Contents

Guide

Page List

STUDENT VOICE

100 Argument Essays by Teens

on Issues That Matter to Them

An Anthology from

The New York Times

Learning Network

KATHERINE SCHULTEN

For my mother, who taught me that the best afternoons are spent

on the couch with a book.

And for my students at Edward R. Murrow High School, who gave

me the ten happiest years of my career.

Contents

Appendix A:

The Rubric and Rules for the NYTLN Student Editorial Contest

Appendix B:

Covid-19 and the Teen Response: Three Essays from Our Spring 2020 Contest

This book would not exist if Michael Gonchar, my fellow Learning Network editor, hadnt come up with the idea for running a student editorial contest in the first place. It was his vision for how the contest could work that has made it a hit with teachers since 2014. Over the years we have switched rolesfirst I was his boss, and now he is minebut regardless of our titles, thinking about The Learning Network together has always been a wonderful, creative collaboration. Thank you, Michael, for being the best work partner I can imagine.

Student Voice would also not exist if Jane Bornemeier, editor of New York Times Special Sections, hadnt agreed to run some of these essays in print in 2018, where Norton education editor Carol Collins first read them and suggested to us they become a book. Thank you, Jane, for partnering with The Learning Network to spotlight the work of teens and teachers, and thank you to Special Sections deputy editor Jill Agostino and art director Corinne Myller for making it so fun and rewarding to create those pages together.

Carol Collins didnt just spot the potential for this book, she also guided it from start to finish. Carol, thank you for your brilliance in shaping what began as a fairly unwieldy project, and for your thoughtfulness about every tiny step along the way. Im grateful to the entire team at W. W. Norton for believing in Student Voice and making it and Raising Student Voice, the Teachers Companion, work so well together. Thank you to Mariah Eppes, who so ably shepherded it through multiple drafts, to Laura Goldin, for her expert legal counsel, to Katelyn MacKenzie, who managed the books production, to Anna Reich, who facilitated the cover design, to Irene Vartanoff, for her excellent copyediting, and Jamie Vincent, who assisted with permissions and all of the other logistical details.

I also owe a debt to several more people at The New York Times, especially Alex Ward, who was Editorial Director of Book Development when Carol proposed the idea, and whose kindness and entertaining knowledge of Times book-history helped me believe I could do this. Thank you also to Nicholas Kristof, who has always generously said yes to Learning Network invitations, and whose golden advice on opinion-writing is woven throughout the Teachers Companion. Thank you to Peter Catapano, Caroline Que, Brian Rideout, and Lee Riffaterre who helped smooth the way for these books, and met my nervous questions and concerns with expert guidance. And thank you to The Times itself, both for inventing The Learning Network in 1998 and for continuing to support it despite the many rocky years for the news industry since.

But most of all, thank you to the students and teachers who come to our site each spring and take part in our Student Editorial Contest. As a former teacher (and student!) myself, I know how much work went into every piece here, as well as into the thousands of others we receive annually. It is an honor and a joy to be an audience for them.

Finally, thank you to my family. To my parents, Carey and Judith Schulten, who set the best example possible for how to be in this world. To my children, Nick and Madeline Dulchin, who Id rather hang around with than anyone. And, especially, to my husband, Mike Dulchin, who is the luckiest thing to have happened to me in a very lucky life.

What makes you mad?

What do you wish more people understood?

What would you like to see change?

The essays in this book offer 100 different answers to those questions, in the voices of 100 teenagers from around the world.

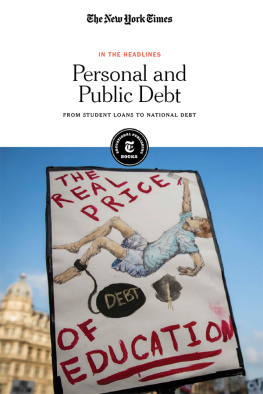

Some are heartbreaking and some are funny. Some ground their arguments in personal experience while others quote facts and statistics. Some take on issues you might expect, like gun violence and the environment, college admissions and #MeToo, while others raise topics you may never have considered, from bullying in gym class to the blessings of selfie culture.

No matter what they focus on, however, they all make us care. Thats one of our chief criteria for choosing winners in our annual New York Times Learning Network Student Editorial Contest each spring, and the essays in this book were selected from over 43,000 that have been submitted over the years.

The contest challenges teenagers to write about any issue they like and, in no more than 450 words, make a compelling case. We judgesLearning Network staff, volunteers from the Times Opinion section, and educators from around the countrychoose the pieces that do that best, then publish them online and, often, in print as well. We look for writing that gets our attention, introduces new ideas, engages us with voice and story, and convincingly backs its claims with rich and reliable evidence.

So if you are a student whose only association with the phrase persuasive essay is the formulaic writing you may have learned for standardized tests, these pieces can show you that theres more to the genre. If you assume this kind of essay always has to follow a set of ironclad rulessay, that you should never use the word I, or that it must be five paragraphs long, or that the thesis has to come at the end of the first paragraphthis book can offer you lessons in how, why, and when such rules might be broken, at least if your purpose is to interest a real audience.

In collecting these winning essays all in one place, we hope to offer you a set of mentor texts by kids your own age. Thanks to the work of people like Malala Yousafzai, Greta Thunberg, and the Parkland students, the concept of student voice is having a bit of a moment. Yet, as one student I interviewed pointed out, the opinion writing you study in school is still invariably by adultsby, like, 50-year-old white guys who have been doing this for their whole careers, as he put it. This book offers you the option of learning from fellow 1318-year-olds too, and placing their voices and concerns alongside those of professionals.

None of these essays is perfect, of course, but all of them have lessons to teach and craft moves you can borrow. Maybe youll start your piece with dialogue, the way Candice C. and Cheryl B. do in #27 , or maybe youll end it with a final line so powerful that it deserves its own paragraph, like that in #17 by Daina Kalnina. Perhaps Narain Dubeys essay ( #92 ) will show you how to write about a tragic personal experience and make a universal point. Or maybe Sarah Celestins piece ( #82 ) will convince you that good opinion writing doesnt always have to take on profound global issues, but can sometimes just be about pizza.