Contents

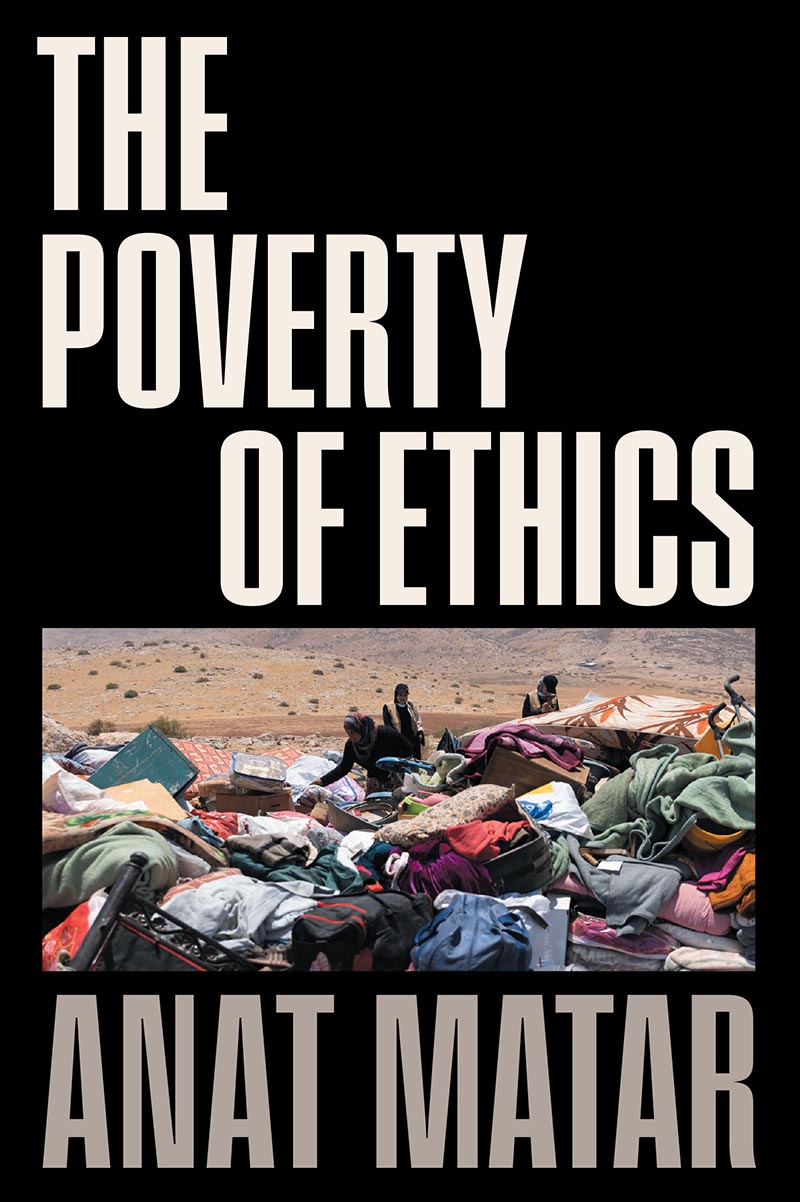

The Poverty of Ethics

The Poverty of Ethics

Anat Matar

First published by Verso 2022

First published in Hebrew as Al Dalut Hamussar,

Hakibbutz Hameuchad, Bnei Brak 2019

Anat Matar 2019, 2022

Translation Matan Kaminer 2022

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11217

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-592-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-595-7 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-594-0 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

For Amira

Contents

Which language is this book written in?

The answer is not as straightforward as it may seem. In Modernism and the Language of Philosophy (2006), I tried to tackle a question which had haunted me for years: after the Kantian Copernican Revolution, what could the status of philosophical propositions be, once the self-assured (or simply dogmatic) presumption of representing truths sub specie aeterni had to be forsaken? Modernist philosophers and writers portrayed in the present book by Anatole Frances fictional character Polyphilos adopted a view of language in which philosophical terms and propositions are but relics of an old philosophical hubris. My purpose in that previous book was to uncover pitfalls and blind spots in the modernist analysis itself, arguing for a more nuanced, postmodernist conception of language, one which problematizes and overcomes the rigid distinctions between different discursive realms in particular, those of everyday and philosophical language. As the present essay will clarify, paragons of this nuanced conception are the later Ludwig Wittgenstein, Valentin Voloshinov and Jacques Derrida. The main tenets of this book too are intimately linked to questions about language. These questions, however, are subsidiary to its principal topic. Nevertheless, they merit mention now, upon publication of an English translation, since I realize, at this juncture, that this version of the book is somewhat out of joint in two senses. And I recognize that both the ways in which it is strained are uncharacteristic of a philosophical work which essentially aims (as this book surely does!) to transcend the particularities of space and time.

