and President Donald Trumps America First campaign: all events whose significance appears to me still in important respects misrepresented and misunderstood.

This book is the story of one journey to puzzle through the modern age of fabulism, in countries at the centre of world attention and others little thought about by outsiders. The events I witnessed from Bangkok to Bucharest often alarmed me; they didnt surprise me so much. They seemed linked by a style that stretched across cultures, continents and political traditions. All too often, they felt like the predictable, even inevitable, outcomes of the fabrications, wishful thinking and complacency that seem to grip our world ever more tightly.

Some commentators flourish statistics that proclaim humanity is richer and life better than ever before. It often didnt feel that way to me, for all the many moments of grace and inspiration provided by the people I met. I saw precarity wherever I turned, from individuals struggles to planetary pollution.

Together, the geographically scattered stories in this book highlight crises of legitimacy of one sort or another. They speak of the stuttering credibility of rulers, systems and ideas, many of them born in or backed by the West. They expose fundamental fallacies about the spread of liberalism, the potential for benevolence in dictatorship, and the nature of conflict and history itself.

The more I travelled, the more intrigued I was by how national myth-making was both distinctive and in some way archetypal. Every narrative involved winning and consolidating power, either for individuals or more often an elite group. Sometimes, outsiders would be told a very different story from that spun to citizens. Chinas President Xi Jinping, his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, and Narendra Modi, Indias premier, all drew heavily on contentious ideas about their countries backstories and place in the wider world.

The techniques are old but The Fabulists argues that the events of the past decade or so have shown that myth-busting has never been more urgent. We are running out of time to deal with existential problems ranging from environmental destruction to sharing the wealth of the world more equitably. What is alarming now is not so much a shortage of truth sometimes a slippery or shaded ideal but the abandonment of the quest for it, especially by so many of our leaders. On fundamental points such as making our own societies fairer, ensuring people around the world can live with dignity, or curbing climate change, the strategy is often to avoid the difficulties or pretend they can be easily solved by crude crackdowns on already victimised groups. At times it seems as if, in some deep sense, we have given up on problems that seem too great to solve, even though the only way to tackle them is to stare them in the face.

The Fabulists in this book are those who push dangerous fantasies about the world around us. Some of these myth-makers are leaders who present themselves as national saviours or are promoted as such by backers at home and abroad. Those featured here include the hardman Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, the supposedly reformist Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, and the once internationally lauded human rights icon Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar. None turned out to be all they seemed.

Autocrats through the ages have spun stories to reinforce their power, but a feature of the modern age of myth is the way this approach has spread to supposed democrats. Elected politicians have become ever more brazen in planting dubious or outright false narratives that have become internalised at home and even convinced observers abroad. If all else fails, these popularly validated leaders simply shrug off legitimate questions and rely on their propaganda to tide them through. Jair Bolsonaro won Brazils presidency in 2018 on an authoritarian hard right agenda, after making outrageous statements such as suggesting the countrys former military dictatorship should have killed more dissidents.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them»

Look at similar books to Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fabulists : The Worlds New Rulers, Their Myths and the Struggle Against Them and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.