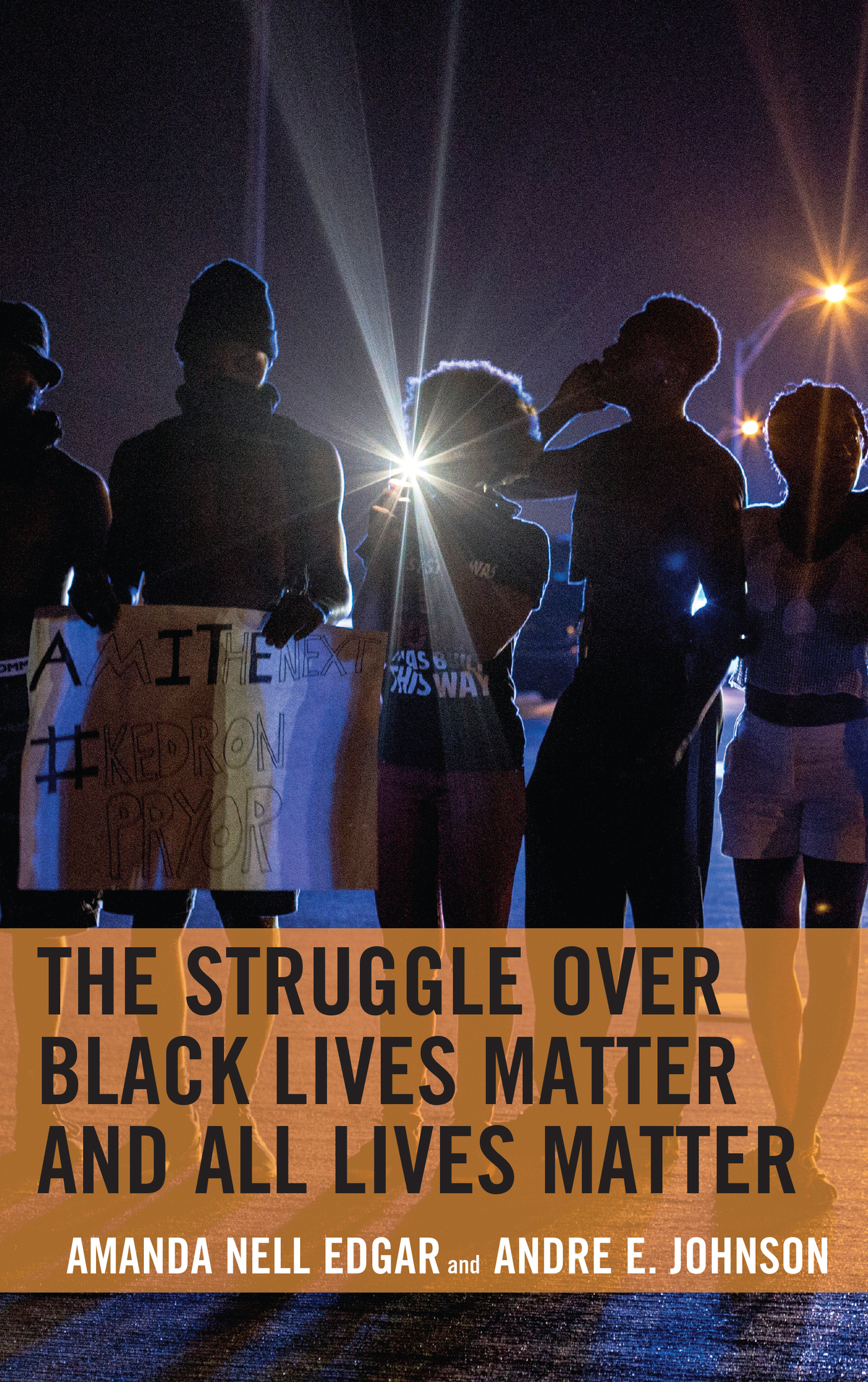

The Struggle over Black Lives

Matter and All Lives Matter

Rhetoric, Race, and Religion

Series Editor: Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis

This series will provide space for emerging, junior, or senior scholars engaged in research that studies rhetoric from a race or religion perspective. This will include studies contributing to our understanding of how rhetoric helps shape race and/or religion and how race and/or religion shapes rhetoric. In this series, scholars seek to examine phenomenon from either a historical or contemporary perspective. Moreover, we are interested in how race and religion discourse function rhetorically.

Recent Titles in This Series

The Struggle over Black Lives Matter and All Lives Matter, By Amanda Nell Edgar and Andre E. Johnson

Desegregation and the Rhetorical Fight for African American Citizenship Rights, By Sally F. Paulson

Contemporary Christian Culture: Messages, Missions, and Dilemmas, Edited by

Omotayo Banjo Adesagba and Kesha Morant Williams

The Motif of Hope in African-American Preaching during Slavery and the PostCivil War Era, By Wayne E. Croft, Sr.