So, space:

One evening, several years ago, I was sitting with an activist friend outside the Jaffa Theatre (A Stage for Arab Hebrew Culture) as the audience poured out of the small auditorium at the end of a play about Palestinian political prisoners. We were discussing the book I was writing the one youre about to read and I laid out its general plan.

But this is such a universal theme, Kobi said. Why write the book in Hebrew? Youll have a much larger readership if you write it in English, wont you?

Sure, I replied, and gestured towards the dozens of activists filling the theatre courtyard, but Im basically writing the book for these people!

This books theme, ideas and arguments are indeed universal, and may be of interest to anyone invested in leftist activism and thought. Yet I wanted to write the book in Hebrew for reasons that derive directly from its philosophical-political stance.

At some point, towards the end of the concluding chapter, I criticize Wittgenstein (a rare move for me). The complaint that I present against him there is directed towards a particular remark of his: The philosopher is not a citizen of any community of ideas. That is what makes him a philosopher. I believe that no line or body of thought let alone political thought occurs outside of a community. This is not to dismiss the crucial importance of an independent locus of hesitation vis--vis the often all-too-mechanical responses of the community of ideas on the left. Such a locus is vital to that community and to its (our) political struggles. Indeed, articulating and maintaining it is an important role which philosophers should play; but this role is always played within and in relation to their own political communities. Denying this is itself an aspect of a deeply entrenched political dogma.

One of the most important insights that we have inherited from Marx is, in my view, that philosophy can and should be a crucial component in the toolbox enabling our political struggles. Although it is often overlooked, this insight arises when we realize that philosophy, with its demystifying power, can and should dismantle dogmatic strongholds deeply entrenched beliefs, attitudes and conceptual frameworks which are uncritically taken to be obvious, to constitute our shared common sense. Philosophy can and should offer more than mere criticism, though, as significant as it may be; it should offer an alternative framework, a conceptual space in which a radical political motivation can develop.

This is what I aim to achieve in the present essay. It scrutinizes the system of sacred concepts and attitudes that form our ordinary view of the relationship between the moral, or ethical, and the political. I argue against the vision assigning the ethical conceptual precedence to the political and holding that, in one sense or another, we need an independent notion of morality to show leftist politics the way. The book advances an intricate argument whose conclusion is that neither abstract moral principles, aesthetic-ethical sensibilities nor the ethical demand emanating from an other, can be translated into the terms of political will, much less into direct political action. Indeed, it is my belief that an appeal to ethics as independent of political affiliation erases the true nature of political struggle. Political struggle, as I construe it in this essay, arises primarily out of our communal aspirations to liberation and opposition to oppression. Moral abstractions, which suppress such political presuppositions, end up serving as a faade for oppression of various kinds.

Back in the Jaffa Theatre courtyard, in that conversation with Kobi, I was articulating the significance I placed on services, consisting of ideas (and action), that I believed I could offer my own community. My philosophical analyses could help rip to shreds the moral rhetoric enabling and underpinning the code of ethics commissioned by and serving Israels army (and providing justifications for every atrocity it commits). Or mock the presumptuous text of Israels Rules of Ethics for Judges (and expose the fallacy of self-proclaimed judiciary independence, one that is agonizingly familiar to anyone who has faced the closed doors behind which the General Security Service requests administrative detentions, for instance). Or lay bare the presuppositions underlying liberal attacks of radicalism, and also show why our struggles are motivated by healthy self-interest and not by pity (and hence an accompanying sense of superiority).

The last point relates to another reason for my decision to write the book in Hebrew. This book is a self-assertion. Here I am, writing confidently in my own mother tongue, thinking through its conceptual framework, realizing its potential, richness and charm, refusing its marginalization. Such, I believe, is the stance from which political thought and action is taken. Everything else moral principles, ethical-aesthetic sensitivities and the distress of an other demanding our intervention follows and receives its interpretation, its sense, from this basic stance.