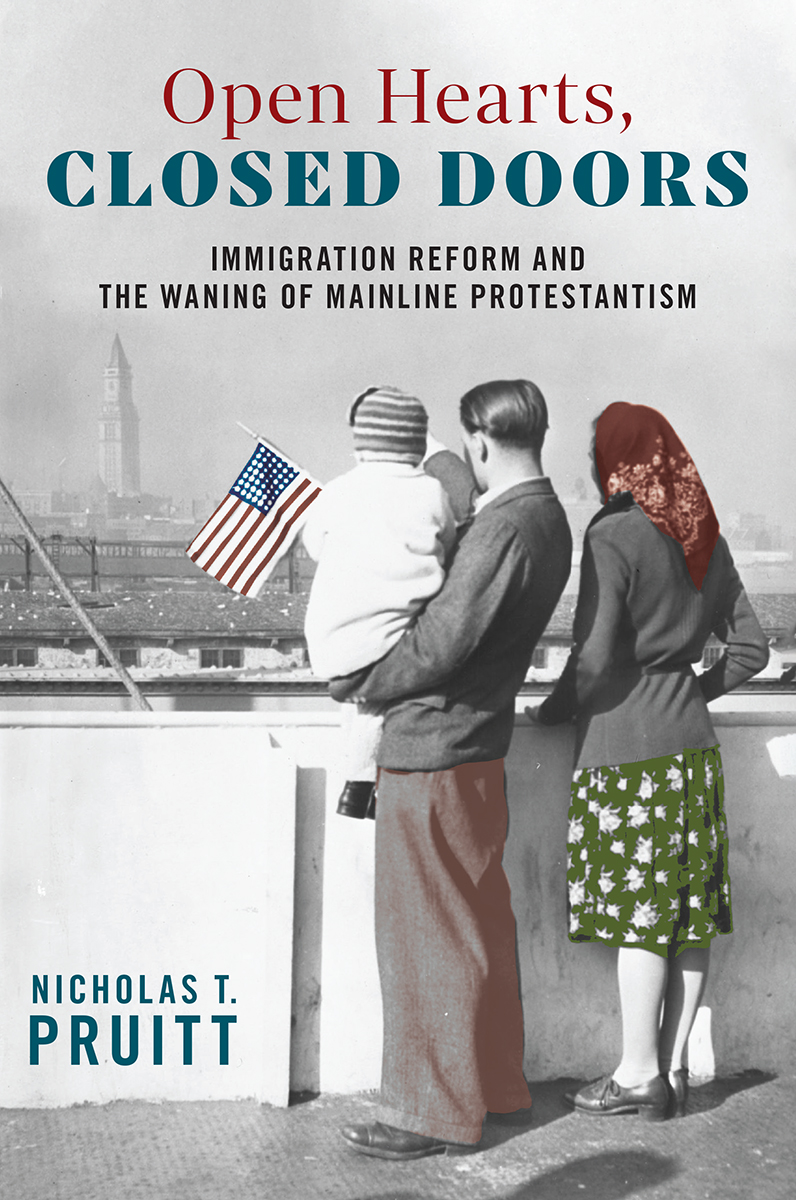

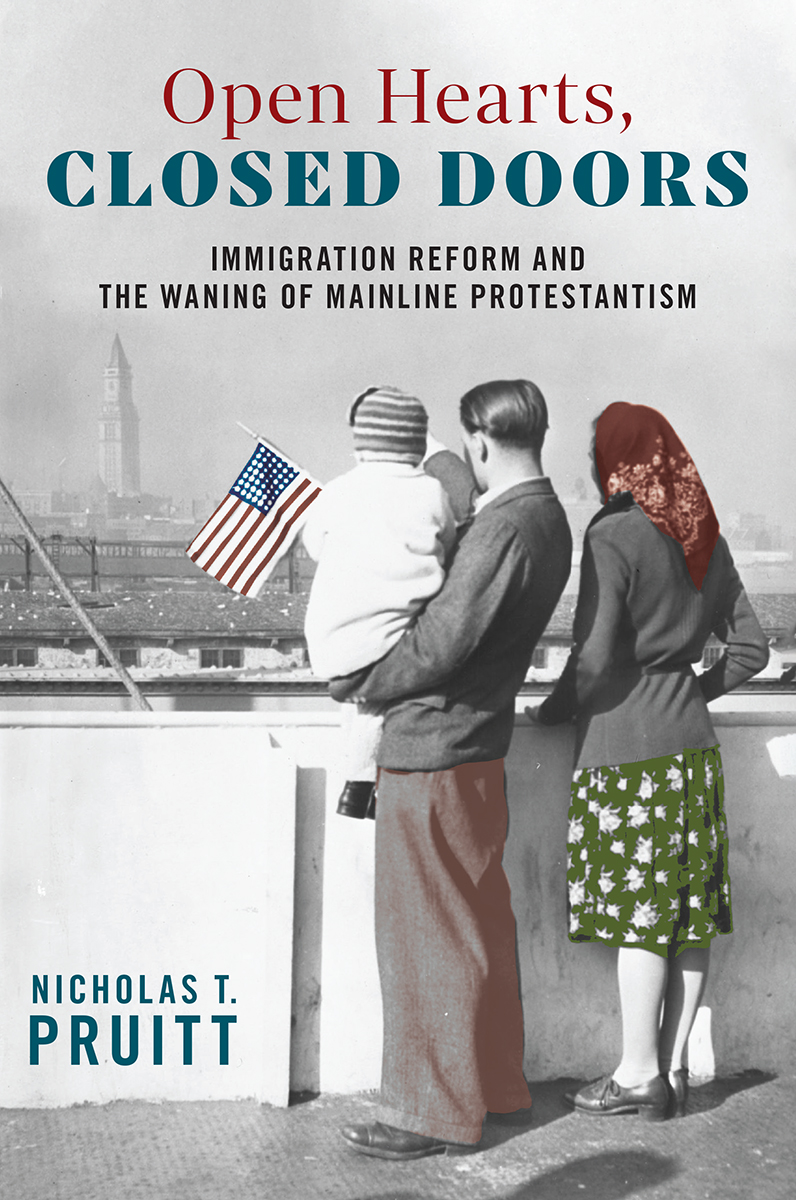

Open Hearts, Closed Doors

Open Hearts, Closed Doors

Immigration Reform and the Waning of Mainline Protestantism

Nicholas T. Pruitt

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2021 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pruitt, Nicholas T., author.

Title: Open hearts, closed doors : immigration reform and the waning of mainline protestantism / Nicholas T. Pruitt.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020039541 (print) | LCCN 2020039542 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479803545 (hardback) | ISBN 9781479803576 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479803569 (ebook other)

Subjects: LCSH : Protestant churchesHistory20th century. | Emigration and immigrationReligious aspectsProtestant churchesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC BX4817 .P78 2021 (print) | LCC BX4817 (ebook) | DDC 261.8/3809045dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020039541

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020039542

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To Barry Hankins

Mentor, Wordsmith, and Friend

Contents

ABCAmerican Baptist Convention

ABHMSAmerican Baptist Home Mission Society

ABHSAmerican Baptist Historical Society, Atlanta, Georgia

AECArchives of the Episcopal Church, Austin, Texas

AMAAmerican Missionary Association

BGCTBaptist General Convention of Texas

CCCCongregational Christian Churches

CCUSCongregational Churches of the United States

CHMSCongregational Home Missionary Society

CLACongregational Library and Archives, Boston, Massachusetts

CWHMCouncil of Women for Home Missions

CWSChurch World Service

FCCFederal Council of the Churches of Christ in America

HMCHome Missions Council

MECMethodist Episcopal Church

MECSMethodist Episcopal Church, South

NBCNorthern Baptist Convention

NCCNational Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA

PCUSAPresbyterian Church in the United States of America

PECProtestant Episcopal Church

PHSPresbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

SBCSouthern Baptist Convention

SBHLASouthern Baptist Historical Library and Archives, Nashville, Tennessee

UMAHCUnited Methodist Archives and History CenterGeneral Commission on Archives and History, Madison, New Jersey

UMCUnited Methodist Church

UPCUSAUnited Presbyterian Church in the United States of America

WABHMSWomans American Baptist Home Mission Society

But the world has suddenly become very small. Space has wondrously shrunk, and we are face to face in a closely intertwined and increasingly interdependent life. Isolation is no longer possible. A new era is upon us. The question for us all is whether this is to be a glorious era of brotherhood and good-will, an era of interchange of our best spiritual treasures and material achievements, or an era of enmity, aggression and strife.

