For Patricia Park (19332018)

A great wit, a great woman

Sit down a while,

And let us once again assail your ears

That are so fortified against our story

William Shakespeare, Hamlet , Act I, sc. i

Contents

First and foremost, my immense gratitude goes to the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia, which awarded me the Wolterstorff Postdoctoral Fellowship to write this book. I have been overwhelmed by the generosity shown to me there by director James Davison Hunter, Joe Davis, Josh Yates, Tony Lin, Jackson Lears and the staff, who have created a very special intellectual community. In terms of support, I also cannot sufficiently express my thanks to Paul and Sabina Marshall, Crispin and Nichola Odey, Ken and Fi Costa, John and Kara Kim, and our family away from home Guy and Susie Speers. In terms of research, my thanks are due to Tatiana Lozano, Rick Yoder and Henry Gumbel for their meticulous work as well as to the many people who kindly granted me interviews, read drafts and indulged my often embarrassingly basic questions, among them Denis Alexander, Peter Saunders, Trevor Stammers, Willis Jenkins, Christopher Kaczor, Samuel Matlack, Christian Guy, Johann Neem, John Kim, Jonathan Aitken, Danny Kruger, John Wyatt and Matt Ridley.

My own family have been with me through thick and thin on this project my parents, John and Eleanor, my parents-in-law, Andy and Judy, my children, Connie and Vera (born in Charlottesville while I was working on this book), my wonderful brother and sister-in-law, Marcus and Carey, and, above all, my extraordinary wife, Holly.

To Aristotle, or the school of Aristotle, is attributed the saying What we do through our friends we do, as it were, ourselves. My thinking has been shaped by countless conversations with brilliant colleagues who have been so generous with their time: in Charlottesville Rebecca Stangl, Charles Mathewes, Trenton Merricks, Nick Frank, Colin Bird, Greg Thomson and Matt Crawford; in London Jonny Gumbel, James Orr, Jonathan Tepper, Freddie Sayers, Maurice Glasman and remotely Tom Simpson, Charles Foster, Rich Nathan. I am also immensely grateful for my teachers Jacqueline Whitaker and Oliver ODonovan; for their encouragement at key junctures in the writing process to Susan Arellano, Rowan Williams and Xandra Bingley; and for poring over drafts to Aaron Kheriaty, Frank Curry and Micah Lott I have benefited so much from their philosophical acumen. I must thank Philippa Stroud and the Legatum Institute for their hospitality in the autumn of 2017. Finally, I am indebted to Jay Tolson, Talbot Brewer and Philip Lorish, without whose help I simply could not have written this book.

I dedicate this book to Patricia Park, my honorary grandmother, who was a brilliant woman, and a source of great inspiration and encouragement to me throughout my life. Before she died, she insisted I should not dedicate a book to her. She hasnt got her way on this one.

Ill put it bluntly. Politically, I dont like my options. Growing up in this giddy world b. 1981 Ive become increasingly dissatisfied with the alternatives on offer. Because there arent very many. Deep polarization has delivered unacceptable options.

And not just at a party-political level the dearth of boxes on the ballot paper. The real source of my frustration is the way every conceivable position on controversial moral issues has been bundled up into package deals that Im supposed to choose between. This clustering of causes across the political spectrum is the legacy the boomers bequeathed to us, and its got me all riled up.

My political identification is supposed to determine every view I take on the most fundamental questions I face. Say Im on the Left. Because of the way positions have been packaged, the way I vote means Im urged to press ACCEPT ALL to the terms and conditions of the whole deal: to sign off on every part of the platform. So, I passionately opposed the invasion of Iraq and defend affirmative action to the hilt. Am I simply to inherit an affirmative view of the legalization of drugs? Or maybe I am conservative. I worry about levels of immigration. I bemoan the rise of identity politics. Why am I then supposed to support greater sanctions on welfare for the unemployed?

It was a while before I was able to trace my dissatisfaction to its source this packaging of positions. In 2013 I moved to the US. I am British, but I also believe in America. I had lived there before as a child on the West Coast, in the Midwest for a time as a teenager, on the East Coast as a graduate student and had always been impressed and inspired by how sanguine were the people I met, how open. I liked their awareness of and investment in the American project itself. This time, though, the climate felt different. It may well have been because previously I had been inexcusably oblivious to the volatility of race relations. But now I was struck by the volatility of race relations. And I was overwhelmed by the extremity of polarization. I knew about this in theory. But now I saw for real what it looked like for people to be socially divided along political lines the faculty ostracizing the professor on the other side of the aisle; churches so engulfed by their division they ignored their raison dtre ; family members simply disliking each other; and dinner parties where there were no debates because no one from the opposite end of the political spectrum had been invited.

But what struck me wasnt just the partisanship, and its effects on how relationships fared and institutions functioned. It was the range of issues that had come to be enveloped by ideology. The sites of contestation werent just about matters of state about the federal budget or Irans nuclear programme. Thinking had become radically dichotomized about the most intimate quandaries, the most acute dilemmas, the weightiest of controversies birth and death, growing up and getting old, race and gender, sexuality, family, our obligations to those near and far, what I do with my body and what I do with my wallet. Morality had become thoroughly politicized. Two opposing political visions governed how to act, and how to think about how to act.