The Womanist Preacher: Proclaiming Womanist Rhetoric from the Pulpit, By Kimberly P. Johnson

Women Bishops and Rhetorics of Shalom: A Whole Peace, By Leland G. Spencer

What Movies Teach about Race: Exceptionalism, Erasure, and Entitlement, By Roslyn M. Satchel

The Struggle over Black Lives

Matter and All Lives Matter

By Amanda Nell Edgar and Andre E. Johnson

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL

Copyright 2018 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4985-7205-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-7206-4 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

We dedicate this book to the many activists who stand in the rich

tradition of protest trying to make this country and world a better place.

Acknowledgments

Like social justice organizing itself, writing a book about the participants in a dynamic social movement like Black Lives Matter and its countermovement in #AllLivesMatter demands investment from a lot of people. We argue in this book that a movement is its people, and we owe the ideas in this book to the people who supported them, encouraged them, and shared them with us. First and most, we thank the participants who engaged with us and each other openly and in good faith. The perspectives given freely by movement and countermovement affiliates were gifts, and we were honored to spend the time and community with those whose views are represented in this book.

The task of gathering participants together was greatly aided by the support of Daphene McFerren and the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis. Without your generous support, this book would not exist. We also thank the Department of Communication at the University of Memphis, particularly Sandy Sarkela and Craig Stewart, for the financial and intellectual support necessary to complete this project. The top notch work our research assistants contributed to this project made it feasible; thank you to Kelly Ford, Bradly Knox, Alice Reid, and Cameron Brown for your work in support of this project. Our departmental writing group, The Juniors, kept us accountable: many thanks to Christi Moss, Michael Steudeman, Sachiko Terui, Lori Stallings, and David Goodman.

We are grateful for Nicolette Amstutzs work as our editor, and the anonymous reviewers who offered quality feedback both on the full manuscript and through various conferences to which we submitted along the way. Early versions of this work were presented at NCA, SSCA, RSA, and SCoR. Feedback at these venues was instrumental in shaping the ideas in this book, and we are particularly grateful to Lisa Corrigan and conference respondents for offering substantive and generative feedback in these presentations.

On a personal note, Amanda would like to thank Aaron Dechant for his unwavering belief in this project and to shout out to all of the family and friends who have patiently listened to her pontificate over the politics and (mis)framings of BLM and #ALM for the past three and a half years: Melissa Click, Jamie Kern, Holly Holladay, Sara Trask, Mallory Raugewitz, Mom, Dad, Andi, Milo, Raptor, Anekin, Kate, and Roxie. She is also so grateful to Andre Johnson for sharing his wisdom, unmatched work ethic, and friendship with her.

Andre would like to thank his wife and partner, Lisa, for her insight, wisdom, and activism. Also, he would like to thank his Gifts of Life Ministries church family for allowing him to write, research, protest, and still serve as pastor. Finally, he would like to thank Amanda Nell Edgar for sharing her vision and inviting him to join her in researching BLM and #ALM. He is a much better scholar by serving as her research partner and co-author of this book.

Chapter Introduction

A Movement from the Margins

In the weeks and months following the murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin at the hands of neighborhood watch vigilante George Zimmerman, social media was awash with posts both demanding justice and blaming the victim for his own death. Alongside these raw emotional reactions to Martins murder and Zimmermans subsequent acquittal, hashtags like #Justice4Trayvon and #HoodiesUp demonstrated the power of Black Twitter to rally around injustice and quickly spread the word about anti-Black violence through social media. This cultural moment also demonstrated the tendency for Black organizing to be met with examples of the same anti-Blackness activists seek to combat. As Charlton McIlwain, Deen Freelon, and Meredith Clark write in their 2016 report, social media users supporting Zimmerman and suggesting Martin deserved to die for his threatening appearance added noise to the online conversation.

The volume and variety of posts surrounding Zimmermans trial is perhaps the reason the first Black Lives Matter (hereafter BLM) Facebook post and subsequent tweet went largely unnoticed. However, when another teenager, Mike Brown, was gunned down by white police officer Darren Wilson in the St. Louis suburb where he lived, social justice Twitter was ready. This time, BLM was not only noticed, but instrumental in helping those in Ferguson to spread the word about what was happening on the ground. Then as the grand jury deliberated on whether to indict Wilson, and when their decision not to seek further justice for Brown was released, the hashtag became a massive phenomenon. As McIlwain, Freelon, and Clark note, the BLM hashtag had only been used forty-eight times prior to the month Brown was killed. That month, the hashtag was used fifty-two thousand times, increasing to ten thousand posts in the first twenty hours following the announcement that Wilson would not be indicted for Browns murder. These discourses quickly proliferated, growing into a tangle of ideas difficult to discern from any single standpoint.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.