Sidney L. Gulick, Adventuring in Brotherhood among Orientals in America

At the outset of the twentieth century, white Protestants still held a tight grasp on the cultural and social resources of the United States. Public school classrooms began each day with largely Protestant prayer, local stores closed on Sundays, national political leaders touted the centrality of Christian ideals to American identity, and an expanding overseas empire aimed to extend the reach of Christian civilization. For many Americans, such religious aspirations blended seamlessly with American cultural norms of personal enterprise, a shared English language, and democratic principles. This bold Protestant orientation simply would not last.

As the twenty-first century unfolds, Protestants still hold a disproportionate amount of power, but schools no longer expect prayer of their students and it is more common to witness a mosque or Hindu temple along the highway. Even long-standing Protestant denominations have surrendered much of their power to more recent evangelical groups and coalitions. When the 116th US Congress convened in 2019, while Protestants still claimed a majority of the body, 163 Catholic, 34 Jewish, ten Mormon, five Orthodox Christian, three Hindu, three Muslim, and two Buddhist members of Congress reflected a more apparent diversity. No matter how one interprets these changes, the social and cultural landscape of the United States by the early twenty-first century is much more diverse than it was a century earlier.

This coming momentous change, however, was not evident to the Protestant figures and politicians who gathered in 1961 at a consultation to discuss immigration policy. Religious leaders representing most mainline Protestant denominations met with key policymakers in Washington, DC for two days to discuss immigration reform. Attendees believed the nations immigration policy during the last four decades had enforced forms of racial discrimination that favored some nationalities over others. These liberal Protestants joined a chorus of voices at the time calling for the dismantling of the national origins system, thus allowing for more diverse groups of people to enter the country. Despite the pushback they would receive from their more conservative constituents, those in attendance were convinced that the nation could maintain a Christian identity while still tolerating the cultural diversity that accompanied immigration. Many in attendance also believed that the Cold War demanded liberal reform in order to distance the United States from the godless totalitarianism practiced in the Soviet Union. The themes of Protestant relief and Cold War concerns all converged in an endorsement the delegates received while at the 1961 conference. Consultations such as this focus attention upon an issue that is important to both our international standing and our national self-respect, declared President John F. Kennedy in a statement sent to the gathering. You who assume the daily burden of guiding the oppressed and the orphaned people of the world to productive and satisfying lives under the banner of freedom deserve our thanks.

Four years later, the Immigration and Nationality Act overturned in large part a restrictive immigration system put in place 40 years earlier that discriminated on the basis of race and national origins. This watershed moment helped to unsettle the white Protestant hegemony which had held sway for most of the nations history. What was once a nation whose leaders were steeped in Anglo-Protestant culture slowly came to accept forms of multiculturalism and provide opportunities for other ethnic, racial, and religious groups to participate in American political and social institutions, though much work remains. This book delineates the ways in which mainline Protestants in the United States from 1924 to 1965 facilitated and helped to define such pluralism as they responded to immigrants and refugees through home missions and political lobbying. During these four decades, Protestants contributed to the national debate over immigration policy; yet their positions would have unintended consequences. Largely overlooked, mainline Protestant leaders joined the drive for midcentury immigration reform, and in the process paved the way for a more plural nation. Mainline Protestant denominations tried to balance a limited form of pluralism and respect for cultural diversity with the conviction that America should be a Protestant nation centered on biblical tenets and church attendance; in short, they came to a pluralistic bargain. In so doing, they contributed to their own decline as cultural gatekeepers and aided in immigration reform that allowed for a cultural revolution as non-Western immigration changed the cultural and religious landscape of the nation.

Next page