Then, the more I thought about the separating out into packages of so many positions on the most existential and important questions, the more I thought about the combinations. And the stranger they seemed.

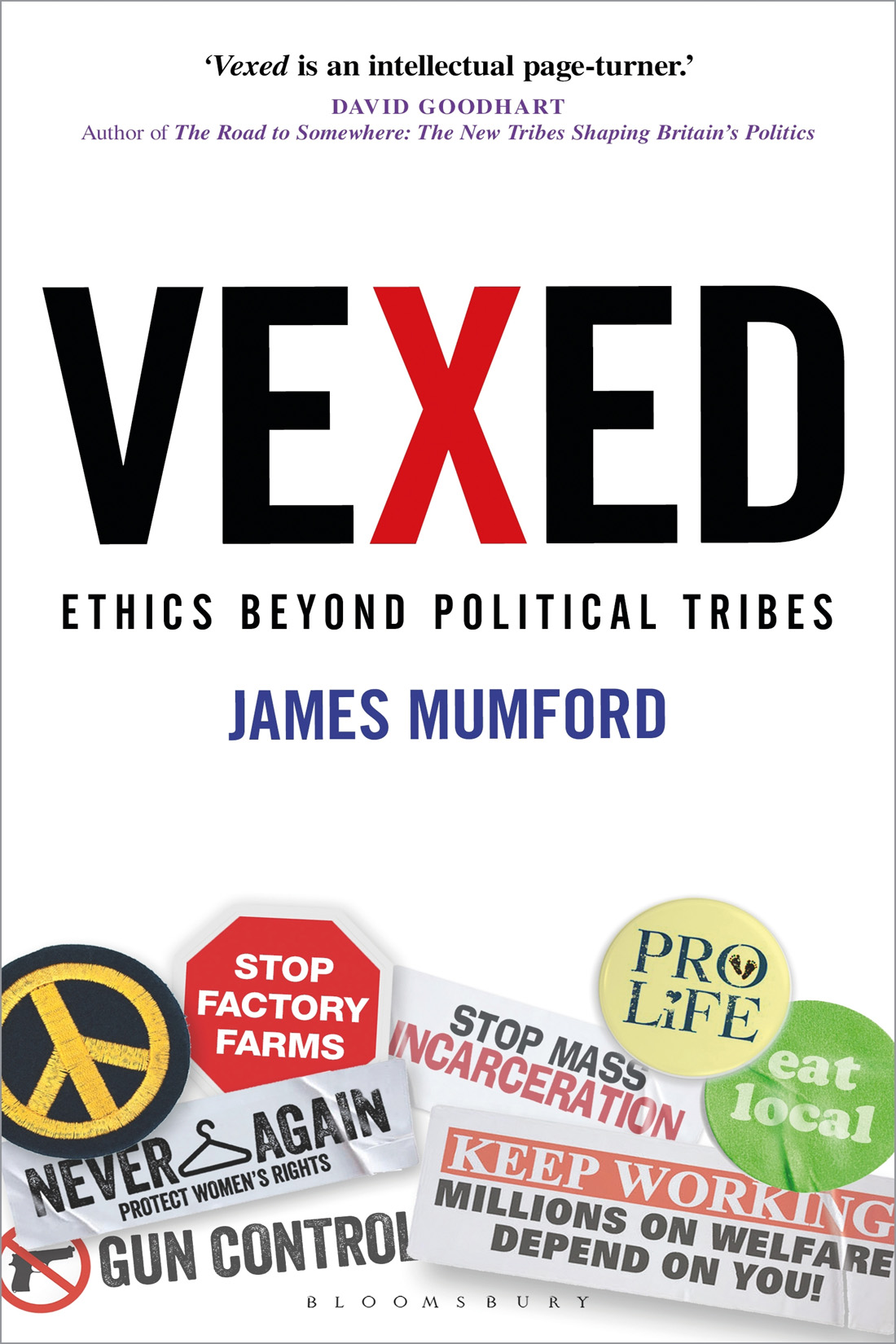

One of the things I was constantly riveted by in the US was the bumper sticker, one of the most familiar badges of identity. Those colourful if often weathered symbols, captions, emblems and jokes that drivers affix to their rear bumpers and other parts of their cars anatomy attest to far more than partisan affiliations and the onset of the latest election cycle. Alongside partisan convictions are environmental, social or cultural ones, blazing forth peoples highest ideals and principles for all the passing world to see. You wear your heart on the boot of your car.

But what is most revealing about these stickers is the company they keep on each individual car. You pull up at the traffic lights. On your right is a car juxtaposing Liberals Take and Spend. Conservatives Protect and Serve with Pro Guns. Pro God. Pro Life. On your left is a car displaying a rainbow flag alongside Buy Fresh Buy Local, No Nukes and Co-Exist. Those stances may be ideologically aligned. But do they imply each other? Why should being religious preclude buying fresh, local produce? Why should a dedication to diversity commit you to unilateral disarmament?